Writing your own Beowulf: A creative response to an early medieval poem

What happens when a student writes an Old English poem inspired by an early medieval epic?

{{Introduction by Rachel A. Fletcher: The following post is a contribution by MA student Sophie Koster. She has recently completed the course "Beowulf and Beyond: An Early Medieval Poem and Its Modern Adaptations", in which students examined the Old English epic poem Beowulf and its legacy in novels, films, TV, stage and more.

To learn more about what goes into retelling a medieval poem in a new context, students on the course had the chance to write their own creative response to Beowulf, accompanied by their reflections on the process. Here, Sophie shares her own Old English poem, "Þæt bið gōd cyning!", and discusses how writing it helped her to reflect on the themes of Beowulf.}}

Þæt bið gōd cyning!

Iċ mǣte of līfe of lofe 7 of dōme

Iċ mǣte of cyningum 7 of dracum

Iċ mǣte of æl-wihtum 7 hira yfela earma

Iċ mǣte of þīn strengþe þā þū him ofslēa.

Ac iċ sēo hira mōdru

Wīf þe forluron hira suna

Wīf þe, ġeliċe mē, brucon unweorþlīcra sige-galdra 7 him wæs ġēomor sefa

Wyrd þē stalode geong in geardum

Iċ wysce þæt þis sārspell þīn līfes wǣre

Mīn sunu

Mīn Bēowulf.

Translation: That will be a good king!

I dream of life, praise and glory

I dream of kings and dragons

I dream of monsters and their evil arms

I dream of your strength when you kill them.

But I see their mothers

Women who lost their son

Women who, like me, used useless charms for victory, and theirs was a sad mind

Fate took you, young in the yard

I wish this grievous story were your life

My son

My Beowulf.

This short piece of poetry was inspired by one of the best-known works from the Old English literary tradition: Beowulf. This poem presents the epic tale from the point of view of Beowulf’s mother. In this poem, Beowulf is not a story of the adventures of a Scandinavian hero, but a dream of a mother who lost her infant son. She fabricates a story of what her son’s life could have been. She dreams of him growing into adulthood as a fierce warrior, slaying monsters and becoming king. Yet, while dreaming of his victory and glory, she thinks of the monsters’ mothers. She thinks of women who, like herself, must live with the grief of a lost child. Beowulf has become a way for a mother to deal with her sorrow.

Though being the primary source of inspiration, Beowulf is not the only work that has left a mark. The Old English work, The Dream of the Rood, has also left a dreamy trace. In the following paragraphs, I will show how both Beowulf and The Dream of the Rood inspired this short poem. Lastly, I will explain why I chose to write the poem in Old English.

Beowulf and Motherhood

Motherhood might not be the first concept that comes to mind when reading an epic poem about superhuman Scandinavians, malicious monsters and fierce firedrakes. Yet, when we dive into the deep and dark marshes of the story, we meet a monstrously maternal figure: Grendel’s mother.

In Beowulf, the protagonist defeats Grendel by ripping off his arm and thus obtains glory at the cost of the monster’s life. Fatally wounded, Grendel returns to the marshes where death claims him. After seeing her son die, Grendel’s mother stalks to Heorot to attack the Danes as payment for her dead child. Her act of vengeance has often been read as a reflection of the Germanic notion of wergild, which demands payment after the murder of a relative. But, this act of revenge is also an expression of emotionality. As described by Trilling in her article: “Her attack on the Danes is not monstrous in the same way that Grendel’s is, but rather motivated by sadness and anger at the murder of her son” (Trilling 7). This rueful revenge expresses her grief for the loss of her child and it gives Beowulf’s heroic act of monster-slaying a bitter aftertaste.

Drawing on the moral complexity of monster-killing and maternal reactions to losing a child, I presented Beowulf’s mother as reflecting critically on her self-fabricated story. She dreams about her son’s superpowers as a monster-slayer. She dreams of “æl-wihtum 7 hira yfela earma”(l.3) and how her son rids the world of these foul creatures: “Iċ mǣte of þīn strengþe þā þū him ofslēa.” (l.4). She wishes her child had lived a life of lof 7 dom, but she realises this would mean creating a fate for other mothers similar to her own: “Ac iċ sēo hira mōdru / Wīf þe forluron hira suna.” (ll.5-6). In her dream, she presents glory not as an abstract concept, but as something that can only be obtained through the loss of a mother’s child.

Ruefulness and the Rood

My poem suggests that Beowulf was never realised as a complete epic poem. Instead, it suggests that Beowulf is a dream vision, created by a mother to deal with her grief. Presenting the story as a dream is (sadly) not my creative invention. Cooking up stories as a dream vision is used in another Old English work: The Dream of the Rood.

The Dream of the Rood starts with an unnamed speaker who dreams about a bejewelled tree. Right before his eyes, the sparkling tree transforms into the cross on which Jesus was crucified. The rood starts to speak and it tells the Dreamer of the Passion of Christ and how “wēop eal gesceaft” [all creation wept] (l.55). As you might have guessed, the general tenor of the poem is a sorrowful one. The poem captures this sad mood exceptionally well with the word: “sorhlēoð” [sorrowful song] (l.67), which is used to describe the song of those who lowered Jesus from the cross. Interestingly, this word also makes an appearance in Beowulf when it describes the grief of a father who lost his son: “sorhlēoð gæleð / ān æfter ānum” [[he] chants a song of sorrow, one after another] (ll.2460-1). This connection, though established by only a single word, inspired me to implement themes from the Dream of the Rood in the poem of Beowulf’s mother.

Just like the Dreamer in The Dream of the Rood, Beowulf’s mother is an unnamed figure who dreams of the loss of a loved figure. However, whereas the Dreamer dreams of a story that has already happened, Beowulf‘s mother envisions an impossible future. In this way, she not only loses her son, but she also loses the heroic life she imagined for him: “Iċ wysce þæt þis sārspell þīn līfes wǣre.” (l.9). This double loss gives her story a deeply sorrowful mood, which makes her tale similar to the sorhlēoð in the Dream of the Rood and Beowulf. She laments the loss of a son. Just like those who lowered God’s Son from the cross, and like the father who grieves the loss of his child in Beowulf.

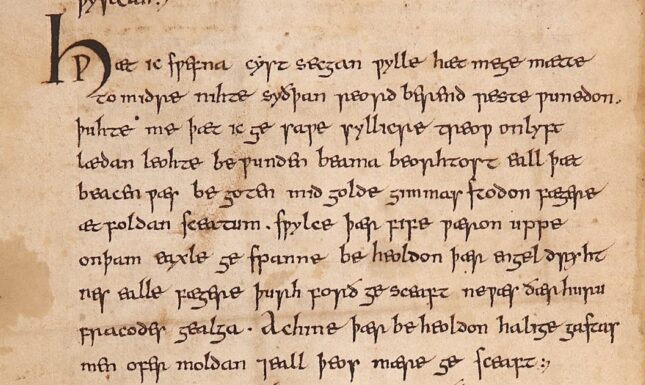

New Old English

Old English is not a simple language to learn. The word order can be nearly as flexible as Latin and it has just as many cases as modern-day German. If translating from Old English to modern English is already such an ungodly ordeal, why on earth would you want to translate the other way around? First of all, because it’s a lot of fun! It makes you appreciate the Old English Beowulf more because you learn to understand the language not only from past to present but also from modern to medieval times. Browsing through encyclopaedias, dictionaries and your source text in search of the right words figuratively transports you to the scriptorium of an early medieval English monastery. It makes your connection to the text you are studying a lot stronger.

Also, translating into Old English is a great didactic exercise, especially when revising Old English grammar. You can learn a lot from textbooks on Old English grammar. But, what better way is there to learn a grammatical system than by using it yourself? Rafael J. Pascual mentions this didactic benefit in a chapter on composing neo-Old English verse: “Experience tells us (and it receives ample support from numerous studies in the field of second-language acquisition) that learners learn best through creative interaction with their objects of study” (Pascual, 210). Studying Old English to create can make you more engaged in the process as you transform from a reader into a scribe. Interacting creatively with the Old English Beowulf motivates me, and perhaps you as well, to learn more about the poem and the pleasantly difficult realm of Old English linguistics.

Translating into Old English is amazingly complex, yet rewarding work. It strengthens the bond between the student and the source text, even if separated by more than a millennium. Furthermore, interacting with the literary aspect of the text can inspire students to dive deeper into its linguistic aspect. Aiming to heed Pascual’s didactic advice, I translated my poem into the language of Beowulf. Even though I checked my poem diligently, it might still contain some errors. But let’s not forget that even the scribes of Beowulf make errors! (For more information on scribal errors in Beowulf, I recommend Leonard Neidorf’s article on scribal errors in the Beowulf manuscript).

Conclusion

Interacting creatively with Beowulf is both fun and instructional. The subject of my short poem was inspired by the grievous act of vengeance of Grendel’s mother after her son had been murdered. The poem presents a complex connection between glory and monster-slaying. This complex relationship motivated me to think about it critically and inspired me to infuse it into my short poem.

The Dream of the Rood inspired me to present Beowulf as a dream vision and give it a sorrowful mood. In my poem, the dream functions not as an experience of the unconscious, but as an imagined situation that can never occur. This makes the sadness of the poem even more powerful and it transforms Beowulf from a heroic tale to a sorhlēoð of loss.

Lastly, making Beowulf ‘fanfiction’ allowed me to go beyond the literary aspect of the text and dive deeper into its linguistic aspect. Translating my short poem into Old English strengthened the connection between the Old English Beowulf and myself. Also, interacting with Old English, instead of just reading, is an engaging and fun way of learning!

If you asked me what the best way is to study Beowulf, I would chant (not as a sorhlēoð): “wyrc!” [create!]

Works cited list

Primary sources

- Beowulf. Edited by George Jack. In Beowulf: A Student Edition, 27-211. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- The Dream of the Rood. Edited by Richard North, Joe Allard and Patricia Gillies. In The Longman Anthology of Old English, Old Icelandic and Anglo-Norman Literatures, 283-294. New York: Routledge, 2011.

Secondary sources

- Hawtree, Richard. “Sorhleoð Galan: A Note on the ‘Sorrowful Song’ for Christ in the Dream of the Rood.” Notes and Queries 69 (2022): 177-184.

- Neidorf, Leonard. “Scribal Errors of Proper Names in the Beowulf Manuscript.” Anglo-Saxon England 42 (2013), 249-269.

- Pascual, Rafael J. “The Fall of the King and the Composition of Neo-Old English Verse.” In Old English Medievalism, edited by Rachel A. Fletcher, Thijs Porck and Oliver M. Traxel, 209-222. Boydell & Brewer, 2022.

- Trilling, Renée Rebecca. “Beyond Abjection: The Problem with Grendel’s Mother Again.” Parergon 24 (2007): 1-20.

- AI images: https://designer.microsoft.com...;

© Sophie Koster and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Sophie Koster and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.