I Adorn You! A Deeper Dive Into Early Medieval Hair Care And Styling

Haircare and styling are both connected to a social context. By studying archaeological objects that play a role in the process of grooming, more insight can be gained into the preparational phase of a hairstyle. This gives us a broader perspective on personal care in the early Middle Ages.

The way we style our hair, as many of us have undoubtedly experienced, depends on the context. For example, there's a good chance that your hairstyle is nowadays different than it was in your childhood. And on special occasions, like a wedding or a job interview, you'll probably put more effort into your hairstyle and perhaps even go to someone who styles your hair especially for that day. Hairstyle is thus embedded in a social context and is a way to express things like age, personality, gender, ethnicity, beauty, but also competency. However, despite all the haircare products and efforts, hair has a mind of its own and the final result may not always be what you had in mind (hence the well-known bad hair day). Perhaps not surprisingly, it's not so much the final result that matters, but the act of caring and styling itself that is of importance. It is this preparational phase that the study of archaeological objects can give insight in (Ashby 2014a, 69-70, 93-95; Ashby 2014b, 155-158). Although not all hair routines and products left traces, combs and pins made of bone and antler have been found frequently at the early medieval riverine sites Oegstgeest (Merovingian) and Dorestad (Carolingian). In this blog we discuss some of these objects and what insight they offer us about the people who used them.

The comb as an heirloom

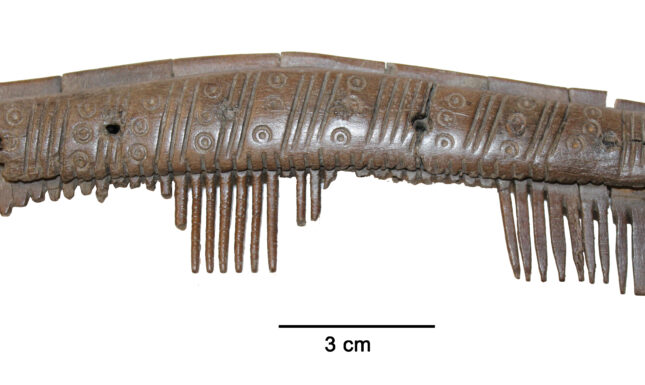

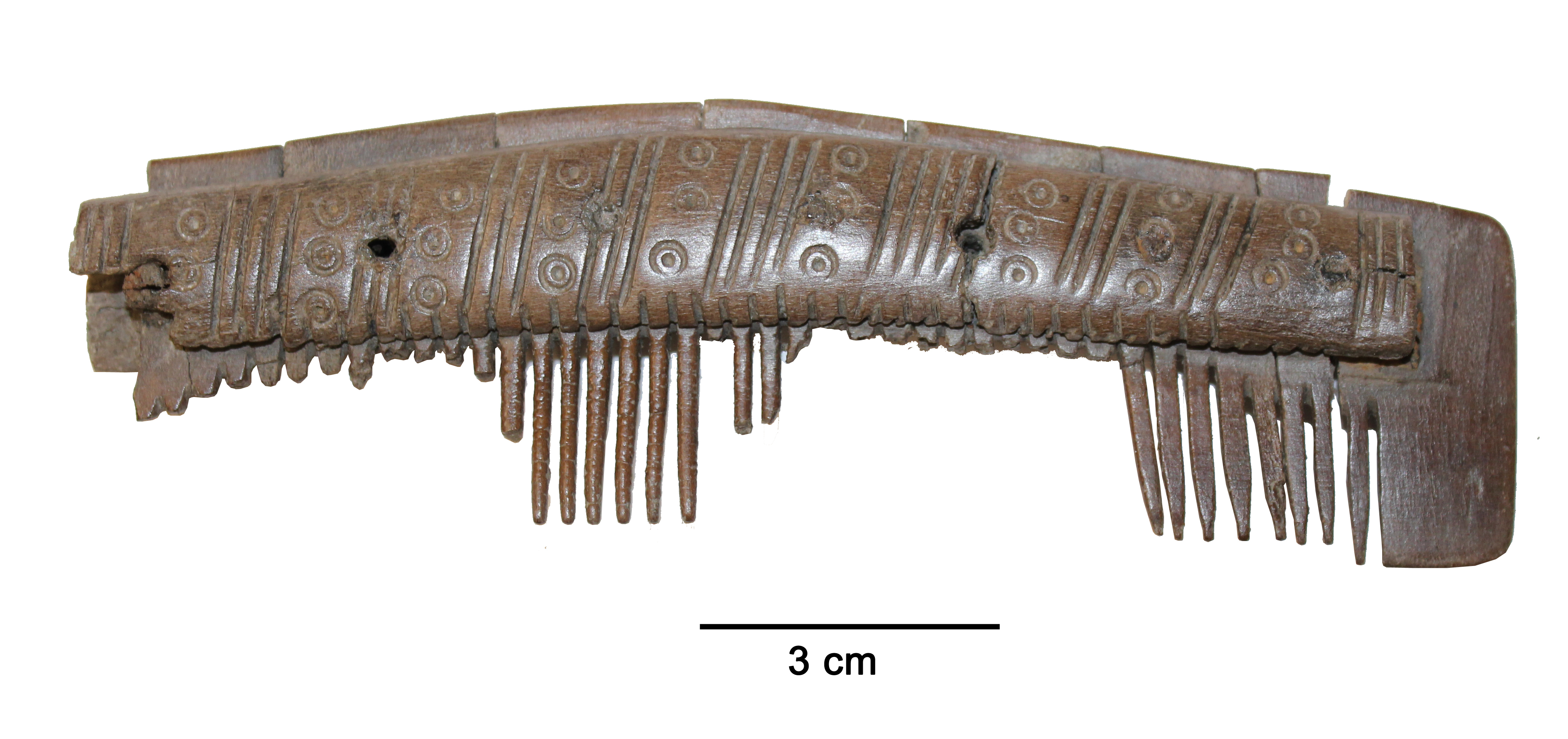

The composite comb is a type of comb that was common in the Middle Ages (Rijkelijkhuizen 2024a, 67-79). At some medieval sites it is even the largest artefact category of hard animal remains (Kromotaroeno 2015, 90). Antler was used to make these combs, although later, probably due to a shortage of raw materials, bone was mainly used. Antler was selected due to its physical properties that makes it suitable for combing. Antlers from rare species, such as the elk, were also occasionally used (Kromotaroeno 2015, 63, 81). These elaborate combs consist of multiple tooth plates, end plates and connecting plates that are connected together by means of metal rivets (see fig. 1). These combs were produced in a wide variety of types, both single-sided (row of teeth on one side of the comb) and double-sided (row of teeth on both sides of the comb) and with connecting plates in different shapes and sizes. Often the connecting plates are decorated with different types of patterns, such as ring-and-dot motifs, incised borderlines and double crossed lines (see fig. 1) (Rijkelijkhuizen 2024a, 61-65). The choices made regarding the arrangement of the teeth, the decorative patterns, the shape and the number of plates were specific to certain periods and regions (see a.o. Rijkelijkhuizen 2024a, 61; Rijkelijkhuizen 2024b, 2). By studying these combs, information can be obtained about contact and the exchange of ideas and goods. The presence of various types of composite combs in the Dutch coastal region and the Frisian terps contributes to the idea that contact was quite common in the Early Middle Ages. These sites were probably part of a larger socio-cultural exchange network (Rijkelijkhuizen 2024b, 27). The extent of which is not completely clear and further research is needed.

The organisation of the production of these combs is also shrouded in mystery. It's fairly clear, though, how these combs were produced. It was a laborious process that required specialised tools and skills (see a.o. Kromotaroeno 2015, 45). Due to the scarcity of recognisable long-term production sites, there are no clear answers to the questions of who produced the combs and where. Subsequently, it has been hypothesised that the distribution of composite combs over a larger area or region was caused by the presence of itinerant craftsmen, merchants or gift exchange (see for instance Ashby 2014a; Rijkelijkhuizen 2011, 204). Research into the collections of Dutch museums and archaeological depots suggests that the composite combs of the Dutch terps and coastal region from the 6th century onwards may have been the result of both local and centralised production (Rijkelijkhuizen 2024b, 23).

Why was so much effort put into these combs? Although research has been done on the use of these combs, the use wear traces are not yet fully understood (Kromotaroeno in prep.; Pil 2016). The teeth are covered with traces to an extent that macroscopically visible horizontal grooves have developed and sometimes even drop shaped tips (see fig. 2). Although experimental research has been conducted to better understand these traces, comparable traces have not yet been observed. This may be because these combs were used for much longer periods in the past than is normally the case in experiments. In addition, combs are complex objects with multiple teeth. Differences in the distribution of use wear traces on the teeth may occur depending on the type of use. Conducting further experiments may provide clarity in this regard. Based on the laborious character of the combs and the high degree of wear, it is thought that these combs had special significance to the user and were passed down through generations (Rijkelijkhuizen 2011, 200). Some combs ended up in the grave (Ashby 2014, 123-132).

Let's sew the hair together

Hair can also be styled with the aid of needles and pins. One of the bone needles from Oegstgeest is associated with hairstyling (inv.no. 406) (see fig. 3). Although the head and tip have broken off, the surface is preserved well enough to allow the traces to be interpreted (Kromotaroeno 2015, 71). The remains of an eye hole suggest that a thread was pulled through the hair. The needle may have been used to attach a hairnet to the hair (see Struckmeyer 2011, 63). However, no traces of this were found on the needle of Oegstgeest. Another possibility is that the needle was used to sew the hair together with threads to create the desired style (Stephens 2008, 112, 115-116).

A fragment of a hairpin made of bone or antler was found in the Dorestad collection (National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden, inv.no. WD 364). Hairpins have one pointed end. The other end is often decorated. Although only the pointed end of the pin has been preserved, it still provides insight into the decisions made during the object's production and use (Kromotaroeno 2025). The highly worked needle clearly stands out from most needles studied from Dorestad in terms of production (Kromotaroeno in prep.). Hairpins can only hold hair in place if the hair is long enough and tightly twisted or coiled. In order to stay in place, the broad, decorated end should stick out above the coiled or twisted hair (Stephens 2008, 112, 115-116).

Haircare can reveal more than meets the eye

The preparational phase of a hairstyle is a phase that is easily overlooked. Ironically, this is the time of day we spend most time on our hair, yet it is the end result that is most often captured in photographs and therefore most remembered. Studying archaeological objects used in haircare and styling provides a broader perspective on personal care and adornment. One that contains the biography of these objects and gives them a place in the lives of the people who used them. You could argue that the preparational phase of a hairstyle starts with the production of these objects. The choices made during production, from the selection of raw materials to decoration, are all made with a specific purpose in mind. A purpose that fitted within the existing customs of the time. The production and (re)use of the composite combs, hairpin and needle discussed in this blog all contribute to the idea that haircare was of significance in the Early Middle Ages, as something that was – in a sense – firmly embedded into early medieval society.

Further reading

Ashby, S.P., 2014a: A Viking Way of Life: Combs and Communities in Britain and Scandinavia, c. AD 800-1000, Stroud.

Ashby, S., 2014b: Technologies of appearance: Hair behaviour in early medieval Europe, The Archaeological Journal 171, 151-184.

Kromotaroeno, C.L.S., 2015: Osseous objects of Oegstgeest. A functional analysis of the bone and antler objects of the Early Medieval settlement of Oegstgeest (Nieuw-Rhijngeest Zuid), Leiden (unpublished MSc thesis Leiden University).

Kromotaroeno, C.L.S., 2025: In short: Needles and what they tell us about Dorestad, in A. Willemsen/ H. Kik (eds.), 2025: Dorestad and everything after. Ports, townscapes & travellers in Europe, 800-1100, Leiden (Papers on Archaeology of the Leiden Museum of Antiquities (PALMA), 35), p. 109-114.

Pil, N., 2016: Vroegmiddeleeuwse kammen: Hoe werden ze geproduceerd en gebruikt op de sites van Quentovic en Hamage?, Brussel (unpublished Ma thesis Vrije Universiteit Brussel).

Rijkelijkhuizen, M.J., 2011: Dutch Medieval Bone and Antler Combs, in J. Baron/B. Kufel-Diakowska (eds), 2011: Written in Bones: Studies on Technological and Social Contexts of Past Faunal Skeletal Remains, Wroclaw, 197-206.

Rijkelijkhuizen, M.J., 2024a: Osseous and keratinous artefacts in the Roman and Early Medieval period (12 BC-1050 AD), in M.J. Rijkelijkhuizen/J.T. Zeiler/J. van Dijk (eds.), 2024: Osseous and keratinous objects from the Netherlands, Amersfoort (Nederlandse Archeologische Rapporten, 84), 49-99.

Rijkelijkhuizen, M.J, 2024b: Op zoek naar de Friese kam. Een kammentypologie voor het Nederlandse grondgebied, Archeologie in Nederland 8/3, 20-27.

Stephens, J., 2008: Ancient Roman hairdressing: on (hair)pins and needles, Journal of Roman Archaeology Vol. 21, 110-132.

Struckmeyer, K., 2011: Die Knochen- und Geweihgeräte der Feddersen Wierde. Gebrauchsspurenanalysen an Geräten von der Römischen Kaiserzeit bis zum Mittelalter und ethnoarchäologische Vergleiche, Köthen.

© Cynthia Kromotaroeno and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Cynthia Kromotaroeno and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.