The Medieval Middle East in Video Games and Board Games

As historians of the Medieval Middle East, it is hard to ignore the large gap between the things we study and the way they are presented to and consumed by most of society. This blog post focuses on how the Medieval Middle East is represented in popular culture, specifically in games.

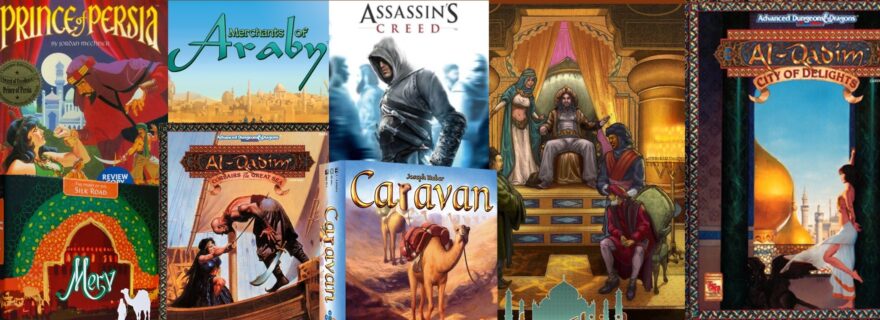

Arabic is one of the most prolific literary languages of the pre-modern world. The vast literature from the medieval period gives a varied window onto all aspects of life. I’ve been doing some research into this topic, and I’d suggest that most games drawing upon the Medieval Middle East (MME) can be fit into just four overlapping archetypes: the 1001 Nights; Bazaar trading; Desert life; and the Crusades. These themes often mix fantasy with history, and medieval aspects with modern elements.

The Source Material

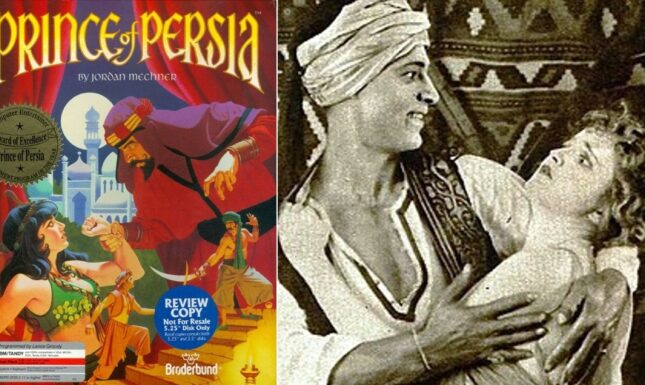

First, let’s acknowledge the obvious: a lot of the original source material for the MME in pop culture has long purveyed problematic racist stereotypes. The major sources feeding the Western imagination of the pre-modern Middle East carry with them a set of stereotypes that have then been constantly reproduced in one form or another. To name but a few examples: Tolkien’s Haradrim sided with Sauron; in H.P. Lovecraft’s nightmarish fantasy, the book of ghoulish black magic, The Necronomicon, was written by “the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred.” As for The Arabian Nights,(1001 Nights) it is a wonderful piece of literature, but by a process of cultural transmission, it has in Europe become conflated with 19th-century erotic fantasies about the sexual control of harem girls in tinselly bikinis (see images below). The Crusades are a little different. I’ll come to that.

Archetype 1: Arabian Nights

Fantasy is a big part of the way the Medieval Middle East is constructed. The fantasy of the Arabian Nights is perhaps the most common source material for Middle Eastern elements. Fantasy settings allow for a blurring of cultural lines between North African, Middle Eastern, and between Arab, Persian and Indian.

While games create a fantasy playground, cultural blurring allows consumers to ignore humanizing historical specificities, perpetuating old visions of an eternal Orient starting somewhere east of Vienna and blurring and mixing up until the borders of China.

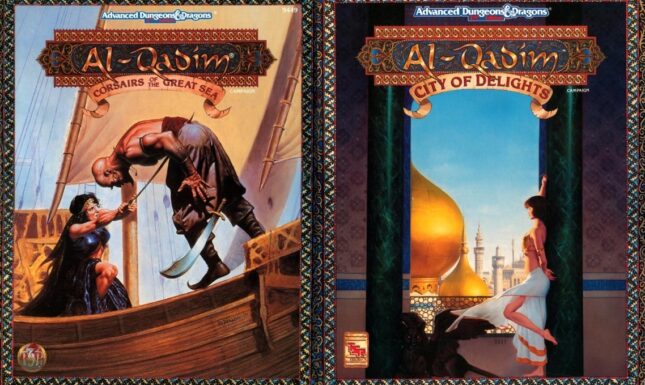

The Dungeons and Dragon’s setting of “al-Qadim”, published in 1992 combined aspects of historical and cultural research with these old stereotypes. (Interestingly for me, a historian from the University of Chicago, where I did my PhD, acted as historical consultant on this setting)

Archetype 2: Bazaar trading (and camels)

Different media and genres relate to slightly different archetypes. Modern boardgames often centre upon trading, and so it is no surprise that Middle East-themed games often have a trading component. However, as innocent as that often is, it can be linked to the old stereotype of the hooked-nose semite haggling in the souq. Some MME games emphasize dodgy-dealing and theft.

Positive images more often come in the closely-related Central Asian settings. For some reason, the idea of the “silk roads” connecting Europe to Central Asia, China and India seem to have more positive and historically-rooted connotations than do settings in the Middle East itself. The boardgame Merv has references to actual historical cities on Central Asian trade routes.

Archetype 3: Desert life

Many games draw inspiration from the desert, its inhabitants and the ways of life associated with it, and such settings often overlap with a trading theme. See for example Targi, a boardgame centred around North African Tuareg nomads controlling desert trade. Desert settings are not necessarily Medieval, but often depict a "timeless orient" in which it is difficult to see specifical historical markers. (You rarely see desert nomads in games equipped with that central pillar of modern nomadism: the pickup truck). The various Dune-themed boardgames depict the struggle over desert-derived natural resources, echoing mid-20th century geopolitics of oil as Frank Herbert's original novels did. Desert games also usually include a whole lot of camels.

Archetype 4: The Crusades

If a game aims at a genuine historical view of the Medieval Middle East, it will almost always be connected with the Crusades. Ironically, given their goal of establishing Christian hegemony in the Middle East, Crusade settings, through their romanticized literary receptions in Europe, arguably offer the most positive vision of the Medieval Middle East. Much of this probably harks back to the wild success, in the early 19th century of the Scottish writer Walter Scott’s revival of medieval European romances. In Scott’s stories, the Kurdish ruler of Syria, Saladin (Salāḥ al-Dīn), served as a model of chivalry, even as he stood in rivalry with the Christian knights who acted as Scott’s protagonists.

Saladin pops up everywhere, especially in strategy games like Sid Meier’s Civilization franchise and the Crusader Kings games. Occasionally you see other historical settings are explored in some marginal contexts, like the 2012 indie boardgame al-Rashid, which is set in the golden age of the Abbasid caliphate, and takes a more self-consciously historical approach to the reign of Hārūn al-Rashīd, who is the most famous historical figure to be mentioned in the Arabian Nights. (And note the frustrating return of the bikini in the image!)

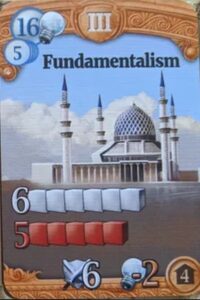

One of the frustrating aspects of the popular conception of the MME is that it is absurdly often seen as an intrinsically more religious place than Europe, with extra points in strategy games for ME leaders who capitalize on religion, like in the videogame Civilization VI. (I talk about this in another blog post here)

Game designers have difficulty, perhaps understandably, positioning Islam. Christianity and paganisms, by contrast are handled as neutral background or mythologized. Islam is usually avoided. An exception is the 2015 strategy game, Through the Ages: A New Story of Civilization in which a modern-seeming, or perhaps timeless Islam appears to offer players a military advantage through the “Fundamentalism” card. This idea, however, is clearly derived from the experiences of the 20th century, albeit might be imagined to relate to a pre-modern past.

The odd one out: Assassin’s Creed

The Assassin’s Creed franchise of videogames needs a whole separate treatment and I’m not going to do that here. The original games stem from the familiar setting of the Crusades, while giving agency to non-Western, non-Christian characters. The weirdest thing about them is that they take the Assassins, a derogatory name for a historical group, mythologized by both Middle Eastern and European polemicists and storytellers, and turns them into something entirely different. The word “Assassin”, derives from the Arabic “Ḥashīshiyyīn” (Hashish-users). It was a derogatory term used to attack a the Nizārī Ismailis denomination of Shiʿism, a group that still exists in the world today. In the game, this group is not merely fictionalized, but entirely deracinated, to become a kind of masonic fighting cult with a decidedly un-Islamic skeptical philosophy. This is the equivalent of a game suggesting that all Roman Catholics fly spaceships and can talk to aliens with their minds. In these games, then, the Assassins are taken out of their medieval historical context and made to be something modern and timeless, drawing upon both exoticism and mysticism of the past, while attempting to be an empty shell into which players can project their violent fantasies. This is compounded by the later releases in which Assassins have nothing to do with the Middle East or Islam: moving from Ptolemaic Egypt (AC: Origins) to Sengoku Japan (AC: Shadows) all the way to 19th Century London (AC: Syndicate). While AC1 is set during the Crusades, notably the player has to fight the European Crusaders, crucially repositioning the player’s identification. But identification with what? Certainly not with a real Middle Eastern or Islamic group.

For someone familiar with medieval Ismailism, Assassin’s Creed, then, is full of the most spectacular absurdities, but it is at least a solid attempt to reconstruct what the Medieval Middle East looked and felt like, particularly in its first installment. The latest step in this direction is the more recent installment of the franchise (2024), Assassin’s Creed: Mirage, which reconstructs 9th-century Baghdad at its height, and a nice free version of the world is available for students and those interested to walk around and interact with the Orientalist hodge-podge that is Ubisoft’s medieval Baghdad. https://www.ubisoft.com/mirage-medieval-baghdad/

Having played it a bit, however, I suspect that it is less carefully historical e.g. in its material culture than games set in Europe, and perhaps that has something to do with the consumption of history by the public: While there is a fanatical subculture of games enthusiasts (especially military games enthusiasts) who are obsessed with e.g. the reconstruction of the settings of Napoleonic battles, or the details of 19th century American train companies, public interest in historical details of the Middle East seems to be more limited, and so interest in historical details is also more limited.

Conclusion

Games are a way of putting yourself in someone else’s shoes, of modelling experiences that are distinct from your own. There are some improvements in the way the Middle East has been portrayed in recent years, with fewer actively racist stereotypes used, but the basic paradigms are hard to shift. Perhaps if scholars of the Medieval Middle East engaged more with games and gaming themselves, this would move the dial. And there are a couple of important steps in this direction: see for example, Glaire Anderson’s Digital Lab for Islamic Visual Culture & Collections at the University of Edinburgh, and The GamingIslam initiative at the University of Chicago https://www.youtube.com/@VideoGamingIslam both focused more on the “Islamic” than the “Middle Eastern” but commenting on the medieval Middle East.

© Edmund Hayes and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Edmund Hayes and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.