Boy or Girl? Gender Reveal in Renaissance Italy

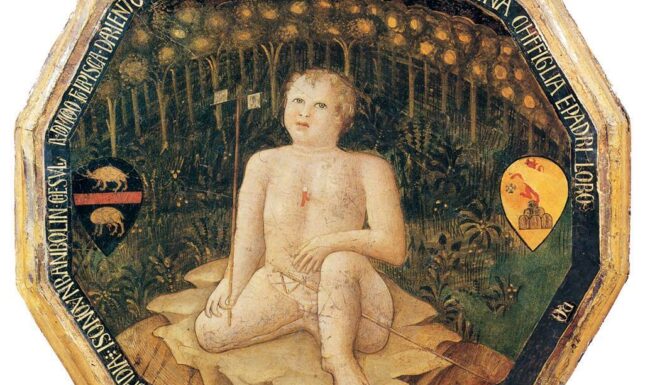

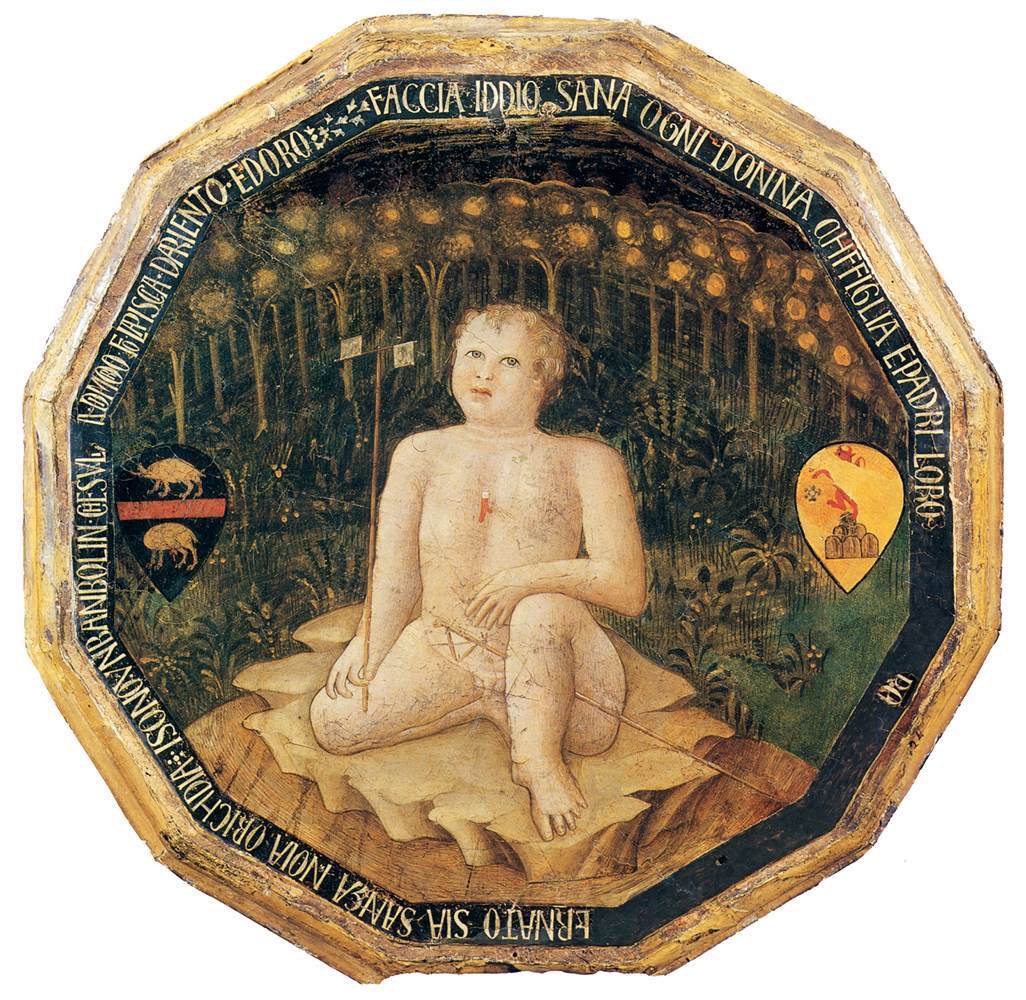

Gender reveal parties have become increasingly popular, while at the same time being criticized for reinforcing stereotypes. Renaissance Italy had its own party tricks to reveal whether an unborn child was a boy or a girl. A clear preference for boys, however, made these tricks far from festive.

Gender reveal: the misogynous approach

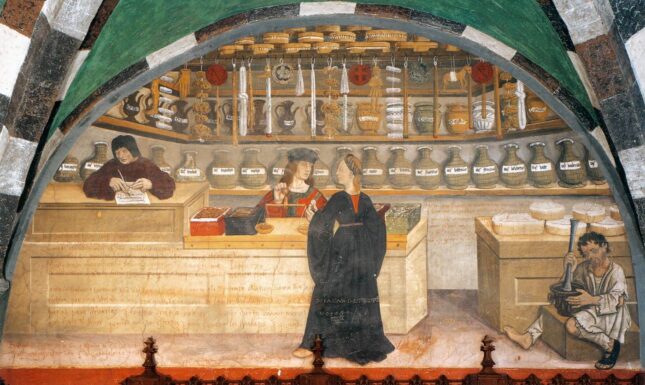

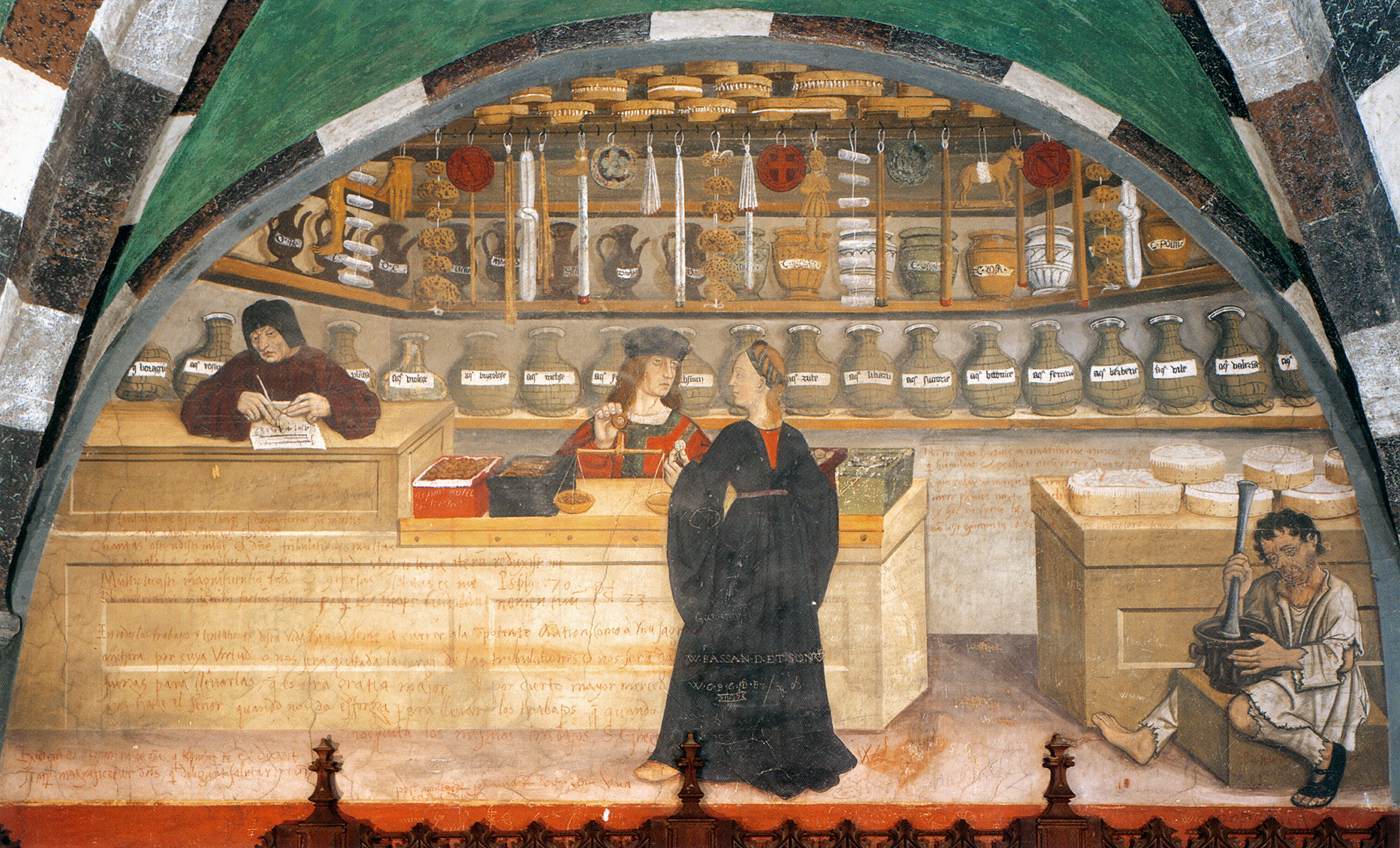

In our own day and age, medical technology allows us to discern the sex of an unborn baby about sixteen weeks into the pregnancy. Needless to say, there was no such technology in the fifteenth or sixteenth century, but curious (or anxious) expectant parents did have access to a variety of medical experiments. University professors like Pietro Bairo and Michele Savonarola provided their readers with numerous ways to discover whether the conceived fetus was male or female. Many of these were based on the ancient idea that the male fetus is located on the right side of the uterus, and the female fetus on the left side. Both medics for instance claim that a woman carrying a male child puts her right foot first in walking and has a pulse that is quicker on the right side, while Savonarola also adds that the woman’s right breast starts to grow long before the left one does.

To a modern reader, this kind of advice still seems funny and harmless, but many other so-called signs reveal clear misogynous perceptions. If the body of the pregnant woman is round, solid, and strong, it is a boy. If her body is long, weary, and spotted, it is a girl. If the woman has a good complexion, a bright face, is light, agile, and has a good appetite, she is pregnant with a boy, whereas a woman pregnant with a female child has a bad complexion, ulcers, pustules and spotted feet. These physical signs imply that carrying a female child brings more harm to the female body than carrying a boy. The medical “logic” behind this idea was that male children are supposedly made from warmer semen and warmer and purer blood, and that a uterus carrying a female child also makes superfluities that are expelled to the exterior (resulting in a spotted, ulcerated skin). According to the following experiment provided by Savonarola, women pregnant with a male child also have a much better digestion:

Make a suppository out of a radice di astrologia longa, drench it in honey, wrap it in greasy cloth and put it inside the natura [i.e. the vagina] in the morning and keep it there till midday. If the woman tastes a sweet flavor in her mouth, it is a male child, if it is bitter, it is a female child. This is because sweetness is a sign of good digestion.

Personal correspondence shows that these kinds of ideas were exchanged among non-medics as well. Isabella d’Este, marchioness of Mantua, assured her son Ferrante that he would have another son – according to her, the fact that his wife’s pregnancy was going so well, should be seen as an “irrefutable sign”.

Longing for a son

In Renaissance Italy, expectant parents had a clear preference for boys instead of girls. Preacher Bernardino da Feltre attributed this to the financial cost of raising and marrying off a daughter: dowries needed to be amassed, and precious clothing and jewelry needed to be purchased. “When a father hears ‘A girl has been born’ he becomes frightened and uneasy. But why? Because of these pompous clothes and vanities.” Da Feltre urged parents to stop handing out the excessive dowries that had become a custom. Women have no use of them, he says, because “virtues are great dowries” as well.

Another reason why boys were preferred, was the fact that male offspring was necessary to further the family line. This was especially important among the ruling elite. A glimpse of the anxiety this could cause can be distilled from the letters of marchioness Isabella d’Este. D’Este married Francesco II Gonzaga when she was 15 years old, had her first child at 19, and would have 8 children before she was 35.

After the birth of her first child, a daughter, D’Este is still unconcerned. When a relative congratulates her, she replies that she knows “that you, like me, would have wanted me to have a boy, as almost everyone desired”, but that they must still thank God for this daughter and be satisfied, as “it suffices that the baby girl and I are well.” During the second pregnancy, she is already more anxious, writing to her husband that she has prayed to God to grant her a little boy, “since if it should be a girl I will suffer incomparable sorrow.” When the child indeed proves to be another girl, she informs her husband of the birth in a cheerless manner:

Not to announce an event that to Your Excellency or to me will be welcome, but in order to do my duty, I inform you that now, at twenty-two and a-half hours, I have given birth to a girl. The chill that has come over me, the house, and this whole city I leave to your Excellency’s imagination.

In a letter sent a week later, she declines her husband’s offer to have a baptismal ceremony. She would rather have the child baptized at home, because “as a girl she does not merit any solemnities”.

After ten years of marriage, D’Este finally produces an heir for the Gonzaga dynasty. When her brother-in-law congratulates her, she says that she believes that he must be even happier than he says he is, as she is “very well informed of the true expectation in which you rightly awaited this joyful birth”. Joyous as it was, pressure to produce another son remained. Considering the high level of infant mortality, having more than one male heir was vital, yet in the three years after Federico was born, D’Este “only” gives birth to two more daughters. When she writes her husband to inform him of their fourth daughter, she assures him that both she and the baby girl are in good health, but says that she prefers not to expand on the subject, out of shame and unhappiness.

Five years after the birth of Federico, a second son is finally born. In a celebratory letter to the nuns of the Corpus Christi monastery in Ferrara, she thanks them for their constant prayers: “We think you in Ferrara must have been so fearful for us that you did not budge from the feet of Christ until you were certain that we had given birth to a boy. We did produce a beautiful and healthy boy, tonight at the second hour. May God be praised forever!”

How to conceive a boy

As boys were in far greater demand, it should come as no surprise that there were many medical remedies aimed at generating male instead of female offspring. In his treatise on conception, Michele Savonarola gives his readers all sorts of advice to help them conceive sons, considering that “pregnancy is welcome to all fathers, and that of a male child even more welcome than that of a female”.

As warmth plays an important part in generating males, many recommendations are aimed at increasing the temperature of the sperm and the uterus. Both men and women should eat warm foods and drink warm, easily digestible wine. For men, it was also advisable to apply warm aromatics such as musk or laudanum to the genitals. Women were encouraged to use herbal suppositories, and to avoid sitting on the cold ground.

A number of recommendations was based on the belief that boys were conceived on the right side of the uterus, and girls on the left. During sex, a pillow could be placed under the left side of the woman to help the semen reach its desired destination. According to Savonarola, this was a tried and tested method: a Venetian gentleman who already had seven daughters was told of this remedy by a physician and (without doing anything else) only had sons from that point on. Savonarola also recommended tying a string around the left testicle before sex, so that only the semen from the right, supposedly male-producing testicle is ejaculated. Pietro Bairo mentions this last method as well, adding another trick, more inspired by superstition than anything else: “tie a white bandage around your right foot for a boy, tie a black bandage around your left foot for a girl”.

Savonarola also provides some advice that might help those still in the market for a husband or spouse with male-producing potential. According to him, a fertile, male-generating man meets the following description: a strong and robust body, sanguine or choleric complexion, big testicles that produce a lot of sperm, big and wide veins, and a right testicle that deflates before the left testicle does. A fertile, male-generating woman is agile and cheerful, has a good color and a warm or temperate complexion, a subtle menstruation of good color (not too dark), a good appetite and digestion, blood that is neither to thick nor too thin, and visible veins. It is also best if she has had her first period around the age of fourteen, because this is a sign of abundance of blood and warmth.

The preference for boys in fifteenth and sixteenth century Italy was in no way exceptional. Historian Joan Cadden found the same examples of misogyny in numerous Latin medical sources ranging from the eleventh to the fourteenth centuries. She concluded that there are many recipes that tell how to have a boy or a girl, even more that simply tell how to have a boy, but none that just tell how to have a girl – girls are only mentioned secondarily. In a way, every female child was seen as a failed male child, in the medieval period. Although this did not make them useless or monstrosities, as female offspring had their own purpose, boys were clearly much preferred.

Sources:

Pietro Bairo, Secreti Medicinali (Venice: Ventura de Salvador, 1585). Trattato 25, Capitolo 5 and 6.

Michele Savonarola, Ad mulieres ferrarienses de regimine pregnantium et noviter natorumusque ad septennium (ed. by Luigi Belloni: Il trattato ginecologico-pediatrico in volgare, Milan 1952) p. 54-61.

Isabella d’Este, Lettere (trans. by Deanna Shemek, Tempe, AZ 2017) p. 62-63, 95, 98, 150, 239, 241, 262.

Bernardino da Feltre, Quaresimale (ed. by Carlo Varischi da Milano: Sermoni nella redazione di fra Bernardino Bulgarino da Brescia, 3 vols., Milan 1964) Vol. I, p. 160; Vol. III, p. 126.

Further reading:

Joan Cadden, Meanings of Sex Difference in the Middle Ages (Cambridge 1993) 133, 199, 255.

Jacqueline Musacchio, The Art and Ritual of Childbirth in Renaissance Italy (New Haven 1999).

© Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.