Setting the early medieval world on fire

Early medieval cremation burials have long been seen as the remains of non-Christian peoples. Recent research shows this narrative does not comfortably fit the archaeology of that period.

Northern Gaul, 5th century CE. The Roman legions pull back their forces from the northern provinces. What is left is a vast stretch of land that had already started to become more and more vulnerable to outside attacks from beyond the Empire’s borders. Now the last protective measures fall away, the Germanic incursions into the unprotected lands are more frequent than ever. As northern savages reign supreme, the ‘migration period’ begins.

This is the image the most people have of the start of the early middle ages (400/450-800 CE). The problem of that narrative is that it is based on historical sources that the 18th century scholar Gibbon formed into a dramatic story of the fall of the great Roman Empire. My discipline of archaeology was only used sparingly in these early narratives. And only ever as an illustration of the story that historical sources seemed to tell.

Thomas Cole’s Destruction, the fourth of a series of paintings on the Roman Empire. It depicts the sack of Rome, showing utter chaos as ‘civilisation’, as it is conceptualised by 19th century contemporaries, has fallen. This painting may be seen as illustrative of how people perceived the ‘dark’ middle ages that followed. Source: Wikicommons

Heathen traditions?

A common explanation for early medieval cremation burials places them in the dualism between Christian and non-Christian beliefs. The disappearance of cremation burials from the archaeological record in favour of inhumation burials is believed to coincide with the introduction of Christianity. Due to Christianity’s tendency to emphasise the importance of preserving the body, archaeologists who observed the change from cremation to inhumation readily associated the changing burial customs with the idea of a spreading Christian dogma. Cremations are believed to represent non-Christians, whereas the more common inhumation rite is often associated with Christian practices.

“Si quis corpus defuncti hominis secundum ritum paganorum flamma consumi fecerit et ossa eius ad cinerem redierit, capitae punietur”

"The one that gives the body of a deceased to the flames, as is the rite of heathens, so that their bones turn to ashes, shall be punishable by death."

-Translation from German transcript by Goetz 2013, 158.

This fragment from the lawcode Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae (782 CE) evokes a vivid picture about the early medieval cremation rite. From the 19th century onwards, this fragment of text lead scholars to associate cremation practices with unlawfulness and heathenism. When early medieval cremations were found archaeologically, they were most often interpreted as those of Germanic heathens. This interpretation was based on a text written 300 years after some of these burials were happening.

It is quite understandable, given the influence of Christianity’s on society at that time, that early scholars were compelled to interpret early medieval archaeology in the light of an upcoming Christianity.

However, there are several arguments against this reasoning. For example, the German scholar Masanz (2010) argues that the cremation rite was the most common method of burial in the Roman world, in which Christianity originated. If first century Christians could be cremated, why wouldn’t 5th, 6th and 7th century Christians be doing the same thing? This at least hints at the possibility of cremation and Christianity not being mutually exclusive, as has so often been suggested.

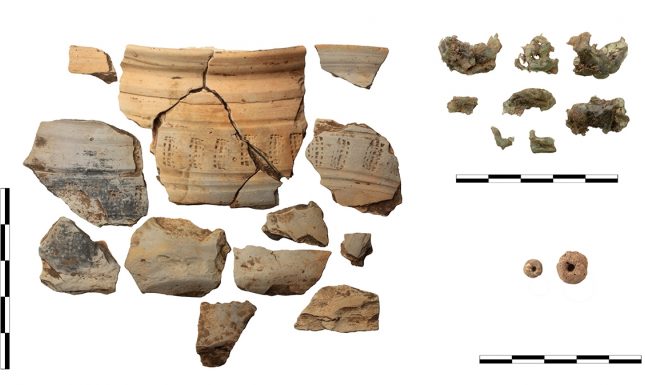

The 8th century grave of a young boy and girl underneath the Cathedral on Frankfurt shows clearly that cremation and Christianity are compatible. The grave contained two bodies, a girl whose body was inhumed and a boy whose body was cremated and deposited in a small pot. The grave was covered by a cloth with an embroidered cross. The presence of a cremated body and an inhumed body in this grave clearly points towards the acceptability of both rites within a community that was at least familiar with Christian symbology.

The cremated remains of the boy underneath the Frankfurter Dom, Germany. Depicted are the handmade pot in which the cremated remains were deposited and the bear-claw that were found amongst the cremated remains indicating that it had been burned on the pyre together with the boy. Source: dw.com

Pyres, pits and urns

Since the 19th century, the archaeological record has yielded many more early medieval cremations. Some of these burials, like the one illustrated above, indicate that an association of cremations with heathenism may not be as straightforward as has always been assumed.

First of all, there are far more early medieval cremations than previously thought, as I’ve shown in this article. Cremations also occurred until much later than previously thought and even 7th and 8th century cremations are not uncommon. Usually these cremations can be found on the cemeteries that are considered typical for this period, where inhumation graves are found in long rows. Cremations hardly occur on cemeteries without inhumations. This new data made me reconsider the dichotomy between cremations and inhumations. It suggests that there is a relation of cremations with the inhumations where they are present on the same cemeteries, instead of an opposition. Recent discoveries confirm this, as the objects deposited with cremations and inhumations show clear similarities. This only adds to their comparability.

Secondly, the introduction of Christianity is hard to date and so it is difficult to prove that cremations disappear as a result of Christianisation. As all changes in worldviews tend to be gradual, it is hard to observe from the material record how ‘Christian’ people whose remains we encounter were. To interpret cremations as a sign of heathenism is an a-priori assumption originating from modern worldviews rather than an understanding of early medieval ones. It serves only to affirm existing ideas of the past rather than to challenge the validity of normative assumptions. Moreover, it homogenises the process of Christianisation, that would have been greatly diversified and occurring at different stages and times throughout northwestern Europe.

The body of thought around cremations and their disappearance from the archaeological record is a fascinating indication on how we think change occurs in society. A uniform and abrupt change is often preferred over a more complex consideration which takes the past as a greatly diversified place with a myriad of processes and continuously changing worldviews. What early medieval cremations make clear is that such neat stories don’t exist. We’ll continuously update and localise the story we tell about the early middle ages with the new discoveries that will add to existing overviews and our interpretation of them. I am considering the relation of burial practices to social change further in my PhD project.

Literature

Masanz, R. 2010. “Brandbestattungen auf merowingerzeitlichen Gräberfeldern Süddeutschlands.” Berichte der Bayerischen Bodendenkmalpflege 51: 321–406.

Lippok, F.E. 2020. The pyre and the grave: early medieval cremation burials in the Netherlands, the German Rhineland and Belgium, World Archaeology, 52:1, 147-162, DOI: 10.1080/00438243.2020.1769297.

Cerezo-Román, J., A. Wessman and H. Williams (eds), 2017. "Cremation and the archaeology of death, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

© Femke Lippok and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Femke Lippok and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.