Getting Pregnant and Treating Infertility in Renaissance Italy

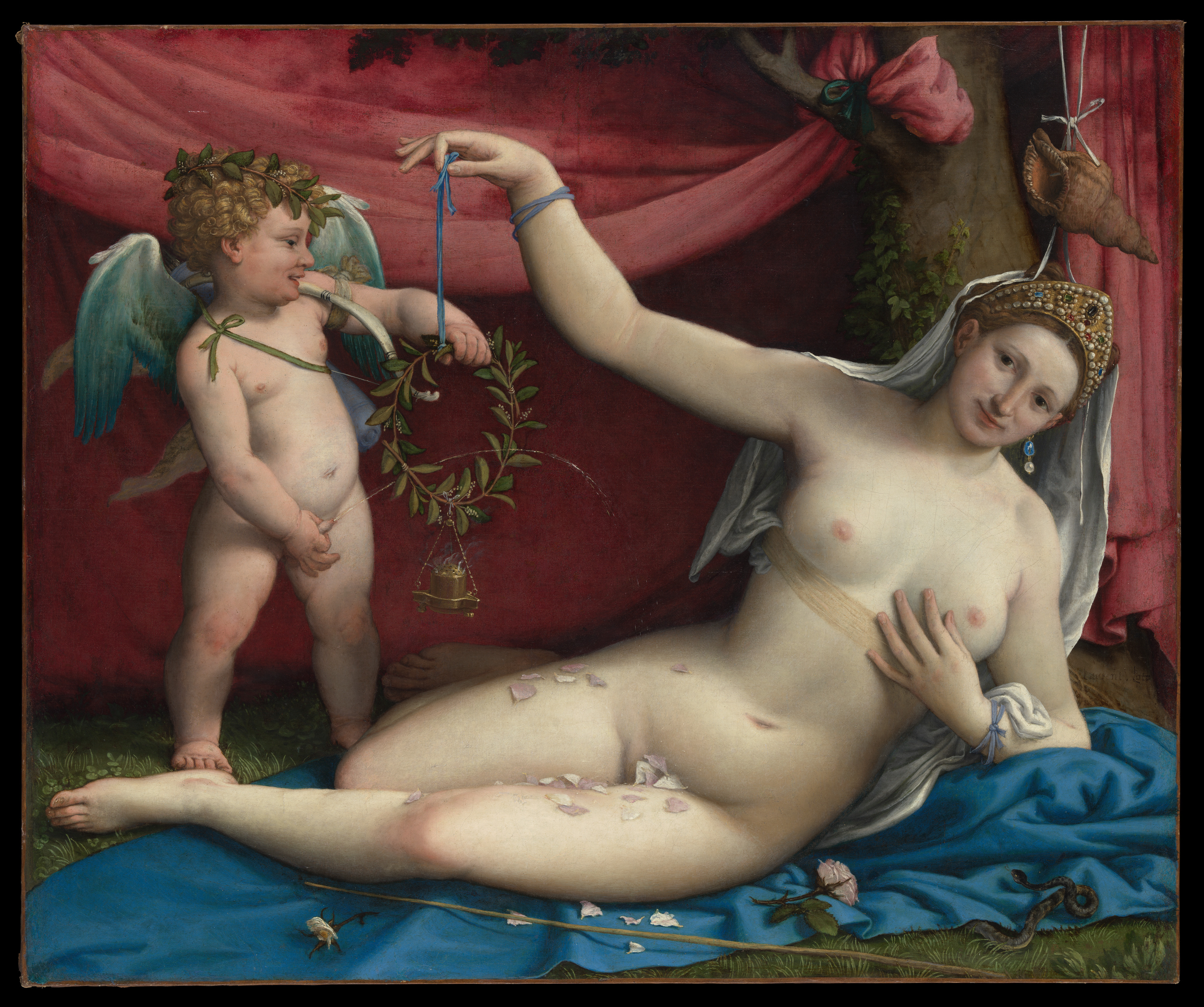

Deciding that you are ready to have children can be a joyous milestone. However, if a pregnancy does not occur, the experience can become a significant source of stress. How did people in Renaissance Italy deal with infertility?

When researching sexuality, one often encounters similarities between ourselves and the people of the past. Certain emotions and preoccupations appear to be timeless and universal – they are part of the human experience. For thousands of years, people have dealt with the same issues, worrying about the same things that are beyond their control: things like being cheated on, not fitting in, or not being attractive enough.

One anxiety we share with Renaissance Italians is the fear of infertility, though significant differences remain. In Renaissance Italy, most people’s desire for offspring would be partly if not primarily based on religious and socio-economic reasons. Christian theology taught that the main goal of marriage was generating children who would be raised within the faith and who would live to serve God. For the elite, producing (male) heirs was vital to continue the family’s dynasty and protect its patrimony, and within the lower classes, children could contribute to the household.

Another thing that sets us apart is the ability to control the process of procreation. While modern doctors are still unable to solve all cases of infertility, their abilities still dwarf those of their earlier counterparts. This blog post will focus on the writings of two university professors from Renaissance Italy, Michele Savonarola and Pietro Bairo, on the topic of getting pregnant and treating infertility.

Improving one’s chances

Michele Savonarola’s treatise on conception and childbirth, Ad mulieres ferrarienses, includes some of the most elaborate and explicit advice on how to get pregnant. He offers his readers a step-by-step-guideline including advice on timing and foreplay.

A proper timing was considered vital. Couples needed to carefully plan intercourse so that the circumstances were as favorable as possible, starting with the right season. They should have sex during the winter and the spring, because when it is cold, the bodies are warmer, stronger and full of spirit. The female menstrual cycle was taken into account as well (even though knowledge of the workings of this cycle was still lacking). It was considered best to have sex about eight days after the woman had stopped menstruating, because at that time the uterus “receives the semen with much more appetite and delight”. It was also very important not to have sex on a full stomach just after dinner, but about six or seven hours after the meal. Finally, couples needed to optimize the frequency of their relations – the quality of the semen was best when one had sex about once every five days.

After pinpointing the right moment to have sex, Savonarola moves on to the mechanics of the act. He instructs his male readers on touching a woman to increase her pleasure. As a follower of the Galenic two-seed-theory, Savonarola believed that both men and women needed to have an orgasm and ejaculate semen simultaneously in order to generate a child. When the man ejaculates, Savonarola advices him to to do so in one breath, not in multiple strokes, and to resist the temptation to pull out and in, but to stay fixed so that no air can enter and thus corrupt the semen. After the climax, the woman has to lift her legs up into the air and stay this way for six hours (!) so that the sperm can descend into the uterus and no air can affect the sperm. She should try to sleep in this position, as this would draw the heat inwards and make the sperm warmer and stronger.

Pointing fingers

Couples looking to get pregnant could use tips like those of Savonarola to improve their chances. But what if, after all this, a pregnancy failed to materialize? Renaissance doctors offered advice in those cases as well. The first step was to determine the cause of the problem. They described a wide array of strange experiments that were supposed to discover whether “the fault”, as they put it, lay with the man or the woman.

Some of these experiments made use of urine samples. Two examples can be found in Pietro Bairo’s Secreti Medicinali:

Take two vases of earth and give them a sign, so that you know the one from the other, put barley in both and have the woman urinate in the one and the man in the other. Put the vases in a cold place for twelve days, and the fault lies with the one whose barley does not germinate.

Another: put semolina in two signed vases like above. The man urinates in one, the woman in the other, and leave it for nine days. The fault lies with one in whose vase are worms and whose semolina reeks. And if the same is found in both vases, they are both sterile, and if it is found in neither vase, you can make them apt to generate by way of medicine.

Other experiments, described by Savonarola, employed the senses of smell and taste in order to uncover potential internal blockages. One could for instance apply saffron underneath a patient’s eyes, and if they were unable to taste the flavor inside their mouths they were infertile, because this was a sign that the passage between the brain and the testicles was blocked. Similarly, one could put a cloth with something fragrant, or even a clove of garlic into a woman’s vagina, and if she could not taste it, she was infertile.

Oils, pills, baths and smoke

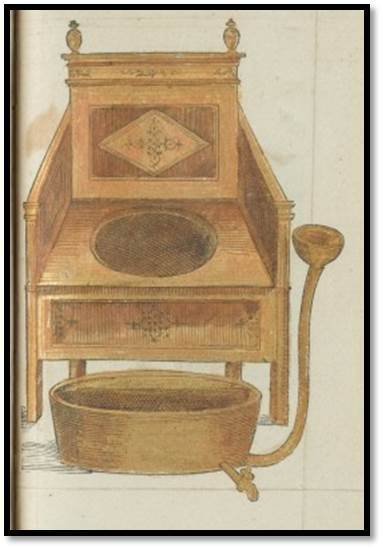

While internal blockages were perceived as a potential cause for infertility, most cures were focused on something else: curing excessive humidity and lack of warmth. According to Pietro Bairo, when women are unable to conceive, this is usually the result of an “overpowering humidity of the uterus”. This can be cured with a wide range of methods, including herbal oils anointing the belly, oral medicine made from a plant known as fox’s testicles, and warm herbal baths. Other medicine was applied more locally through the use of suppositories or fumigations. Women were advised to wear a sachet filled with ingredients like cypress and amber in their vagina for three mornings in a row. Or they could burn incense, myrrh, laudanum, and cypress, place a perforated chair above, and sit on this chair with their genitals exposed so that the smoke could rise up into her vagina.

Michele Savonarola’s treatise mentions the use of fumigations and suppositories as well. These supposedly expelled superfluidities, comforted the uterus, and increased its temperature. Increasing the temperature was considered especially important, as heat was believed to improve the chances of conception, as well as the chances of generating male instead of female offspring – something considered very important, as I discussed in a previous blog. Warm aromatics like musk should be placed around the genitals during sex and women should also be careful not sit on the ground, but to always sit on a chair and a cushion made with feathers.

~

One striking feature of the discussion on infertility is the focus on the female rather than the male body. Pietro Bairo’s chapter on how to make a woman pregnant consists of 4,5 pages with remedies, but only two of these remedies are aimed at men: tempering their temperature and checking if their semen is prolific. The rest is aimed at women either explicitly (by the use of lei or la donna) or implicitly (by the addition of “after the menstruation” or “when you use yourself with a man”. While Michele Savonarola gives advice to men as well, most of his fertility investigations and treatments were likewise centered on the female partner. Interestingly, while Renaissance doctors generally considered the female body inferior to that of the male, both in its physiology and in its contribution to procreation, they nonetheless allocated the greater share of responsibility to women.

Primary sources

Pietro Bairo, Secreti Medicinali (Venice: Ventura de Salvador, 1585).

Michele Savonarola, Ad mulieres ferrarienses de regimine pregnantium et noviter natorumusque ad septennium (ed. by Luigi Belloni: Il trattato ginecologico-pediatrico in volgare, Milan 1952).

© Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2026. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.