The Most Widely Read Middle Dutch Book: An Introduction to 'Pages of Prayer'

The years 1383-84 mark an event that would cause a cultural earthquake: Geert Grote translated the Book of Hours into the Dutch vernacular. How to research the many extant 'pages of prayer' that testify to the popularity of his translation?

This is a key question that lies at the heart of the ERC-funded research project ‘Pages of Prayer: The Ecosystem of Vernacular Prayer Books in the Late Medieval Low Countries, c. 1380-1550 [PRAYER]’ of which I am the Principal Investigator (PI). The five-year project commenced on 1 March 2023 and sets out to conduct a first large-scale investigation of what is a unique corpus of prayer books as well as the largest corpus of manuscripts and printed books in Middle Dutch. Grote’s translation not only became a determining factor in devotional culture, but also proved to have a great influence on Middle Dutch literature, as well as on book production in the late medieval Low Countries. Scribes, printers, patrons, readers, texts, images, devotions as well as the books themselves created, shaped, and sustained a complex web of interconnections that can best be viewed as an ecosystem. ‘Pages of Prayer’ develops a new approach – network philology – that aims to study all these aspects in their mutual interdependence.

The Origins of Grote’s Translation

Geert Grote, the founder of one of the period’s most powerful religious reform movements, the Modern Devotion, allegedly translated several texts that make up the Book of Hours into the Dutch vernacular when he was in his early forties. At that age he already had quite a life behind him. When he was around the age of ten, his parents died in a plague epidemic. After an education at the University of Paris, he was given posts as canon at the cathedrals of Utrecht and Aachen. A glittering career lay ahead. But a serious illness in 1374 made him realize that he had to completely turn his life around. He made his house in Deventer available to poor women who wanted to pursue a pious life and for a time he withdrew to a Carthusian monastery near Arnhem.

From 1379 Grote traveled and preached his newly acquired insights: people should leave their sinful way of life behind and, following the example of the apostles, pursue an internalized faith that is focused on the life of Christ. In the second half of 1383 he was silenced: the Bishop of Utrecht issued a ban on preaching by deacons and thus also deprived Grote, who had only been ordained as a deacon, of the opportunity to publicly criticize abuses within the Church.

Grote now had to resort to the written word to spread and effectuate his ideals. He used what would become the final years of his life (on August 20, 1384, he too would die of the plague during an epidemic) to translate the texts of the Book of Hours (i.e., the series of psalms, hymns, lessons from the Bible, and prayers to be read on a day at eight different times; ‘hours’ can also refer to the eight moments of prayer: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, Nones, Vespers and Complines) into his mother tongue. However, we are only informed about his ‘translatorship’ through later accounts of his four biographers, all affiliated with the Modern Devotion, including Thomas a Kempis. Their statements do not show complete consensus regarding the texts he translated, but they indicate that Grote translated more than what are now considered the ‘core’ texts of a Books of Hours (the Hours of the Virgin, Penitential Psalms, Litany of Saints, and the Vigil of the Dead). All four authors mention the Hours of the Virgin (Fig. 1), three mention the Penitential Psalms and the Vigil of the Dead, two mention the Hours of the Holy Spirit. Both the translations of Hours of the Holy Cross and the Hours of the Eternal Wisdom are mentioned by but one biographer apiece. Two biographers leave room for speculation by referring to other, unspecified, Hours and texts.

Grote presumably made the translation of the Hours for the poor women who had been living in his house in Deventer for just under ten years at that time. But Grote, as an itinerant preacher, will undoubtedly also have met lay people whose spiritual life would have benefited from a Book of Hours in the vernacular. It is also quite possible that Grote translated the Hours at the request of these lay people – citizens who felt drawn to Grote’s ideals and supported the Modern Devout. (Desplenter, 'Het getijdengebed in het Nederlands').

Larger Corpus = Less Research?

What is certain is that the Book of Hours in Grote’s translation would become the most widely used Middle Dutch book of the late medieval Low Countries: at least some 850 manuscripts are now preserved in libraries, archives, and private collections, and from 1480 onward the Book of Hours appeared in print as well (ca. 30 editions before 1540, Fig. 2). In his influential overview, Frits van Oostrom has highlighted Grote’s Book of Hours as the masterpiece (‘topstuk’) of the Modern Devotion that found its way into many a godly home – for centuries, he claims, people prayed in Dutch in the words of Geert Grote (Wereld in Woorden, pp. 492 and 495).

Nevertheless, the words and books that readers would have used daily have been left largely unexamined. Art historians have done excellent work on the more lavishly illuminated specimens, but the books in which the Hours are contained have only rarely been studied specifically for their texts, leaving the ‘masterpiece’ largely unexplored. The high numbers of manuscripts are often put forward as problematic: they make it virtually impossible to create an edition according to current scholarly standards (Van Oostrom, Wereld in Woorden, p. 492). Another reason might be that since the 1940 edition by van Wijk the content of the Book of Hours of Geert Grote has been viewed as established and the texts as fixed.

Beyond the Books of Hours

‘Pages of Prayer’ does not aim to recover Grote’s original text. Rather, the project asks pertinent questions about the role of the translation in – and impact on – late medieval religion, culture, and society: How did Dutch-language prayer books and their function evolve throughout the fifteenth century, the period of the Medienwechsel, and the early Reformation? What patterns can we entangle in the compilations of texts and images found in these books and how do they relate to their function(s)?

As with Grote’s biographers’ statements, the contents of manuscript and printed Books of Hours fluctuate. Many books contain a selection of the abovementioned texts, and often they comprise various other texts, such as prayers, meditative treatises, and spiritual exercises. In the wake of the popularity of Grote’s translations of the Hours, numerous other devotional texts gained popularity and were disseminated in hundreds of manuscripts and printed books. Not only does the label ‘Book of Hours (of Geert Grote)’ conflate many kinds of texts and types of prayer books into one, but it also becomes clear that the transmission and function of the texts contained in these books are intricately connected. To study a single text in isolation would mean that we lose sight of the context in which it functioned and flourished.

To allow for a broader, inclusive view, ‘Pages of Prayer’ does not focus strictly on Books of Hours (books that contain at least the ‘core texts’ of a Book of Hours), but also includes any book that features one of texts believed to be translated by Grote. This inclusive definition permits us to for example include a ‘prayer book’ that was owned by the Leiden secretary Jan Filipszoon (Fig. 3). Apart from the Short Hours of the Cross – in this case intriguingly interwoven with another Hours text (the Our Lord’s Crown of Thorns) – this manuscript, made in the early 1480s, contains a collection of prayers, treatises, and lists, like the ‘Six points required for a devout person’.

Network Philology

To answer questions about the function of prayer books and their role in society, ‘Pages of Prayer’ develops a cross-disciplinary approach: network philology. This approach draws on ideas from material philology, social network analysis, the bringing together of text and image in an analysis of a shared devotional culture and practice, and Bruno Latour’s Actor Network Theory (ANT), and aims to integrate all relevant aspects of what we might call the prayer book-ecosystem: i.e., the materiality of the book as well as the texts and images contained in a book, its producers, owners, readers, and their use and reception of the book. To bring all these aspects together and map their relationships, ‘Pages of Prayer’ starts by building a custom-made database that will allow for network visualisations and an explorative analysis of the prayer book-ecosystem.

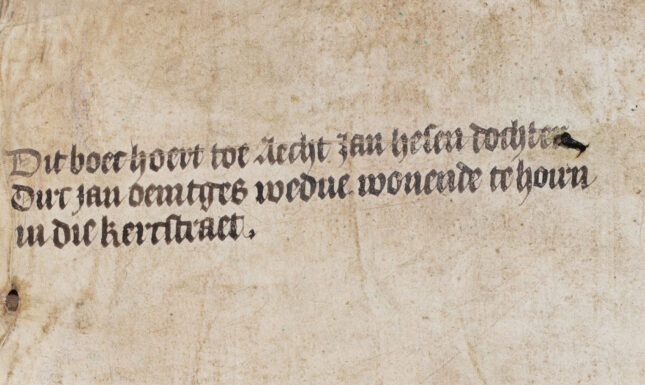

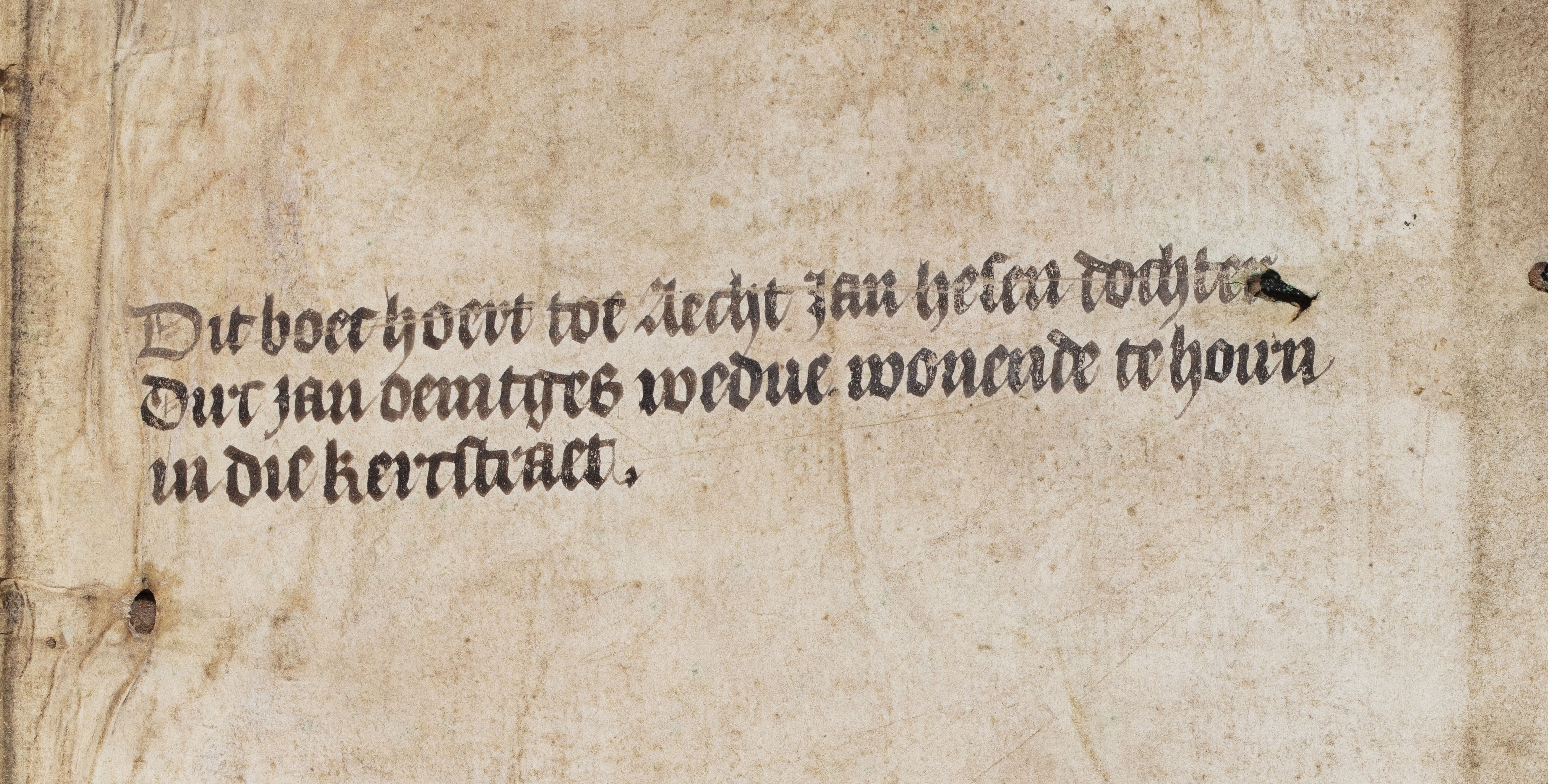

Jan Filipszoon’s prayer book, for example, does not only include a variety of texts that were brought together to suit his devotional needs. The manuscript is decorated with penwork in the so-called ‘loops style’, making it likely that the books was produced at the monastery of Lopsen or St Hieronymusdal in Leiden (As-Vijvers, ‘Manuscript production’, esp. p. 88). We also know that Jan Filipszoon bequeathed the book to his niece, Margriete Clasedochter. Similar data will also be included for copies of printed prayer books, such as the inclusion of manuscript leaves, decoration added by hand (Fig. 2) or owners’ marks (Fig. 4). Based on the explorative network analysis, sections of the prayer book-ecosystem will be selected for in-depth, qualitative analyses. These will focus on various aspects within the ecosystem: manuscripts, texts, and images. Long-term developments and the effects of the Medienwechsel will be analysed in the synthesis.

This way, the project hopes to grasp one of the most important books of the late medieval period in all its facets. Hopefully, the project will improve our understanding of the book’s (changing) function(s) within late medieval and early sixteenth-century religion and society and help uncover the practices, as well as more abstract notions and ideas, that underlie the manuscripts and printed books containing texts translated by Grote. Considering the variety of (combinations of) texts that we find in them, these ideas were undoubtedly much more diverse than the standard label, ‘Book of Hours’, would suggest.

You can follow the project's activities on our website and our Instagram. You can also browse the two manuscripts mentioned in this post in full: Deventer, Athenaeumbibliotheek, 101 E 24 KL and Leiden, UBL, BPL 2782.

Further Reading

Anne Margreet W. As-Vijvers, ‘Manuscript production in the monastery of St Hieronymusdal in Lopsen, near Leiden’, Oud Holland 134 (2021), 69-100.

Youri Desplenter, 'Het getijdengebed in het Nederlands', in: De Moderne Devotie. Spiritualiteit en cultuur vanaf de late Middeleeuwen, ed. by Anna Dlabačová and Rijcklof Hofman (Zwolle, 2018), 92-95.

Anne S. Korteweg, ‘Books of Hours from the Northern Netherlands Reconsidered: The Uses of Utrecht and Windesheim and Geert Grote’s Role as a Translator’, in: Books of Hours Reconsidered, ed. by Sandra Hindman and James H. Marrow (London and Turnhout, 2013), pp. 235-61.

The Golden Age of Dutch Manuscript Painting, ed. H.L.M. Defoer, A.S. Korteweg, and W.C.M Wüstefeld (Stuttgart, 1989).

R. Th. M. van Dijk, ‘Methodologische kanttekeningen bij het onderzoek van getijdenboeken’, in Boeken voor de eeuwigheid. Middelnederlands geestelijk proza, ed. Th. Mertens (Amsterdam, 1993), pp. 210-229 and pp. 434-437.

Frits van Oostrom, Wereld in Woorden. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse literatuur 1300-1400 (Amsterdam, 2013).

N. van Wijk, Het getijdenboek van Geert Grote; naar het Haagse handschrift 133 E21 (Leiden, 1940).

© Anna Dlabačová and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Anna Dlabačová and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.