The boar who would be king: Royal boar prophecies in medieval England

Various medieval English kings sought to identify themselves with the boar, including Henry II, Edward III and Richard III of York. This blog calls attention to the role of the boar in medieval English royal prophecies.

King Arthur as the Boar of Cornwall

The frequent use of the boar in royal prophecies in medieval England can be traced back to Geoffrey of Monmouth's famous Historia Regum Britanniae (c. 1136). Book 7 of this foundational work of the Arthurian legend describes the prophecies of Merlin. These prophecies include a list of various animals who represent future rulers of Britain, including the White Dragon, the Lion of Justice and the Hedgehog (who will rebuild a town and lure many birds with the apples on its spines). Greatest among these animals is the 'boar of Cornwall':

“For a boar of Cornwall shall give his assistance, and trample their necks under his feet. The islands of the ocean shall be subject to his power, and he shall possess the forests of Gaul. The house of Romulus shall dread his courage, and his end shall be doubtful.”

This boar of Cornwall turns out to be none other than King Arthur, who comes to the aid of the Britons, conquers France and also attempts to conquer Rome. The "doubtful end" may anticipate Arthur's departure for Avalon, mortally wounded but not quite dead.

Since Arthur came to be regarded as the epitome of the ideal king, various English monarchs have tried to link themselves to the Arthurian legend. As a result, the boar also became a popular royal symbol, found in various texts that are based on the tradition of Merlin's prophecies.

Boar-pretenders: Henry II and Edward III

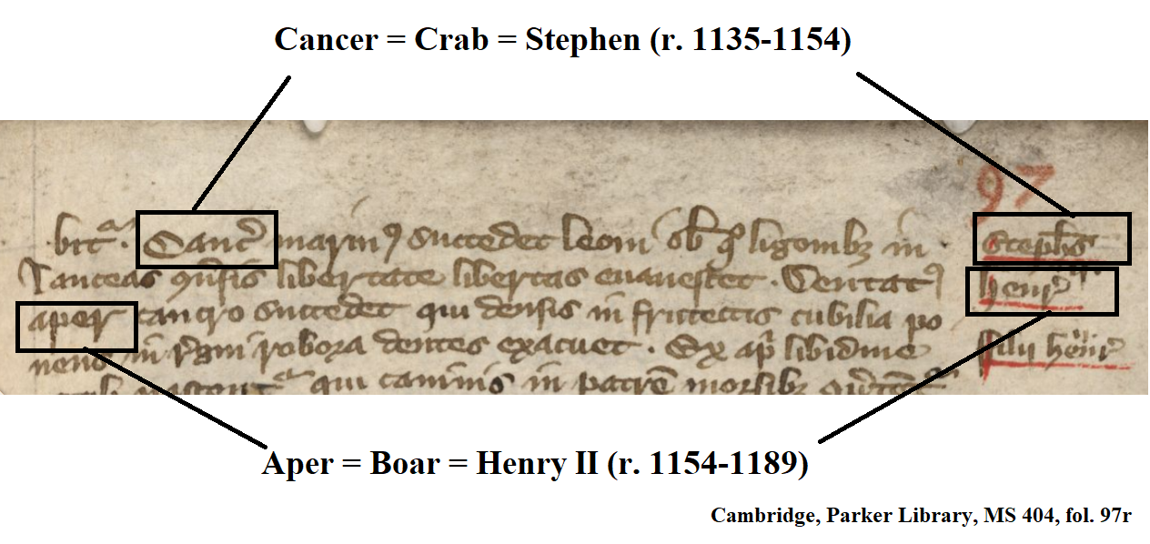

A 14th-century, Latin copy of a list of Merlin's prophecies now in Cambridge, Parker LIbrary, MS 404, spelled out the symbolic interpretation of Merlin's prohetic animal-rulers by adding the names of prior English monarchs in the margin. The "Lion of Justice", for instance, was identified as Henry I (r. 1100-1135); the Crab whose reign brings war and suffering was associated with the unfortunate Stephen (r. 1135-1154); and their succesor was the heroically tusked boar Henry II (r. 1154-1189).

The tradition of Merlin's prophecies was not only used retrospectively, to make sense of the succession of prior rulers, but it could also be applied for propaganda purposes. This appears to have been the case for Edward III (r. 1327-1377), who sought to associate himself with the "Boar of Windsor". According to a version of Merlin's prophecies that circulated with the Middle English Brut Chronicle, this boar of Windsor would succeed the malfunctiong Goat:

“Aftre þis goote, shal come out of Wyndesore a Boor, þat shal haue an heuede of witte, a lyons hert, a pitouse lokyng; his vesage shal be reste to sike men; his breþ shal bene stanchyn of þerst to ham þat bene aþrest þerof shal; his worde shal bene gospelle; his beryng shal bene meke as a Lambe... and he shal whet his teiþ vppon þe gates of Parys.” (source)

This image of a heroic, holy boar that would 'whet his teeth on the gates of Paris' was appealed to by the poet Laurence Minot (1300-1352), when he celebrated the victories of Edward III against the French in Normandy during the 1340s:

“Merlin said thus with his mowth:

Out of the north into the sowth

suld cum a bare over the se

that suld make many man to fle.

And in the se, he said ful right,

suld he schew ful mekill might,

and in Franse he suld bigin

To mak tham wrath that er tharein.” (source)

Thus, the boar from Merlin's prophecies became a powerful symbol that could be used by kings to raise their status (see, e.g. Coote).

The last royal boar: Richard III

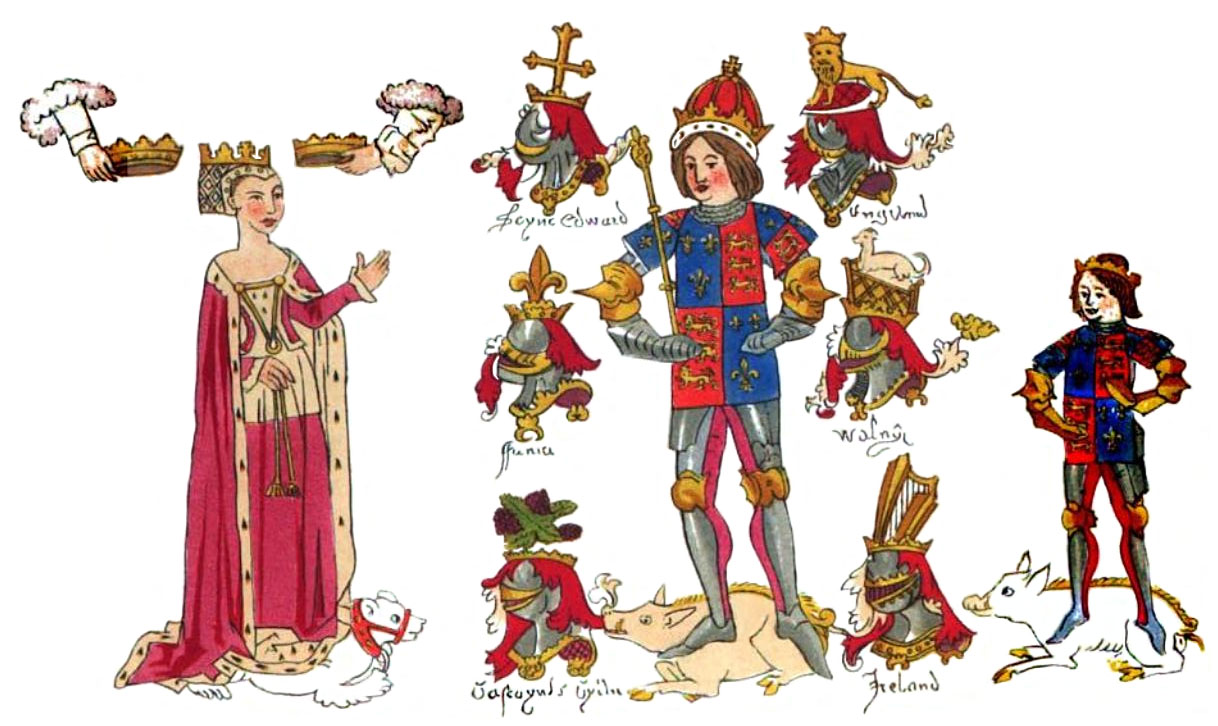

Richard III and his family (and his boars) on the Rous Roll. London, British Library, Add MS 48976 (WikiCommons)

The English royal most famous for his use of the boar as a sigil was King Richard III (r. 1483-1485), whose followers wore livery badges with the image of a white boar. Belonging to the House of York, the use of the boar has been associated with the English etymology of York (eofor-wic 'boar-town'), but it is possible that Richard, too, was inspired by the (predominantly positive) portrayals of the boar in the tradition of Merlin's prophecies. Be that as it may, Richard's reign would not last long, nor was it as positive as the boar-ish reigns once prophesized by Merlin. In 1485, Richard III died in the Battle of Bosworth, which was won by Henry Tudor. The Welsh poet Guto'r Glyn, in a poem priasing one of Henry's Welsh knights, referred ironically to Richard as a boar:

"King Henry won the day

through the strength of our master

He killed Englishmen, capable hand

He killed the boar, he chopped off his head" (source)

Perhaps it is Richard III's eventual loss and his strong association with the boar that has led to the fact that no other English royal would ever appeal to the royal boar prophecy again. However, it is possible that the printed edition of Thomas Mallory's Le Morte Darthur also played a role.

How a bear became a boar: Mouvance in William Caxton's Le Morte Darthur (1485)

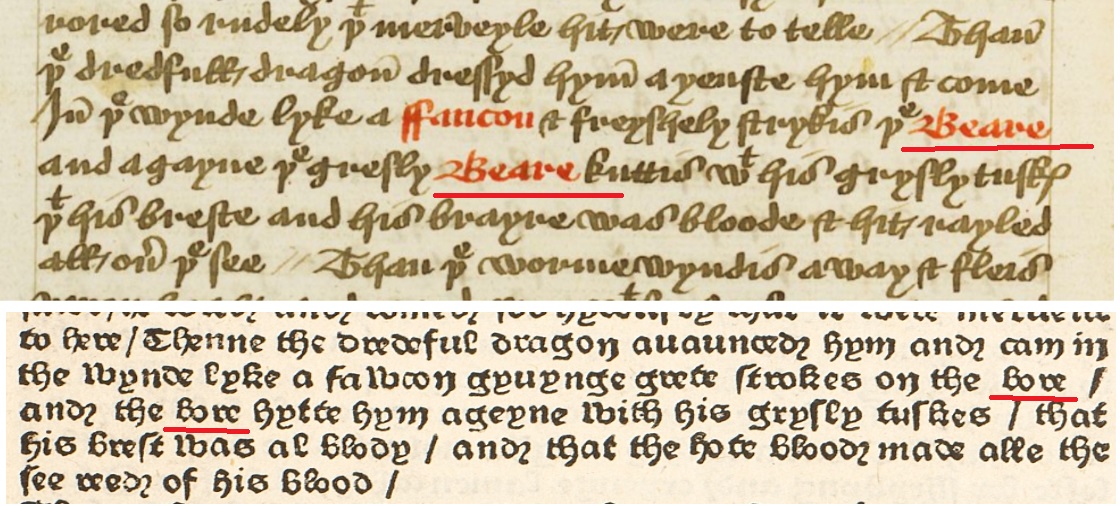

The most widely read version of the Arthurian legend is Le Morte Darthur by Sir Thomas Mallory, composed some time before 1470. The text of this work survives in a printed edition by William Caxton, dated to 1485, and the so-called 'Winchester Manuscript' (London, British Library, Add. 59678). This Winchester Manuscript is dated to a decade after Thomas Mallory's death in 1471 and was probably used by Caxton in his print shop, along with another manuscript now lost. Comparing the Winchester Manuscript to Caxton's later printed edition allows a glimpse at how Caxton made subtle alterations in Mallory's text. Crucially, for the purpose of this blog, Caxton changed the text of a prophetic dream that King Arthur has while he is on his way to conquer Rome in book V, chapter 4. According to the Winchester manuscript, Arthur dreams of how a dragon defeats a "gresly Beare"; after Arthur wakes up a philosopher explains that Arthur need not worry: he is the dragon that will defeat the bear, who symbolises a cruel and powerful tyrant that torments its people.

London, British Library, Add MS 59678, fol. 75v and the corresponding passage in Caxton's Le Morte Darthur (1485)

In Caxton's version, printed in 1485, the bear has been changed into a boar: "the bore"! This appears to be a conscious change, inspired by the political situation of the day, as P. J. C. Field has noted:

“In C, the bear is (six times) turned into a boar. The change must have been deliberate, and it created a bold political allusion: the boar was the badge of King Richard III and the dragon that of Henry Tudor. The allusion would only have made sense in or just before 1485, and it is difficult to see who could have been responsible for it but Caxton himself …” (cited in Crofts)

By exchanging the bear for the boar, Caxton has altered Mallory's prophetic dream to be a comment on the political situation of 1485. Notably, the dream, as altered by Caxton, came true! Caxton had published his Le Morte Darthur on the last day of July 1485 and, less than a month later, Henry Tudor, flying a dragon banner, defeated Richard III, flying a boar banner, at the Battle of Bosworth on 22 August 1485.

Following Richard III, no other English monarch seems to have appealed to a royal boar prophecy. Perhaps this was, in part, due to Caxton's introduction of an alternative, negative royal boar prophecy that featured prominently in one of the most popular works of the Arthurian Legend.

Bibliography:

- Lesley Coote, Prophecy and Public Affairs in Later Medieval England (Woodbridge, 2000)

- P. J. C. Field, “Caxton’s Roman War,” Arthuriana 5 (1995): 31-73.

- Thomas Crofts, Malory's contemporary audience the social reading of romance in late medieval England (Woodbridge, 2006)

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.