Farrowed futures: Prognostic pigs and pig prognostics in the Middle Ages

Could medieval pigs foretell the future? The answer may surprise you.

The medieval origins of Hen Wen, the clairvoyant pig in Disney’s The Black Cauldron

The favourite Disney film of many a medievalist is The Black Cauldron (1985). Set in an early medieval world, the movie focuses on the young 'assistant pig-keeper' Taran and his clairvoyant pig Hen Wen. At the start of the film, the little pink piglet gets hog-napped by the servants of the evil ‘Horned King’, who hopes to use the pig’s prophetic powers to locate the Black Cauldron, an ancient relic that would allow him to summon undead warriors and conquer the world. The rest of the film focuses on Taran and his attempts to save both Hen Wen and the world from the Horned King. The film is based on the first two books of Lloyd Alexander’s The Chronicles of Prydain (1964-68), who, in turn, based his stories on medieval Celtic mythology. So is Hen Wen the clairvoyant pig based on medieval analogues? This is only partly true.

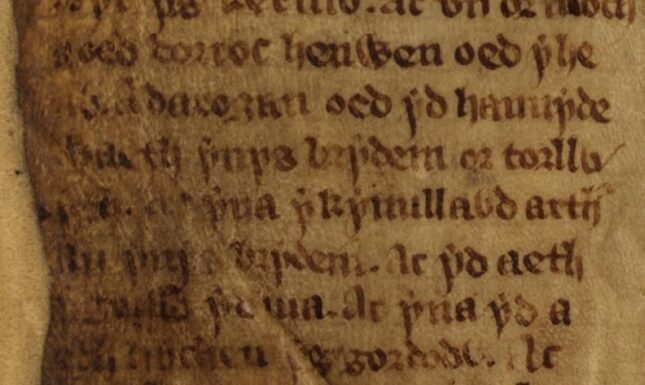

Hen Wen is based on a legendary medieval Celtic pig called Henwen [lit. ‘Old white’], which makes an appearance in the Trioedd Ynys Predein (The Welsh Triads), a medieval collection of folklore, history and mythology which survives in a number of thirteenth-century manuscripts (but the material may be centuries older). In the Trioedd, information is given in groups of three so as to aid memorisation of the information (e.g., the three ‘Red Ravagers’ of Britain are Arthur, Run and Morgant and the three ‘Stubborn Men’ are Eddilig the dwarf, Gwair and Drystan). Henwen is mentioned in the triad that describes the ‘Tri Gwrdueichyat Enys Prydein’ [Three Powerful Swineherds of the Island of Britain]. These swineherds are Pryderi, son of Pwyll, who could not to be deceived or forced by anyone; Drystan, the stubborn swineherd, who never lost a single piglet, even though Arthur, March, Cai and Bedwyr were all trying to get their hands on his pigs; and, lastly, Coll, who had a sow called Henwen. Henwen was pregnant and this did not bode well for Britain:

Ac vn o’r moch a oed dorroc, Henwen oed y henv; a darogan oed yd hanuyde waeth ynys Brydein o’r torllwyth. Ac yna y kynullavd Arthur llu Ynys Brydein, ac yd aeth y geisso y diua.

[And one of the swine was pregnant, Henwen was her name. And it was prophecied that the Island of Britain would be the worse for the womb-burden. Then Arthur assembled the army of the Island of Britain, and set out to seek to destroy her.] (ed. and trans. Bromwich 1961, pp. 47-48)

The rest of this triad narrates how Henwen escapes from Arthur’s army and gives birth to a great variety of things: a grain of wheat, a bee, a grain of barley, a wolf-cub, a young eagle and a kitten. The last three of her offspring, in particular, turn out to have negative consequences for anyone associated with them. The kitten, for instance, is thrown into the sea by the powerful swineherd Coll, but survives and grows up to become “Palug’s Cat”, one of the three ‘great oppressions of Môn’. The Henwen of the Welsh Triads, then, was not a clairvoyant pig, but a pregnant one with dark prophecies associated with her offspring.

Not-so-sweet dreams are made of pigs

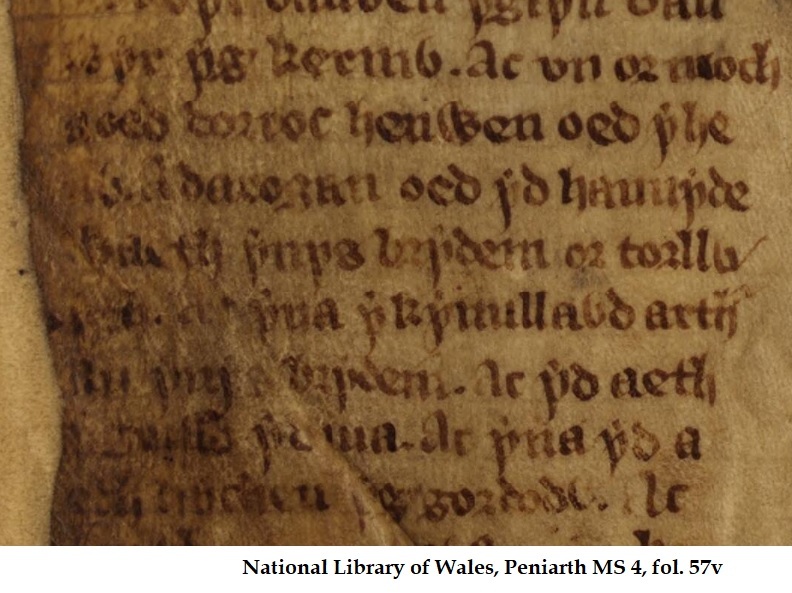

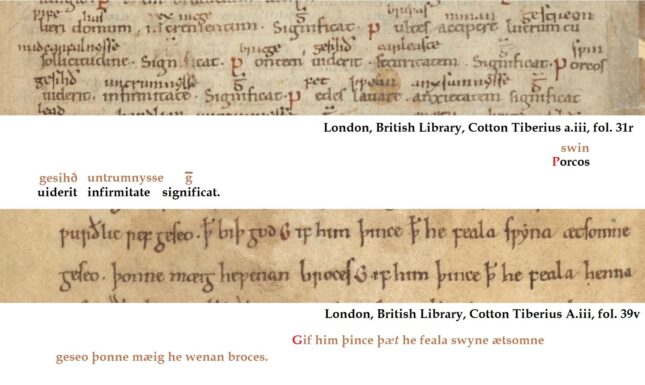

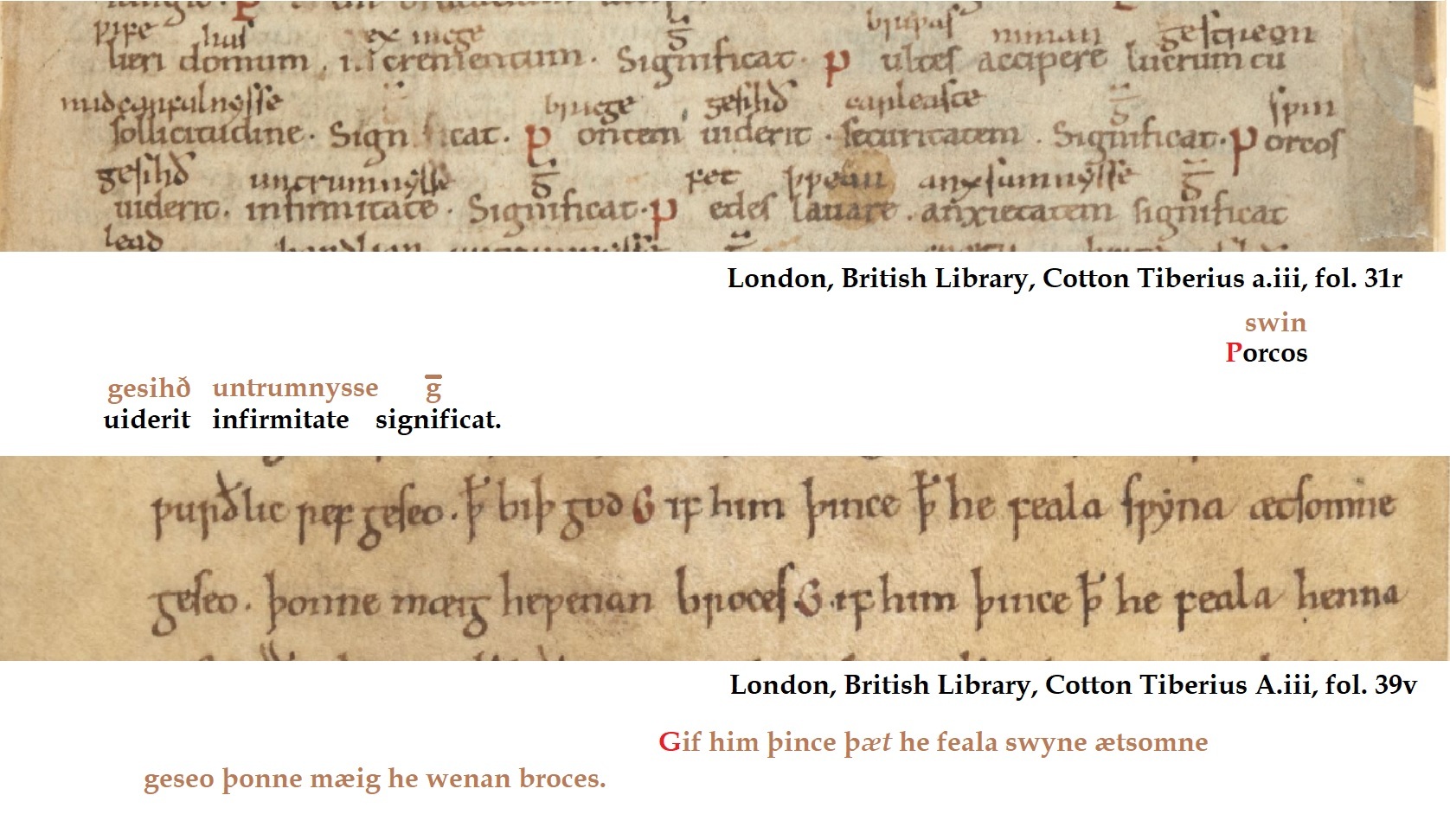

Henwen was not the only medieval pig to be associated with troubling visions of the future. This much becomes clear from two dream books in a manuscript from eleventh-century England. These dream books are part of a large body of ‘Anglo-Saxon prognostics’, short texts that outline how various things, ranging from the weather to dreams, can be used to foretell the future. Some of the dreams outlined in these texts signify a glorious future ahead for the dreamer: a dream about climbing trees indicates that you will obtain honour; washing oneself in the sea means something joyful will happen; and seeing a mouse and a lion in a dream means you will soon find safety. Other dreams may spell out your doom: wearing old shoes in your dreams is a warning for impending deception; dreaming about doves predicts sadness; and seeing the sky in flames signifies a great evil that will happen to the whole world. Two entries discuss the significance of dreaming about pigs:

If he sees pigs (in a dream), that signifies infirmity.

If it seems to him that he sees many pigs together, then he can expect adversity.

Nothing good, it seems, comes from dreaming about pigs.

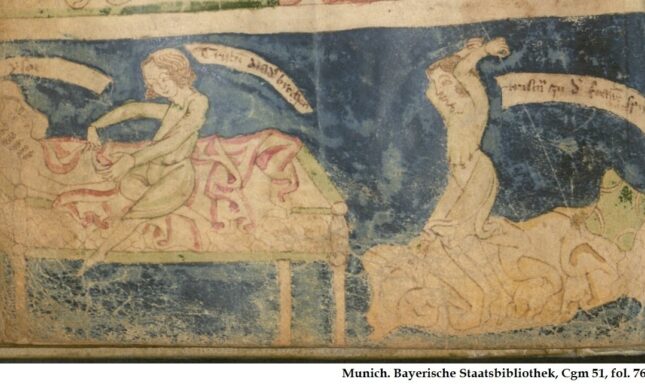

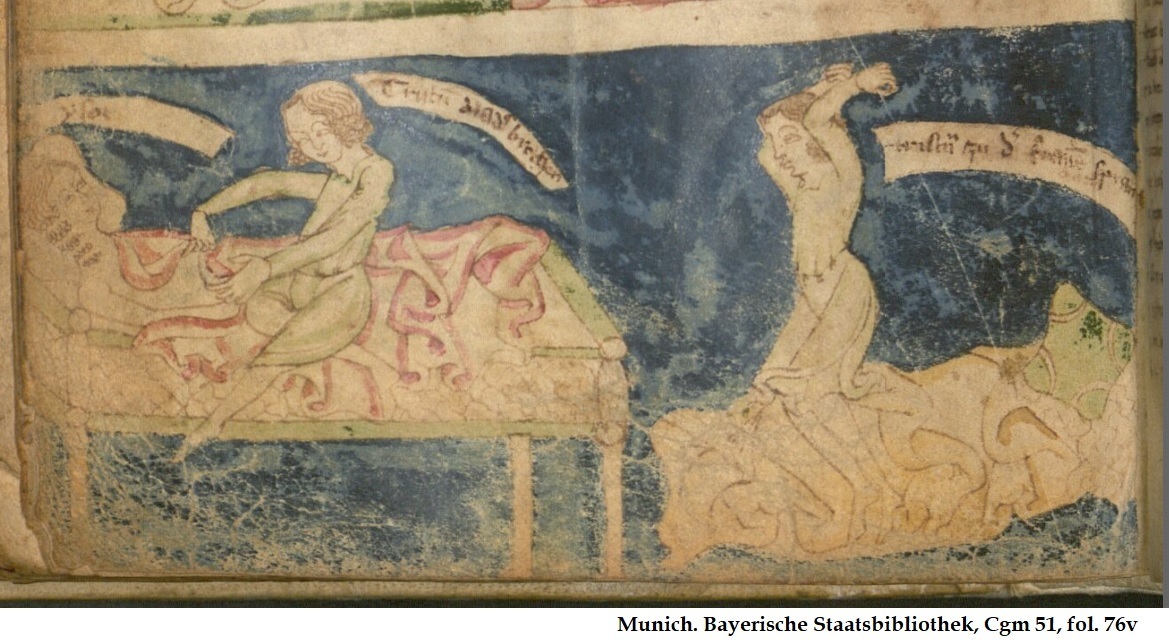

Dreams about boars fair little better. Perhaps the most famous medieval boar dream is dreamt by Marjodoc, the steward of King Mark, in Gottfried von Strassburg’s Tristan (c. 1210). In his dream, Marjodoc sees a wild boar running out of a forest, entering the King’s court and heading towards the King’s bed chamber: “Thus he plunged grunting through the Palace. Arriving at Mark’s chamber he broke in through the doors, tossed the King’s appointed bed in all directions, and fouled the royal linen with his foam.” (ch. 19, trans. A. T. Hatto 1960). Marjodoc wakes up in the middle of the night and goes in search of Tristan, only to find out that the latter, like the boar in his dream, was ‘defiling the king’s bed’ by having an affair with the Queen, Isolde. This discovery, prompted by Marjodoc's dream, sets in motion the dramatic plot of the tale which ends with King Mark discovering the adulterous lovers.

Having a near-pig experience: Prophecies from the pigsty

While dreaming about pigs can give some glimmer of the future, dreaming near pigs can be equally prognostic. In Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla (c. 1230), there are two episodes of people having prophetic dreams in a pigsty. In the ‘Saga of Halfdan the Black’, we are told that Halfdan never has any revelatory dreams until he gets some curious advice from a man called Thorleif the Wise:

Thorleif said that what he himself did, when he wanted to have any revelation by dream, was to take his sleep in a swine-sty, and then it never failed that he had dreams. The king did so, and the following dream was revealed to him. He thought he had the most beautiful hair, which was all in ringlets; some so long as to fall on the ground, some reaching to the middle of his legs, some to his knees, some to his loins or the middle of his sides, some to his neck, and some were only as knots springing from his head. These ringlets were of various colours; but one ringlet surpassed all the others in beauty, lustre, and size. This dream he told to Thorleif, who interpreted it thus: -- There should be a great posterity from him, and his descendants should rule over countries with great, but not all with equally great, honour; but one of his race should be more celebrated than all the others. It was the opinion of people that this ringlet betokened King Olaf the Saint. (source)

While this pigsty prophecy turned out well for Halfdan the Black, the same cannot be said for a similar revelation among pigs that happens in the Saga of King Olaf Trygvason. Here, one Earl Hakon is fleeing from King Olaf and hides in a cave underneath a pigsty, accompanied only by his servant Kark. Kark has a series of prophetic dreams, including one where he sees King Olaf giving him a golden ring around his neck. Kark thinks this dream will mean that he will be rewarded by Olaf, but Hakon, afraid that his servant will betray him, tells him that the dream spells out that Kark will be beheaded by Olaf. What follows in the Heimskringla is not one but two beheadings:

Then Kark cut off the earl's head, and ran away. Late in the day he came to Hlader, where he delivered the earl's head to King Olaf, and told all these circumstances of his own and Earl Hakon's doings. Olaf had him taken out and beheaded. (source)

As it turned out, for Kark, the golden ring in his pigsty dream was as valuable as ‘a gold ring in a pig’s snout’ (Prov. 11:22)!

Clairvoyant swine beyond the Middle Ages

Clearly, pigs (and their stys) were associated with prophecies in the Middle Ages (see also: The boar who would be king: Royal boar prophecies in medieval England), but I have not been able to find an actual clairvoyant pig in any medieval source. Intriguingly, the idea of pigs actually telling the future themselves appears to be a more modern phenomenon. One of Mother Goose’s nursery rhymes, for instance, links pigs to forecasting the weather:

My learned friend and neighbor, Pig,

Odds bobs and bells, and dash my wig!

‘Tis said that you the weather know:

Please tell me when the wind will bow?

This nursery rhyme is possibly based on the idea that pigs can sense a storm coming and refuse to come out of their pens prior to bad weather conditions.

An example of a more straightforwardly prognostic pig is ‘Mystic Marcus’: a ‘psychic pig’ who made a number of predictions during the Football World Cup 2018.

Mystic Marcus is but one in a line of psychic animals involved in predicting the outcome of football matches, which includes Paul the Octopus and Achilles the Cat. However, Mystic Marcus also made the news with his political predictions: he correctly divined the outcome of the Brexit referendum, the election of Donald Trump and, as recently as June 2022, he knew that the British Prime Minister Boris Johnson would resign before it had actually happened. If the medieval analogues to Mystic Marcus and Disney’s Hen Wen are anything to go by, these modern-day piggy prophecies were dark omens, indeed!

References

- Bromwich, R. (ed. and trans.). 1961. Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Welsh Triads (Cardiff: University of Wales Press)

- Hatto, A. T. (trans.). 1960. Gottfried von Strassburg: Tristan, with the 'Tristan' of Thomas (London: Penguin)

Do you want to know more about medieval pigs? You can find twelve more medieval ‘hog blogs’ here: https://www.leidenmedievalistsblog.nl/tags/medieval%20pigs

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2022. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.