“Of those things that prohibit the conception”. Birth control in Renaissance Italy

What contraceptive methods did people in Renaissance Italy use? And how was knowledge about these techniques transmitted? Find out in this blog!

Available methods

Nowadays, men and women who want to have sex and avoid a pregnancy can choose from a wide array of products, including condoms, pessaries, and hormonal contraception. Women who are already pregnant can choose to terminate their pregnancy by use of medication or surgery. These possibilities not only protect women from pregnancies that could harm their health, but also enable single women and couples to plan their lives in a way that best suits their interests and those of their (prospective) family.

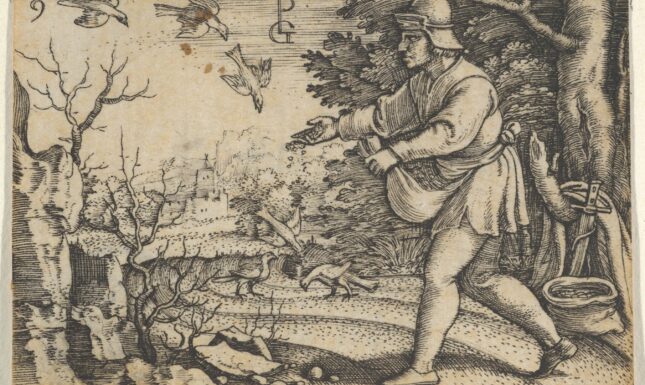

In Renaissance Italy, methods of birth control were not nearly as reliable as those of modern societies, but people still tried to take control over their sex lives by those methods that were available. The earliest description of condom use derives from the second half of the sixteenth century: in De Morbo Gallica (pub. 1563), physician Gabriele Falloppio recommends the use of linen sheaths over the glans of the penis as a protection against syphilis. Using condoms for birth control, however, only became more common during the seventeenth century. Coitus interruptus was a much more widely practiced technique. In manuals for confession, aimed at guiding a member of the clergy in taking confessions, it is described in technical terms as “redrawing oneself before completion of the act and emitting semen outside of the proper vase”. In a moralistic treatise aimed at newlyweds, preacher Cherubino da Spoleto compares it in more poetic terms to “working in a field, but then sowing the seed on the rocks” – perhaps referring to the Parable of the Sower (Matthew 13:1-9,18-23).

Apart from condoms and coitus interruptus, most methods of birth control were aimed at the female rather than the male partner – as is still the case with modern medicine. Literary works already provide a glimpse of the techniques that were available for women. Bartolomeo Gottifredi’s Specchio d’Amore for instance mentions “waters, stoves, baths and syrups” [acque, stuffe, bagni o siroppi] that prevent women from getting pregnant or make them miscarry, while Masuccio Salernitano’s Novellino mentions the use of “poisonous drinks both below and above [de sotto e de sopra]”.

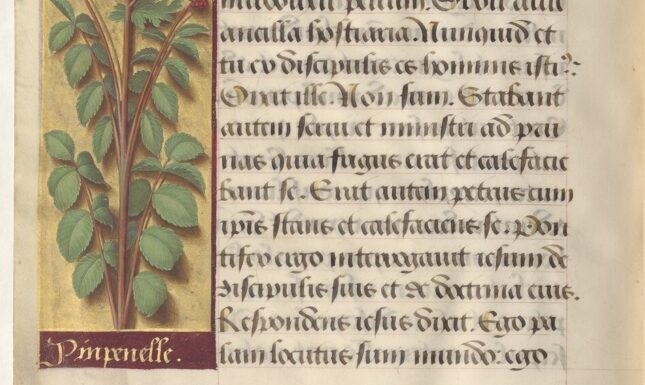

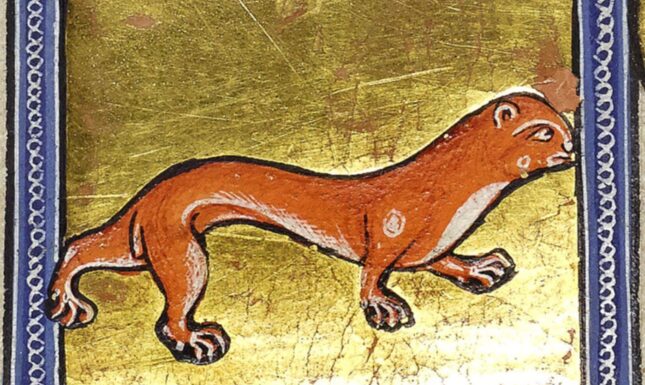

More specific information comes from works of medicine. Pietro Bairo’s Secreti Medicinali includes a small chapter with the explicit title “Of those things that prohibit the conception”, including numerous remedies. (I do not recommend trying any of these at home!) Some of these remedies need to be applied locally after coitus, such as putting saltpeter or alum, “about as much as a bean”, inside the vagina or “using pepper assiduously”. Others are herbal medicines to be taken orally, such as the roots of the pimpinella, and the tops and grains of the hellebore. Many methods have a more magical character. Wearing a talisman made from the testicles of a male weasel, the heart bone of a deer, or even iron filings, in a little sachet between the breasts is supposed to impede pregnancy, as well as wearing a ring made of agate or emerald.

Contraceptive methods are not often explicitly mentioned in works of medicine. However, according to historian John Riddle, many medical treatises did include hidden information on how to cause an early-term abortion. Chapters on how to provoke retained menstruation, expel the afterbirth, induce menstruation postpartum, or expel a dead fetus all include herbal remedies that were not officially meant to be used as abortifacients, but could nonetheless have the same effect. Both Pietro Bairo’s Secreti Medicinali, and a treatise on conception by Michele Savonarola include chapters of this nature, listing drinks and pessaries made from herbal ingredients that could procure an abortion. Often mentioned ingredients are black hellebore and pepper – which Bairo later also mentions as contraceptives. Other ingredients include myrrh, juniper, chamomile and peony, which from classical antiquity until the nineteenth century were known as abortifacients as well.

From left to right: Image of a pimpinella from the Horae ad usum Romanum, c. 1503-1508 (BnF Gallica). Gold and emerald ring, found in Buckinghamshire, c. 1200-1450 (Colchester Ipswich Museum Service). Image of a weasel from the Aberdeen Bestiary, c. 1200 (Aberdeen University Library, Univ. Lib. MS 24, folio 23v).Transfer of knowledge

It is possible that some people first came across these methods of birth control through the written word. The character Arsiccio in Antonio Vignali’s work of satire La Cazzaria claims that scholars are the best possible lovers because of all the knowledge and skills that they have picked up during their studies. These scholars not only know “all the secret ways of pleasure”, but also know “many secrets that allow them to have sex with housemaids and widows without getting them pregnant, and when they become pregnant, to make them miscarry”.

But scholars reading Latin were of course not alone in their access to knowledge of birth control. The books of medicine by Bairo and Savonarola were written in the vernacular and aimed at a public that was much broader than students or medical professionals. Moreover, it is likely that much knowledge about birth control was transferred orally as well. Literary works written by male authors sometimes describe an exchange of this knowledge among women. In Bartolomeo Gottifredi’s Specchio d’Amore, an older woman called Coppina gives a younger, inexperienced woman called Maddalena advice on how to have a secret love affair. She states that many women have learned how to “govern a love” by reading books “of amorous histories”. These women “know many secrets and know how to do many things that all should be hold dear by a girl in love: how to make waters, stoves, baths and syrups so that you don’t become pregnant, or, when you are pregnant, how to abort it”. Coppina offers to share her own knowledge of these things with Maddalena, if she is ever in need of it, as “it has showed me how to do mine” [e.g. her own abortion, questo mi mostrò a fare il mio].

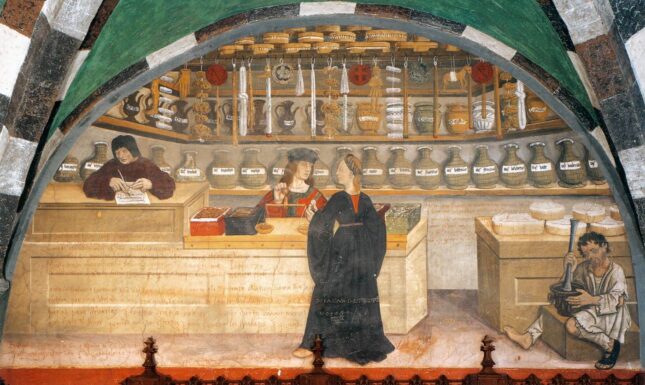

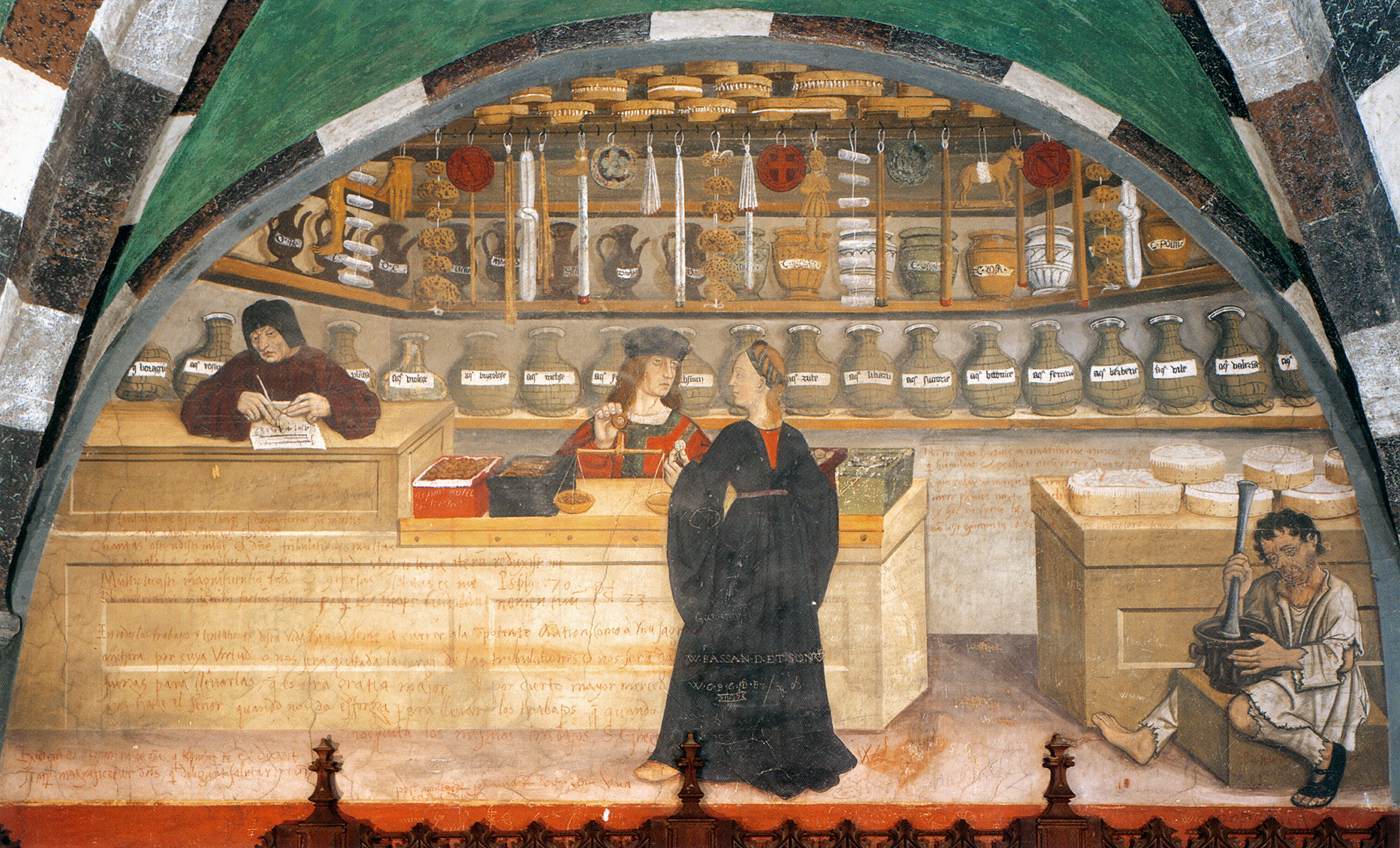

The ingredients needed to prepare those “waters, stoves, baths and syrups” of course had to come from somewhere. While lay people may have been able to acquire some of these ingredients themselves or through informal channels, professional physicians and apothecaries played a role in this as well. That the church was worried about the potential involvement of these professions in birth control practices, is clear from manuals of confession. The manuals of Bartolomeo Caimi and Pacifico da Cerano include lists of specific questions to guide the confession of medical professionals in particular. While taking the confession of a physician or surgeon, the confessor should ask whether they had given council or medicine of a type “that helped the body but endangered the soul”. This included “giving medicine to a pregnant woman so that she would miscarry, or kill the creature that she has inside her body to preserve her honor or her life”. Apothecaries had to be asked whether they, knowingly, had sold others the poisons [venena] to procure an abortion.

Degree of acceptance

Clerical authors mention several motives to avoid having offspring, often separating the motives of men and women for doing so. In his treatise on marriage for newlyweds, preacher Cherubino da Spoleto first addresses the men in his audience, accusing them of “lacking spirit” and “being cowards [pusillanimi]” because they don’t want to take care of any more children and therefore “sow their seed on the rocks”. After that, he directs his attention to the women, stating that women “take up ways not to get pregnant, or if they are pregnant, to force themselves to miscarry” simply because they want to be free to do as they please [per potere esser libere d’andare a lor modo di qua e di là]. Pacifico da Cerano likewise mentions family planning (“not being able to nourish any more children”), as well as some motives that apply to women in particular: from “preserving her life”, when a woman’s health is in danger, to “preserving her honor”, when a woman wants to hide her fornication or adultery, and wanting “to stay beautiful”.

The majority of the clergy considered all of these motives unlawful: using birth control for these reasons was a mortal sin that required confession and repentance if one wanted to avoid eternal damnation. But there were exceptions to the rule as well. Angelo da Chivasso, the author of one of the most authoritative manuals for confession in Renaissance Italy, accepted family planning as a legitimate excuse. He took a more lenient stance on coitus interruptus, stating that if a man withdraws, or if a woman stands up or urinates directly after sex to emit the semen, this is not a mortal sin if the goal is to limit their offspring because they cannot take care of them.

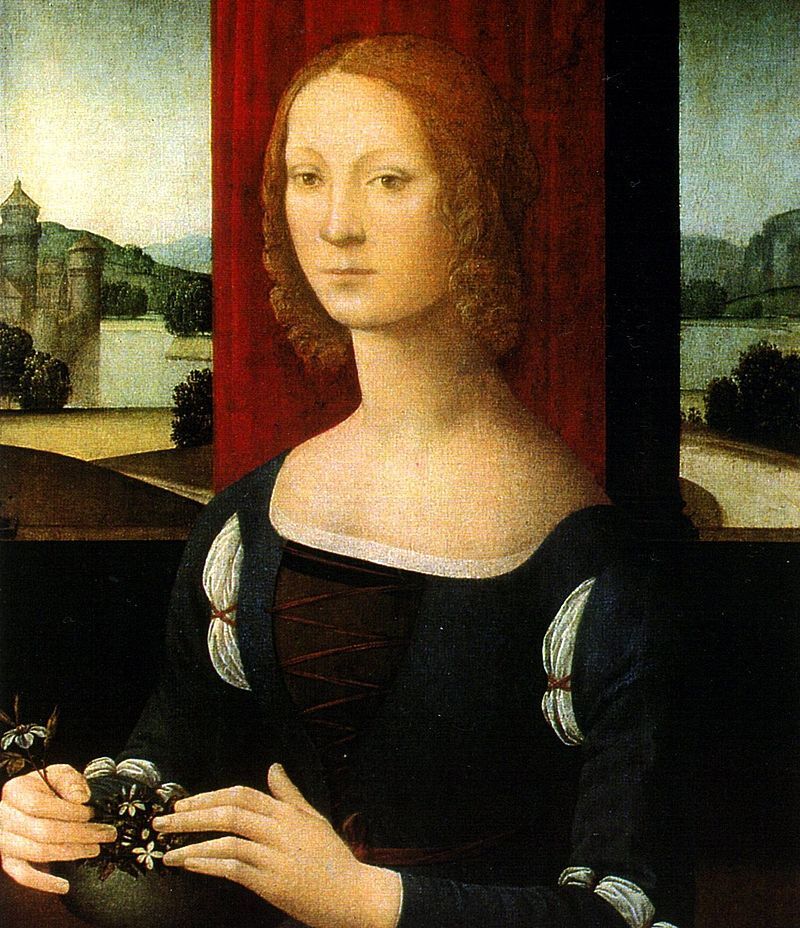

It is also important to note that clerical opinions about the degree of sin could vary in accordance with the duration of the pregnancy and the sex of the child. One of the most important medieval authorities on this topic was Church Father Augustine. Basing himself on Aristotle, he stated that the soul does not enter the fetus until the fortieth day after conception, and the laws of homicide therefore do not apply to those who remove a fetus before that day. This view was held by influential theologians like Albert Magnus, Thomas Aquinas and Giles of Rome. A fifteenth-century Italian representation can be found in the manual of Pacifico da Cerano. He writes that it should only be considered murder and a mortal sin “if a pregnant woman voluntarily causes herself to miscarry and if this happened for a male child forty days after the conception, and for a female child thirty days, because according to Saint Augustine this is the time it takes for bodies to take complete form as well as a soul”. These ideas reached a broader lay audience as well – it is for instance mentioned in a collection of medical recipes written by noblewoman Caterina Sforza called Experimenti. This collection includes a “marvelous experiment to bring on a miscarriage before the fortieth day”.

Medics, who valued the health and wellbeing of their patients, were less strict on the topic of contraceptive and abortive medicine. Pietro Bairo violated the Church’s prohibitions by providing contraceptive and abortive remedies in his Secreti Medicinali. Perhaps to avoid censorship on moral grounds, he did warn physicians to only use these for “a legitimate cause”. These causes included the preservation of the life of the woman, as well as family planning. One of his recipes is recommended for “a woman who has given birth and for some good cause [per qualche buona causa] does not want to get pregnant for some time”.

Primary sources:

Pietro Bairo, Secreti Medicinali

Bartolomeo Caimi, Interrogatorium

Pacifico da Cerano, Summa Pacifica

Angelo da Chivasso, Summa Angelica

Bartolomeo Gottifredi, Specchio d’amore

Michele Savonarola, Ad mulieres ferrarienses

Cherubino da Spoleto, Regola della vita matrimoniale

Antonio Vignali, La cazzaria

Further reading:

For the scholarly debate on recipes for provoking menstruation/afterbirth as hidden abortifacients, see: J.M. Riddle, Eve’s Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West (Cambridge, MA 1997) and J. Cadden, ‘Western Medicine and Natural Philosophy’ in: V.L. Bullough and J.A. Brundage eds., Handbook of Medieval Sexuality (New York/London 1996).

For theological perspectives on contraception, see: J.T. Jr. Noonan, Contraception: A History of Its Treatment by the Catholic Theologians and Canonists (Cambridge, MA 1986).

For Caterina Sforza’s Experimenti, see: M.K., Ray, ‘Impotence and Corruption: Sexual Function and Dysfunction in the Early Modern Italian Books of Secrets’ in: S.F. Matthews-Grieco ed., Cuckoldry, Impotency and Adultery in Europe (15th-17th century) (Farnham/Burlington 2014).

© Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.