Proverbial Pigs in the Middle Ages: Ten Medieval Proverbs Featuring Swine

Swine make a frequent appearance in the proverbs of the Middle Ages; this blog post provides a fair sample of medieval piggish wisdom!

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a proverb as “[a] short, traditional, and pithy saying; a concise sentence, typically metaphorical or alliterative in form, stating a general truth or piece of advice; an adage or maxim.” In other words, proverbs are nuggets of wisdom; together, they represent what is common knowledge in a given time and culture. Proverbs are usually phrased in familiar day-to-day terms and they are, therefore, often associated with ‘popular wisdom’; that is belonging more to the rustic old farmer in the field than the learned author writing in an elevated literary style. Given the importance of the pig in medieval culture (see my other contributions to the Leiden Medievalists Blog), it should come as no surprise that many proverbs feature references this animal. What follows in the remainder of this blog post is a selection of (at least) ten medieval porky proverbs.

1. The quiet sow eats the food of the grunting one

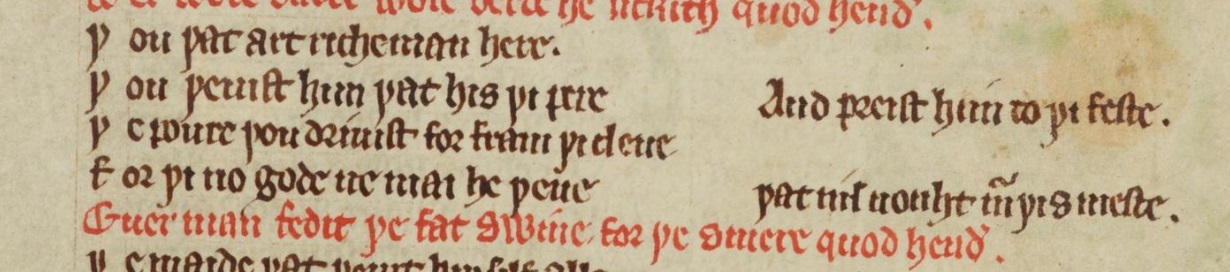

Above: Eating pigs (from London, British Library, Additional 18851, fol. 6r); Below: A Middle English proverb (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Rawlinson C. 641, fol. 13v).

Proverbs were page fillers. Parchment was expensive; so, when there was some empty space on a manuscript page left, scribes or later users would sometimes add little texts to fill out the page. Proverbs were highly suitable for this and the following piggy proverb was added to at least three late medieval English manuscripts:

“Si stille suge fret þere grunninde mete” [the quiet sow eats the food of the grunting one].

If you make too much noise, someone else will run away with whatever it is that you covet.

2. Old pigs have hard mouths

Proverbs are collectables: as representatitves of communal wisdom, proverbs were often gathered together in collections of sayings. Examples includes the biblical Book of Proverbs, the Old Norse Havamal and the late fifteenth-century Proverbia communia, a Middle Dutch proverb collection of more than 800 sayings. The Proverbia communia also includes various proverbs dealing with pigs:

- “Oude swinen hebben harde muylen” [old pigs have hard mouths]

- “Als tverken droomt so eest van draf” [if the pig dreams, it is of food]

- “Men en can gheen verken met semelen mesten” [one cannot fatten up a hog with bran]

[The standard edition of the Proverbia communia is Richard Jente (Ed.), Proverbia Communia – A Fifteenth Century Collection of Dutch Proverbs Together with the Low German Version, edited with commentary. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Publications, 1947]

3. He, who meddles among the bran, eats of the swine (or: is eaten by the swine)

Proverbs sometimes make an appearance in verbal duels, dialogues in which two speakers try to outdo each other by exhibiting their wisdom, often in the form of riddles and proverbs. One such verbal battle is the fifteenth-century Dialogue between Solomon and Marcolf. In one part of this text, the Old Testament King Solomon gives samples of ancient wisdom and the witty Marcolf responds with more rustic versions of his own. Some examples include:

- Solomon: Fede up youre children and from thayre youthe lerne thaym to do welle. [Raise your children and from their youth teach them to do well]

- Marcolf: He that fedyth well his cowe etyth often of the mylke. [He who feeds his cow well will often drink of the milk]

- Solomon: “He sekyth many occasions that wolle departe from his maister.” [He who wants to depart from his master seeks many opportunities]

- Marcolf: “A woman that wolle not consente seyth that she hath a skabbyd arse.” [A woman that does not want to consent says that she has a scabby arse]

Marcolf also has a proverb featuring swine up his sleeve:

“It is reson that he of the swyne ete that medlyth amonge the bren.” [It is logical that he, who meddles among the bran, eats of the swine.]

This proverb is rather enigmatic: perhaps the implied sense is that if you are in the right location you can benefit from this. The latest editors of the Dialogue between Solomon and Marcolf note that Marcolf here messes up a more common proverb, namely: He, who meddles among the bran, is eaten by the swine. That is: be careful with whom you keep company. A rustic alternative to Solomon’s “Wyth brawlyng people holde no companye” [do not keep company with contentious people].

4. One always feeds the fat swine for the lard

While most proverbs survive without any explanation, the late-thirteenth century collection of proverbs known as “The Proverbs of Hendyng” does introduce every proverb with an explicative note:

Cambridge, University Library, Ms. Gg.1.1, fol. 479r.

Þou þat art riche man here,

Þou ȝevist him þat his þi pere,

And preist him to þi feste;

Þe povre þou drivist for fram þi cleve,

Forþi no gode ne mai he ȝeve,

Þat nis nouht in þis meste.

'Ever man fedit þe fat swine for þe smere'

[You who are a rich man here,

You give to him who is your equal

And invite him to your feast

The poor person you drive far from your dwelling

Because no good can he give,

who is not the most in anything.

'One always feeds the fat swine for the lard']

In other words, people will only help those from whom they can profit themselves.

5. ‘Now it is in the judgement of the pig’, said the man who sat on the boar’s back

“Nu hit ys on swines dome”, cwæð se ceorl sæt on eoferes hricge.”

This rather puzzling proverb is part of the so-called Durham Proverbs, an 11th-century collection of 46 proverbial statements in Latin and Old English. Its form, consisting of a statement, a speaker and an often humorous context, is known as a Wellerism (named after a character from Charles Dickens, see this Wikipedia article). The meaning of this Durham proverb seems to be that there are moments when things are out of your control, especially if you decide to hitch a ride on a boar (for this medieval motif, see my earlier blog post: Medieval piggyback rides: Riding boars in the Middle Ages).

6. After the boar the doctor and after the deer the stretcher

Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Bodl. 546, fols. 3v, 17r

Hunting was a dangerous sport in the Middle Ages, since some animals would put up a fight. The boar, in particular, was notorious for attacking and wounding its pursuers. But according to Edward of Norwich, author of the Master of Game (1406-1413), there was one animal even more dangerous than the boar: the deer. Edward insists that an attack by a deer will cause incredible pain and struck hunters are unlikely to recover: “And þerfore men seyen yn old sawes. After þe boor þe leche and after þe hert þe bere” [and therefore people say in old teachings: After the boar the doctor and after the hart the stretcher].

7. When swine are cunning in all points of music and pigs are made poets for their eloquence

When we want to say that something is unlikely to happen, we can use the phrase “When pigs fly”. The fifteenth-century song When Nettuls In Wynter Bryng Forth Rosys Red [When nettles in the winter bring forth red roses] uses a whole list of similar, unlikely scenarios, including ‘when mice move mountains by wagging their tails’; ‘when asses are doctors of every science’; and ‘when herrings blow their horns in the forest’. This litany of unlikely scenarios also includes references to pigs (and a rather misogynist refrain):

“Whan swyn be conyng in al poyntes of musyke.

…

And pygs be mad poets for their eloquens;

Than put women in trust and confydens.

[When swine are cunning in all points of music

...

and pigs are made poets because fo their eloquence

Then put in women trust and confidence.]

You can read the full version of this song here.

8. A fair woman who is not chaste, is like golden ring through a sow’s nose

Medieval proverbs often have misogynist overtones. Some examples of this are found in the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer (1343-1400). In his Nun’s Priest Tale, for instance, we are told: “Wommennes conseils been ful ofte colde” [A woman’s counsel is very often fatal] (NPT, l. 3256). In The Wife of Bath’s Tale, Chaucer applied another anti-feminist proverb:

`A fair womman, but she be chaast also,

Is lyk a gold ryng in a sowes nose.' (WoBT, ll. 784-785)

[A beautiful woman who is not also chaste, is like a golden ring through a sow’s nose]

9. Whoever wants to live with swine, will learn how to grunt.

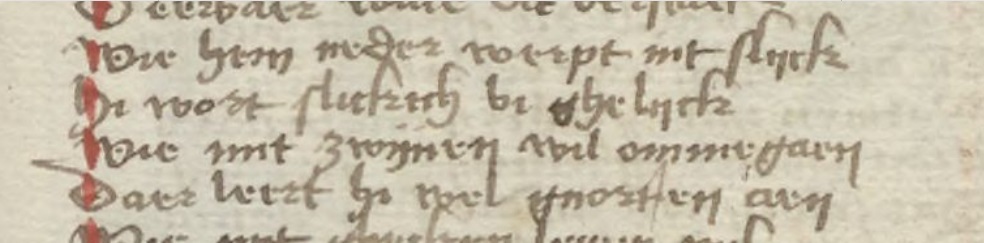

While proverbs are often associated with rustic, popular wisdom, some proverbs also make their appearance in more profound literature. A case in point is the following proverb in Der Minnen Loep [The Mirror of Love], a long didactic poem about love by Dutch writer Dirc Potter (c. 1370-1428); the proverb is found in a section in which Potter warns noble ladies about the company they keep:

Leiden, University Library, LTK 205, fol. 17r.

Wye him neder werpt inden slijck,

Hi wart vul slikich bij ghelijck.

Wye mit zwinen wil omme gaen,

Daer leert hi wael gnorren aen.

[Whoever throws themselves down in the dirt,

they will equally become dirty.

Whoever wants to live with swine,

will learn how to grunt.]

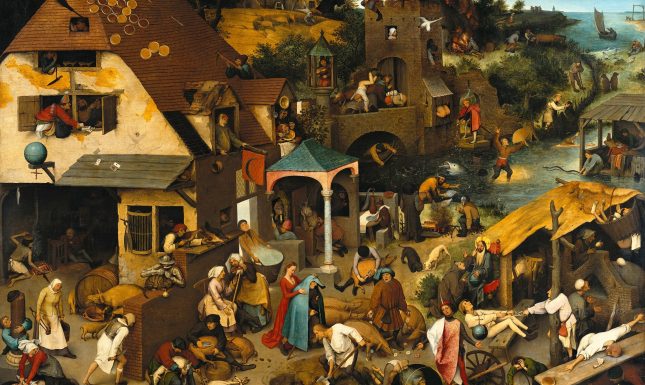

10. Pig proverbs in Pieter Brueghel’s Netherlandish Proverbs (1559)

As we have seen, pigs played an important role in the medieval proverb tradition. This is confirmed by the 16th-century painting Netherlandish Proverbs (1559) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder; building on the medieval proverb tradition, Bruegel included no fewer than six proverbs having to do with pigs:

- The pig is stabbed through the belly [A foregone conclusion or what is done can not be undone]

- One shears sheep, the other shears pigs [One has all the advantages, the other none]

- When the gate is open the pigs will run into the corn [Disaster ensues from carelessness]

- When the corn decreases the pig increases [If one person gains then another must lose]

- The sow pulls the bung [Negligence will be rewarded with disaster]

- To cast roses before swine [To waste effort on the unworthy]

I am sure this last proverb does not apply to this blog post!

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.