Beards and Barbarians: Hair and identity in the Early Medieval West

Bushy beards, drooping moustaches and flowing hair. What does the (facial) hair of Early Medieval monarchs tell us about their identity?

Romans and Barbarians

Just like the clothes on a person’s body, head hair and facial hair gives us important cues about someone’s identity. From the clean-shaven middle class office worker, the long-haired hippy of the 60s, to the hipster with a well-kept beard, hairstyles are an important part of our personal expression and social group. For the Middle Ages, most well-known is the act of shearing, or tonsuring, the hair of clerics. But here I want to zoom in on another hairy subject: the 'Germanic' haircut of various Early Medieval rulers.

The stereotype goes that the Romans liked their hair short and their faces cleanly shaven. If not freshly shaven, a well-trimmed beard in Greek style was fashionable at some times, especially for philosophers and other learned men. Long hair, unkempt beards and moustaches, on the other hand, were often seen as a hairstyle for barbarians. For the Early Middle Ages, the arrival of long-haired kings and moustachio’d monarchs has often been seen by scholars as the replacement of the old Roman order by new Germanic invaders. But is it really that simple?

Longhaired Kings

By far the most famous for their coiffure are the Merovingian kings of Gaul (modern France), known as the ‘long-haired kings’ (reges criniti) in medieval sources. On the seal of king Childeric (fifth century), we see his hair parted in the middle and flowing down his back. According to a Byzantine historian, Agathias, it was

‘the practice of the Frankish kings never to have their hair cut… Custom has reserved this practice for royalty as a sort of distinctive badge and prerogative’ (Agathias, Historiae 1.3.4).

We know from the histories of Gregory of Tours that long hair indeed played an important role for the Merovingian family. Rival claimants to the throne were often tonsured and sent into a monastery. The act of tonsure was apparently so humiliating that the rival lost his royal aura ̶̶ At least until his hair grew back. When queen Chrodegildis was forced to choose between having her grandsons tonsured or killed, she preferred the boys dead rather than shorn (Gregory, Historiae, 3.18). Finally, the last Merovingian king (Childeric III) was deposed and then tonsured by the short-haired Carolingians who replaced him.

Seal of Childeric, copy of the original found in his tomb (now lost). Source: Wikimedia.

But if Merovingian royals wore their hair long, how did common people wear their hair? There are some clues hidden in law-texts: the Salic law considers the shearing of a puer crinitus (long-haired boy) without consent of his parents a serious offence (Lex Salica 24.2). Meanwhile, the Burgundian law code puts a hefty fine on giving a criminal or slave even so much as a wig (Liber Constitutionem 6.4), implying slaves had to remain short-haired or bald. Long hair may, therefore, have been the status signal of the freeman, although the commoner's hair would have been shorter than the royal hairdo, probably above the shoulders. Perhaps we could imagine free Frankish men wearing something of a bowl cut! Indeed, we find a very similar hairstyle on the Germanic bodyguards of the Roman emperor Theodosius on the so-called Missorium of Theodosius. If hair was an important part of expressing your social identity, then it might explain why archaeologists find so many combs in Early Medieval graves. In England, for example, bone or antler combs (often beautifully decorated) are the second most common object in cremation graves of all genders (Williams 2003:111).

Did long hair set a man apart as being of Germanic ancestry? Maybe some Romans in sixth century Gaul wore their hair long too: in Gregory of Tours we read of a merchant called Eufronius from Bordeaux who had been tonsured against his will. He fled to another town and returned only when his hair had grown back (Gregory, Historiae 7.31). Eufronius is a Roman name, but how long he actually wore his hair we will never know.

The Long-Beards

One of the Germanic peoples who lived in the Early Medieval west may even have derived their name from their magnificent beards. The Lombards in Italy were also known as Langobardi or ‘long-beards’. We find an image of one their kings, with a moustache and a long beard on the the ‘Visor of Agilulf’. This gilded bronze piece of a helmet was found close to Florence more than a hundred years ago. It shows king Agilulf (r. 591-616) seated in court, surrounded by two soldiers and approached by four men bearing gifts (some of them bearded too).

On closer inspection, the image is full of classical, Roman symbolism. The king is identified with a Latin inscription: d(ominus) n(oster) Agilu(lf) r(e)gi, 'our lord king Agilulf'. Two flying Victories flank the king, one holding a horn of plenty. The figures bearing gifts follow age-old Roman iconography showing a triumphant ruler. According to Kilerich (1997: 149), the gesture that Agilulf makes with his right hand probably symbolizes ‘the spoken word’, representing law, while the sword in his other hand represents martial skill, supposedly the two hands of Roman governance according to emperor Justinian. Thus, despite his long beard, this Lombard king is presented as a triumphant Roman ruler in this image.

Moustachio'd Monarchs

Agilulf was not the first hairy king of Early Medieval Italy. Earlier, Theoderic the Great (r. 493-526) had ruled in a Roman fashion from his capital in Ravenna. We know his likeness from the so-called 'Senigallia Medallion'. Like the Visor of Agilulf, the image bristles with the visual language of the Late Roman Empire. Theoderic wears Roman armour, carrying a winged Victory in his left hand. He is identified by the Latin inscription: Rex Theodericus Pius Princ[eps] I[nvictimus] S[emper], 'King Theoderic, ever-unconquered pious leader'. On the reverse: Rex Theodericus Victor Gentium: 'King Theoderic, conqueror of peoples'. But despite the Roman presentation, Theoderic’s curly hair and moustache have often been seen as a marker of his Germanic identity. The argument goes that if Romans wore a moustache at all, it would have been only in combination with a beard. In other words, Theoderic's moustache would have been a bold fashion statement about his Gothic heritage.

Theoderic the Great, on the Senigallia Medallion. Source: Wikimedia.

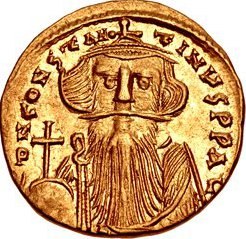

This argument has been proven wrong by J.J. Arnold (2013). In fact, throughout Roman history, we find images of Romans wearing moustaches. For example, the third century Emperor Gordian III wore a light moustache with sideburns. A mere few decades before Theoderic, the Eastern Roman emperor Marcian is also depicted with a hirsute upper lip. Constantine IV (r. 668-685) is depicted with an impressive handlebar moustache in some of his depictions.

Theoderic’s example seems to have been followed by the most famous monarch of the Early Middle Ages. When you think of Charlemagne, you might picture him as the bearded figure of later images and statues (such as in the stained glass window at the top of this page). But Charlemagne’s full beard was a later invention. Contemporary portraits are only found on coins, and here we find Charlemagne portraying himself as a Roman emperor: dressed in a toga, a diadem on his short-haired head, and a triumphant inscription declaring him emperor. But what do we see? Perched on his upper lip is a moustache. Charlemagne may have started a trend: his grandchildren Lothar I and Charles the Bald also wore moustaches.

The Symbolism of Hair

My personal favourite Early Medieval beard belongs to another Roman emperor from Constantinople. Herakleios Konstantinos Pogonatos (r. 630-668), ‘Constans the Bearded’, is shown with a long, pointy moustache and an incredibly long beard that puts most beards to shame. Constans II reminds us that for the Early Middle Ages, we cannot make a simple opposition of barbarian beards versus clean-shaven Romans anymore, itself a relic of Imperial Roman propaganda. If Theoderic’s moustache or Agilulf’s beard was a statement of their Germanic heritage at all, it blended seamlessly with Roman imagery of rulership.

Many scholars have seen beards and long hair as the remnant of some kind of ancient Germanic tradition. But by the sixth century, another more important point of reference would have been Christianity. Kings and commoners alike would have been influenced by the story of long-haired Samson and his legendary strength from the Old Testament. Similarly, the church fathers had thought of beards as masculine and strong (Wood 2018: 112).

To conclude, the symbolism of male hair was a lot fuzzier than often thought. While hair may have expressed a Germanic heritage in some cases, it would not have contradicted the otherwise 'Roman' ambitions of these monarchs. Men might have worn their drooping moustaches, flowing hair and pointed beards not as some kind of statement about their Germanic identity, but in reference to the Old Testament, as a fashion statement, as a sign of their social status (freeman or king), or as a statement of their strength and manliness.

Emperor Constans II the Bearded. Source: Wikimedia.

Further Reading

Jonathan J. Arnold, 'Theoderic's invincible moustache', Journal of Late Antiquity 6.1 (2013) 152-183.

Paul Edward Dutton, Charlemagne’s Mustache and Other Cultural Clusters of a Dark Age (New York 2004) 3-42.

Bente Kilerich, ‘The Visor of Agilulf: Langobard Ambitions in Romano-Byzantine Guise’, Acta Archaeologica 68 (1997) 139-151.

Ian Wood, ‘Hair and Beards in the Early Medieval West’, Al-Masaq 30.1 (2018) 107-116.

© Jip Barreveld and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jip Barreveld and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.