The Rise of Poetry Therapy in Eleventh Century China

How did literati manage their mental health in middle period China? Melancholy, depression, and down moods were as common among them as among us today. In the absence of antidepressants and therapists, how did they get out of low spirits and regain mental balance?

In studies of eleventh century China, scholars have delineated the contours of health care. Little, however, is known about mental care in this period. In a book project started a decade ago, using the case of Su Shi’s 蘇軾 (1037-1101) invention of poetry therapy, I hope to make a start filling this gap. This blog presents a sneak preview.

A traumatic life

Su Shi’s life was full of drama. He began his career rather smoothly. In 1057, at mere twenty, he passed the civil service examination with high distinction, becoming known overnight. This was a time when the intellectual and political mainstream encouraged literati to be independent-minded and dare to speak truth to power, including the monarch.

Ten years later, however, the political tide began turning. In 1067, Shenzong 神宗 (1048-85), an ambitious and capable monarch took the throne. Unhappy with how powerful the literati had become the previous decade, he commissioned Wang Anshi 王安石 (1021-1086) to spearhead a sweeping reform designed to recentralize moral authority to the monarch, thereby to unify morality. This was the great eleventh century reform that still divides scholarly views today.

Since the reform was launched in 1069, Su Shi, deeply committed to moral individualism, began opposing it in various ways. When persuading Shenzong to change his mind proved futile, Su, unable to hold his tongue, kept criticizing the reform in his prose and poetry. These short pieces, full of wit and humor, went viral, turning Su Shi into a celebrity public opinion leader. This, of course, made him an obvious target.

In 1079, as part of Shenzong’s efforts to increase his authority, Su Shi got arrested, under the charge of slandering court policy. Following four months in jail, during which he was flogged and interrogated, Su was exiled to Huangzhou 黃州, in today’s Hubei province, where he lived for more than four years. In 1085, with Shenzong’s death, the political tide turned back against the reform. Su got rapidly promoted and took up prominent positions in and out of the court. In this ideologically favorable but nonetheless dangerous political world, Su’s independent stance and outspokenness still kept getting himself into trouble at times. In 1093, Shenzong’s son Zhezong 哲宗 (1076-1100) began ruling in person. Determined to carry forward his father’s unfinished enterprise, he stepped up removing dissidence. Su Shi was soon exiled a second time, to the far south – Huizhou 惠州, in today’s Guangdong Province. In 1097, with tightening political atmosphere, Su was exiled a third time, to the southern tip of the Song state – Danzhou 儋州, on today’s Hainan Island, where he lived till 1100.

These twists and turns did not change Su’s mind – he kept upholding his principles throughout his life and would not go against what he thought was the right thing to do. But surviving the jailing experience and three exiles, each time harsher, took a toll on his psyche. Take the third and last exile for example. At its beginning, Su thought he would not live long in the place of miasma. His writings during the early days there were filled with death images. Two and a half years later, however, Su completed a major scholarly project – a set of three classical commentaries where he formulated his political philosophy systematically, as an alternative to the one guiding the reform, for when the reform regime shall fall on its own – Su firmly believed that making everyone have the same morality would not work for long. How did Su Shi get out of low points in his life and stay resilient?

Among the measures he took, some were conventional, like meditation, healthy diet, and building up local support networks. One method he claimed was his invention. This was writing poems after those by Tao Qian 陶潛 (c. 365-c. 427, courtesy name Yuanming), using the same rhyming words – what is called “rhyming-Tao poems” (he Tao shi 和陶詩). When exiled to Danzhou, Su did not bring much luggage. Among what little he carried, there was a Tao Yuanming Anthology. As for why, he told a friend: “diverting myself from being depressed precisely relies on this.” 陶寫伊鬱, 正賴此爾. [1] How can Tao’s poems have such a healing effect for Su?

Discovering the therapeutic appeal of Tao Qian’s poems

In Chinese culture, Tao Qian is regarded as the icon for recluse poetry. Born of an elite family, Tao chose to quit serving in the government, returning to a farmstead life, what he considered closer to his heart. Living the consequences of his choice, however, proved a challenge. Indeed, Tao seemed forever struggling with the dilemma between living freely but poorly and working in the government but unhappily. Besides resorting to alcohol, Tao dealt with such struggles with poetry.

Today, many think Tao was a great poet, due to the inherent literary quality of his poems. To Su Shi, however, the appeal of Tao’s poems lied elsewhere. As he told us: Tao’s poems “look plain yet are actually lustrous, emaciated yet are actually plump” 質而實绮、癯而實腴; [2] they “are haggard outside but full of fat inside; look bland but are actually delicious” 外枯而中膏,似澹而實美. [3] In each comment, Su used a character containing a radical referring to “fat”: “yu” 腴 and “gao” 膏 – as if Tao’s poems are a kind of high-protein meat full of nutrients supplying what his body needs. Why so? Let us take a look at a poem of Tao’s that Su particularly liked, to see what he meant. This is the ninth of a series of twenty poems titled “Drinking Alcohol”. [4]

清晨聞扣門 |

On early morning, I heard a knock on the door; |

倒裳自往開 |

Pulling on my clothes upside down, I went to open it myself. |

問子為誰與 |

I asked: “Who, Mister, are you?” |

田父有好懷 |

“An old farmer, with good intentions.” |

壺漿遠見候 |

With a jar of acidish drink he had come far to visit me, |

疑我與時乖 |

Suspecting I am at odds with the times. |

襤縷茅檐下 |

“In edgeless and patched clothes under thatched eaves, |

未足為高棲 |

It is not worth loftily lodging. |

一世皆尚同 |

The whole world adores sameness; |

願君汩其泥 |

I wish you would mingle with the mud.” |

深感父老言 |

“I feel deeply grateful for your words, elder; |

稟氣寡所諧 |

But my inborn temperament has little in harmony with it. |

紆轡誠可學 |

Turning the bridle can truly be learned; |

違己誰非迷 |

Yet going against oneself, who would not get lost? |

且共歡此飲 |

Let us just enjoy this drink together – |

吾駕不可囘 |

My horse cannot be turned around.” |

On the face of it, this poem looked rather plain: Tao gave an account of an exchange he had with an old famer visitor, in which he asserted his determination to stay true to himself. If we give it more thought, however – the early morning knock was unlikely something that took place in Tao’s social life. It is illuminating to read the first two lines against these verses from the Classic of Poetry 詩經:

東方未明 |

The east has not yet dawned; |

顛倒衣裳 |

Upside down the clothes were pulled on. |

顛之倒之 |

Upside down and in reverse, |

自公召之 |

From the duke came the summon. [5] |

The same early morning, the same pulling on clothes upside down. This tells us that instead of accounting for what had happened on a particular morning, Tao Qian was writing about his psychic life. In particular, it was about the topic that appeared in the last line above: the allure of working in the government, with all the benefits that come with it, in contrast with his living true to himself but in poverty.

Furthermore, if we compare Tao’s mental state in the beginning of his poem with that in the end, we can see there is a psychological movement within the poem: at first Tao’s mental peace was disturbed – he rose up hastily in reaction to the knock on the door. From our contextual reading, this knock was symbolizing a summon to the government. Then, through the words he put in the mouth of the old farmer, Tao went on to weigh the two options of serving and withdrawal. By the last line, however, the wavering was gone – Tao came to hold fast the choice he has made, without a doubt.

This, in other words, is a poem in which Tao did his psychological consolation, through which he handled the hesitation that popped up when living the consequences of his choice. And such poems Tao wrote a lot, about the same topic over and over again spanning decades. It was this quality of Tao’s poems that Su Shi found appealing. Other than sharing Tao’s temperament – Su was equally stubbornly at odds with the world, Su discovered Tao’s poems had therapeutic efficacy under their lackluster appearance. This made simply reading Tao’s poems helpful, as Su told us: “Whenever not well in my body, I would fetch [Tao Yuanming Anthology] to read – no more than one piece [at a time], for I fear that after having read it all, I would have nothing to divert myself with.” 每體中不佳,輒取讀,不過一篇,惟恐讀盡,後無以自遣耳. [6]

Writing rhyming-Tao poems as therapy

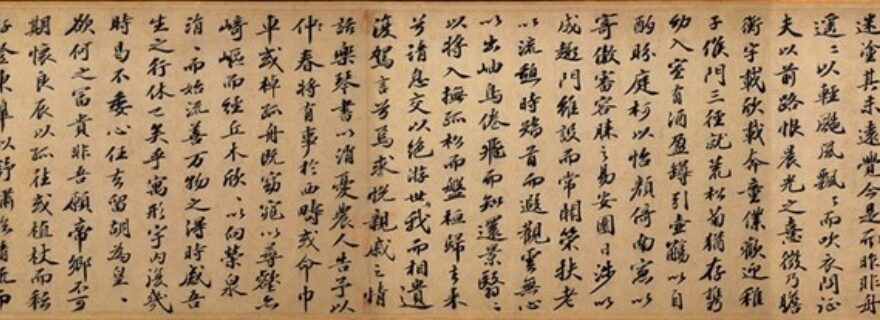

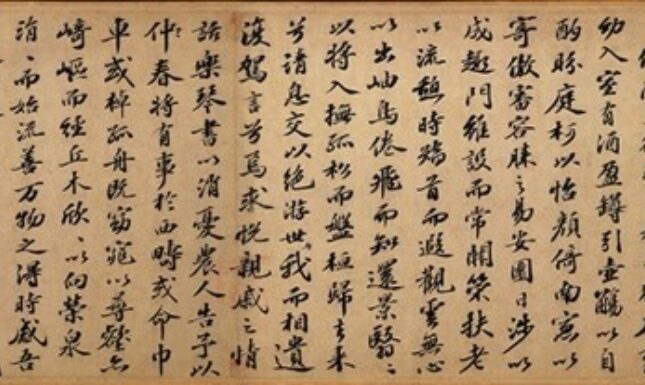

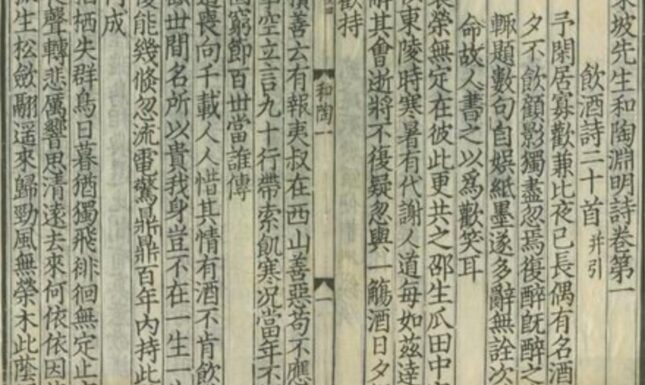

Su Shi began using reading Tao’s poems to make himself feel better during his first exile.[7] Over the years, he also found many other ways to use Tao’s poems, like calligraphing them, as shown in the first image. In the 1090s, he began writing rhyming-Tao poems. During his second exile, Su made it a self-conscious project, wanting to write such a poem after all of Tao’s poems. At the beginning of his third exile, Su wrote rhyming-Tao poems intensely, showing a preference for long series consisting of multiple poems. It was partly through this, that he regained his mental balance, turning to pick up the classical commentary project and see through to its completion. In late 1097, Su put together the 100+ rhyming-Tao poems he had written, seeking to get them published. They were eventually put to print in the early twelfth century.

A striking presence in Su’s oeuvre, these rhyming-Tao poems have been studied by many scholars. Most, however, either approach them from a literary perspective, or nonetheless focus on the content of individual poems. In the Song edition of Su Shi’s Collection of Rhyming-Tao Poems that passed down to us, however, poems were often grouped by series, even when there was no such in Tao’s anthology.

When we study these poems by inquiring how Su used this writing practice to make himself feel better at down moments and following the original layout arranged by Su himself, it becomes clear he used writing rhyming-Tao poems as therapy. A dejected exile, Su found it of therapeutic efficacy to keep himself immersed in the world created by Tao’s poems. Reading them and writing poems using Tao’s rhyming words helped Su feel the presence and support of his brother-in-arms and fellow patient, when he was paying the price for unswervingly staying true to himself in the protean world of politics. As one of Su’s friends told us:

子瞻謫嶺南 |

When Zizhan (Su Shi’s style name) was demoted to south of the Five Ridges, |

時宰欲殺之 |

The grand councilors then wanted to kill him. |

飽吃惠州飯 |

Heartily he ate Huizhou meals, |

細和淵明詩 |

Meticulously he rhymed [Tao] Yuanming’s poems. [8] |

Compared with the classical commentary project, what he considered the consummation of his lifetime’s learning, writing rhyming-Tao poems was a means to cope. Su used the latter to gain what it took to pull himself together and finish the former.

Writing rhyming-Tao poems did not begin with Su Shi, but it was through his intervention that it became a widely used therapy. Many late Northern Song literati, similarly caught in the conundrum of staying true to themselves and serving in a government that did not allow independent opinions, found it handy to take it up, following the example of their leader Su Shi.

*

Notes

[1] Su Shi, Su Shi wenji, 1626.

[2] Su Shi, Su Shi shiji, 1881.

[3] Su Shi, Su Shi wenji, 2109.

[4] Lu Qinli anno., Tao Yuanming ji, 91-92.

[5] Mao, Zheng, and Kong, Maoshi Zhengyi, 394–95.

[6] Su Shi, Su Shi wenji, 2091.

[7] Su Shi, Su Shi wenji, 2206.

[8] Huang Tingjian, Huang Tingjian quanji, 1059.

Sources

Huang, Tingjin 黃庭堅. Huang Tingjian quanji 黃庭堅全集. Jiangxi renmin chubanshe, 2011.

Lu Qinli collated and annotated, Tao Yuanming ji 陶淵明集. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1979.

Mao, Heng, Zheng Xuan, and Kong Yingda. Maoshi zhengyi 毛詩正義. Beijing: Beijing daxue chubanshe, 2000.

Su, Shi. Su Shi wenji 蘇軾文集. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1986.

———. Su Shi shiji 蘇軾詩集. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1982.

———. Ying Song Dongpo Xiansheng he Tao Yuanming shi 景宋東坡先生和陶淵明詩. Tianjin: Tianjin guji chubanshe, 2015.

Further reading

Davis, A.R. “Su Shih’s ‘Following the Rhymes of T’ao Y’üan-ming’ Poems: A Literary or a Psychological Phenomenon?” Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia 10, no. 1 & 2 (1973): 93–108.

Hightower, James R. The Poetry of T’ao Ch’ien. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970.

Nylan, Michael. The Chinese Pleasure Book. New York: Zone Books, 2018.

Owen, Stephen. “The Self’s Perfect Mirror: Poetry as Autobiography.” In The Vitality of the Lyric Voice, 71–102. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986.

Swartz, Wendy. Reading Tao Yuanming: Shifting Paradigms of Historical Reception (427-1900). Cambridge (Mass.) and London: Harvard University Asia Center, 2008.

Yang, Vincent. “A Comparative Study of Su Shi’s He Tao Shi.” Monumenta Serica 56 (2008): 219–58.

Yang, Zhiyi. Dialectics of Spontaneity: The Aesthetics and Ethics of Su Shi (1037-1101) in Poetry. Brill, 2015.

© Jiyan Ilbrink and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jiyan Ilbrink and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.