Hogs and Heraldry: Medieval Pigs on Coats of Arms

From signs of bravery to puns on family names, swine are a frequent sight on medieval coats of arms.

A boar in a cape: Jan III van Brabant and his boar emblem

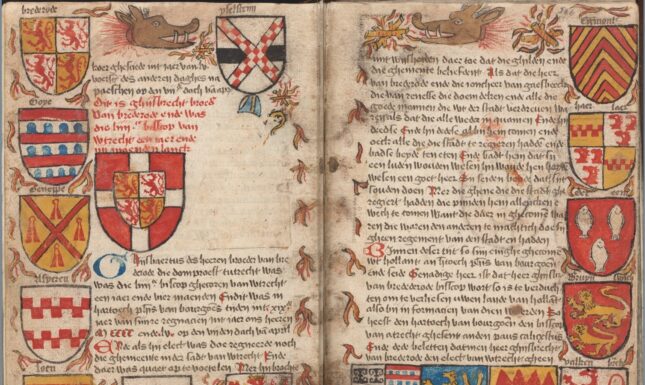

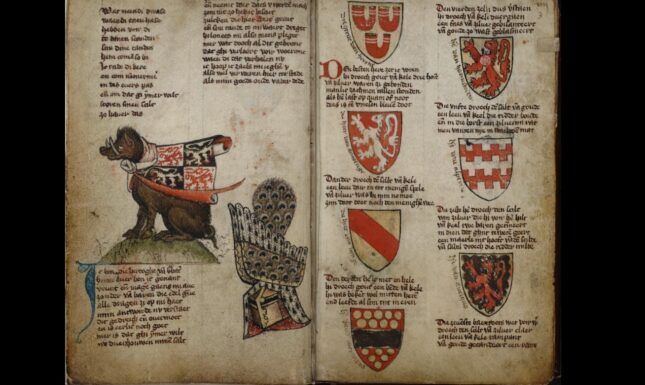

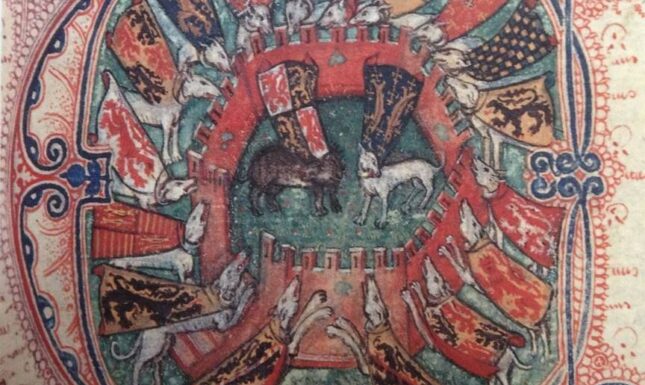

The famous Gelre Armorial (c. 1395-1414) contains depictions of over 1800 medieval coats of arms. One of its pages has a curious sight: a sitting boar, wearing a cape, embroidered with a quartering of two coats of arms (Brabant/Limburg):

This cape-wearing boar is accompanied by a short poem in Middle Dutch 'Van den Ever' [About the Boar] which identifies the animal as Jan III, Duke of Brabant (c. 1300-1355):

"Ic ben die hertoghe van Brabant. / Bi den Ever ben ic genant." [I am the Duke of Brabant, I am nick-named the Boar]

The poem reimagines a 1334 war between Jan van Brabant and no fewer than seventeen nobles as a hunt for a boar by seventeen hunting dogs. The escutcheons (shields with coats of arms) of each of these nobles are also depicted in the Gelre Armorial, accompanied with verses that threaten the boar. The text underneath the escutcheon of the Duke of Gelre, for instance, reads:

Heer ever, ic moet

In u bloet

Mijn tende netten;

Want u en kan

En gheen man

Nu ontsetten.

[Lord Boar, I must now set my teeth in your blood, because no man can free you now]

Judging by the poem, Jan 'the Boar' III van Brabant was not impressed by the dogs' threats: "Dit gedreich ende overmoet / En is eerlic noch goet" [This threatening and over-bearing pride is neither honest nor good].

Indeed, the coalition of seventeen nobles was unable to fully defeat Jan van Brabant, who managed to come out of the 1334 conflict without losing any land. Clearly, the boar (known for its ferocity and fearlessness) was an apt heraldic animal for this brave duke.

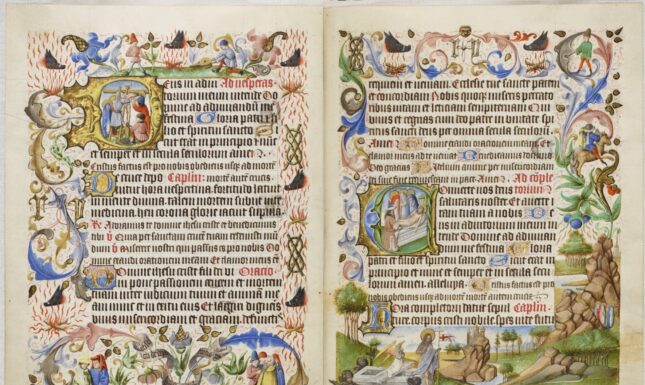

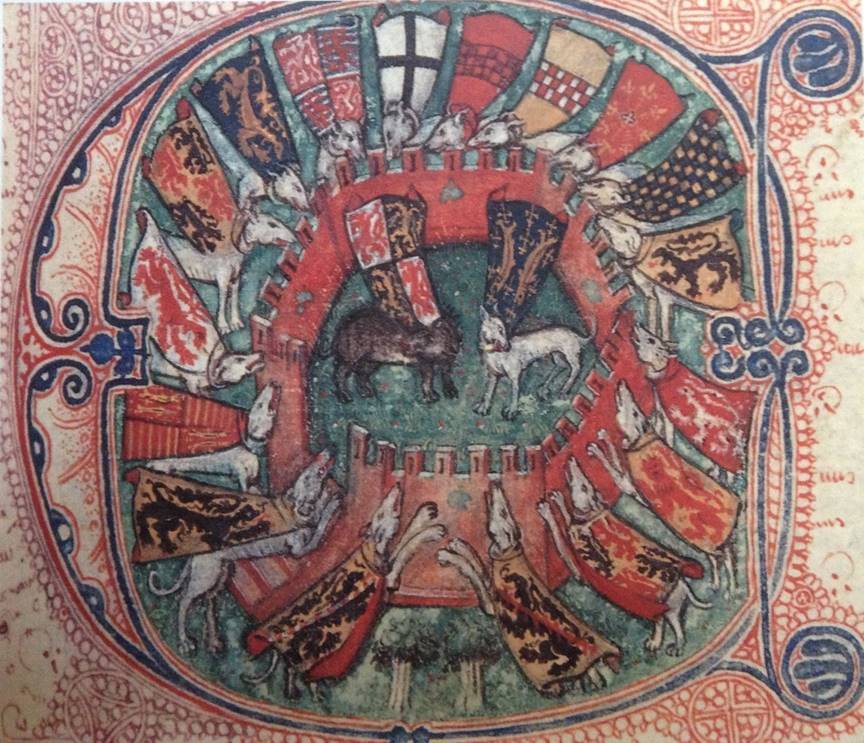

The poem appears to have made quite an impression and was clearly remembered almost a century after the 1334 conflict, when a depiction of the poem was added in an illimunated initial of a charter from 1438 (Appelmans 2017). Here we see a boar wearing the same quartered cape, surrounded by seventeen hunting dogs each wearing the coats of arms of the opposing nobles. Standing by the boar's side is a white dog wearing a cape with the arms of the Duke of Bar, Jan's only ally.

That Duke of Bar also makes an appearance in the poem 'Van den Ever', in which he warns the seventeen dogs for the boar's fierceness:

Wat meendi, dwase?

Waendi enen hase

Hebben voir di?

...

Ic rade di, kere!

En com nemmermere

In des Evers pas.

[What do you think, fool? Do you imagine that you have a hare in front of you? I advise you: turn around! And never come in the boar's path again!'

A boar is not a hare - something any hunting dog would do well to remember!

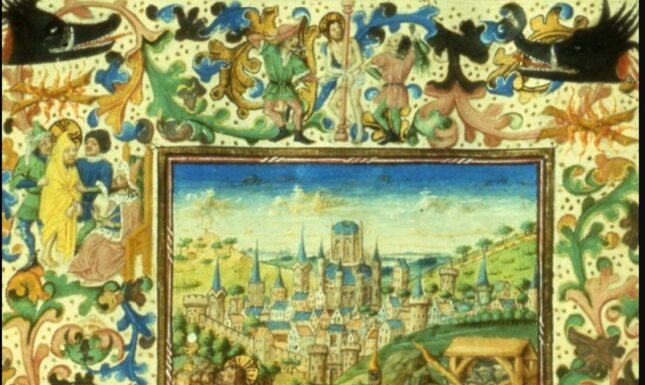

Burning the boar's head: The Brederode boar

Jan van Brabant was not alone in picking the boar as his heraldic animal. The boar's reputation for bravery and fortitude made it a popular pick for many nobles, including, famously, Richard III of York (1411-1460), whose white boar emblem also tapped into a tradition of royal prophecies surrounding boars (see The boar who would be king: Royal boar prophecies in medieval England). In the Low Countries, a notable example of a noble family adopting the boar as its heraldic animal is the Brederode family, who used the boar's head above two burning branches as their emblem since the 15th century. Examples of their burning boar's heads can be found in various places, as the following 'image carousel' will demonstrate:

Nomen est omen: Canting arms

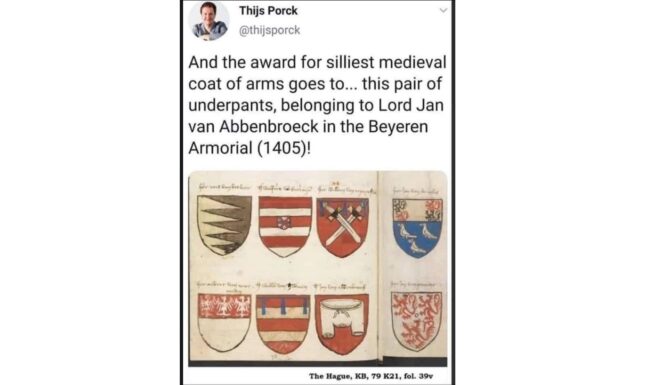

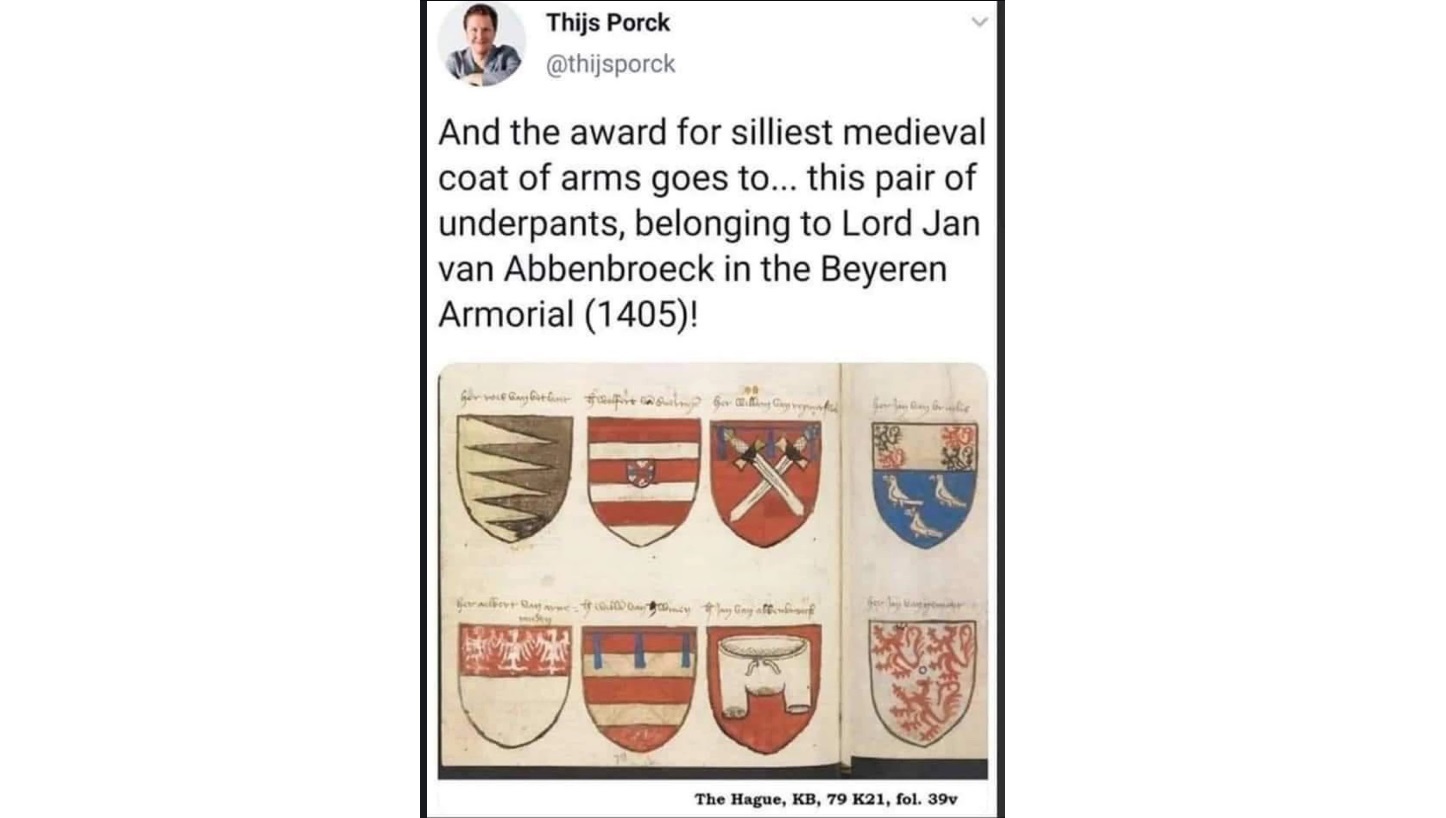

Aside from the boar's positive qualities and their associations with noble standing (the boar's hunt was a typically aristocratic pastime), there was also another reason why some noble families picked this particular animal: because pigs could visually represent their name. A coat of arms in which heraldic images represent the bearer's name are known 'canting arms'. These can be quite humorous, as the following viral tweet demonstrates:

What makes this coat of arms particularly funny is that the element 'broeck' in the name Abbenbroeck could mean 'breeches', but surely derives from Old Dutch bruoc, brōk 'marshy land'.

Pigs on canting arms are typically found in the heraldic weapons of towns that were named after pigs, including Schweinberg (swine-mountain), Eberbach ('Boar-brook') and, of course, Pigtown (see: Hogwarts in the Middle Ages: Piggy Place Names in Early Medieval England). Some noble families, too, picked pigs to represent their names, including the Sweeney's and Swinfields. This explains the presence of several little pigs around the 14th-century tomb of John Swinfield in Hereford Cathedral:

Sometimes, the pigs represent the meat products made from these animals, as is the case in the coats of arms of the Bacon family, as depicted in the 15th-century Paston Book of arms:

And from Bacon, it is only a little step to Pork, or Porck...

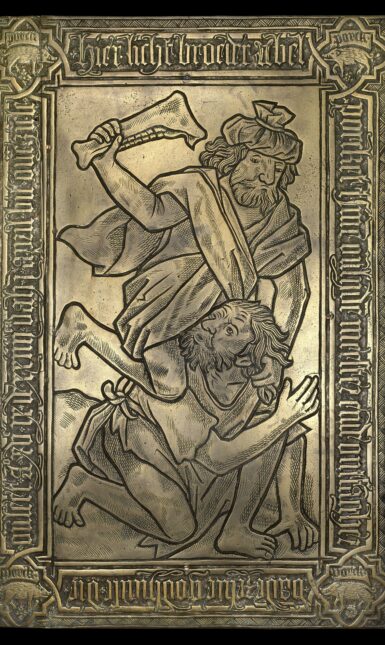

Hitting close to home: The memorial plaque of Abel Porcket (d. 1509)

As readers of the many hog blogs on the Leiden Medievalists Blog may have assumed, my interest in medieval pigs stems, in part, from my own last name, 'Porck'. Therefore, I figured it would be a fitting end to this blog post to make mention of an early 16th-century crest featuring a pig along with the inscription "PORCK":

These four piglets bearing my last name are found on a memorial plaque of one Abel Porcket, hospital master of the St. Julian's House of God in Bruges. Judging by the text on the edges of the plaque, this Abel Porcket died in the year 1509:

"Hier licht broeder abel porcket tsinen overlijden meester ende ontfanger van den zelve godshuuse die overliet a[nn]o xv(c) ix den xxiiij-en dach in april bit over ziele."

[Here lies brother Abel Porcket, at time of his death master and receiver of this very House of God who died in the year 1509, the 23rd day of April, pray for his soul]

The iconography on the plaque probably does not represent his family crest but, instead, is a play on his first and last name. His first name, Abel, is symbolized by the large depiction of Cain killing Abel with the jaw-bone of an ass. The quartet of 'Porcks' stand for his surname: Porcket.

While it is unlikely that Abel Porcket and I are related, I do wonder whether it is possible to register his coat of arms for myself - what could be more fitting for a medieval(ist) Porck?

Sources

- Appelmans, Janick. "Werd het wapendicht 'Van den ever' in 1438 te Leuven opgevoerd?", ES&DB:Tijdschrift voor Brabantse Gechiedenis 100 (2017), pp. 469-84.

- Digitized version of the Gelre Armorial: https://uurl.kbr.be/1733715 (see also the very useful schematic version in WappenWiki: https://wappenwiki.org/index.p...)

- Abel Porcket plaque in Gruuthuse Museum, Bruges: https://collectie.museabrugge....

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.