“My object is truth”: An Old English Homilist and Religious Polemics in Nineteenth-Century Britain

In today's society, public discourse often loses sight of the commonsensical ‘middle of the road’. The nineteenth century was not much different. Only, back then, Europe's great minds were drawn into debating the intricacies of early medieval Christian doctrine, rather than the mysteries of Crypto.

The nineteenth century is often seen as a time in which the gaze of public figures and intellectuals was redirected towards the mists of history, in an attempt to make sense of the present and the contingencies of the future. Rocked to its foundations by waves of revolutionary fervour, the European zeitgeist underwent a 'historical turn', a 'search for origins', in the hopes of restoring sure footing on a strong historical base. One of the arenas where this search for origins was played out was the emerging field of comparative-historical philology. Another was a school of ecclesiastical history newly critical of its fundamental sources. In fact, both arenas tended to overlap, especially in the first half of the nineteenth century. In this blog post, I highlight this intensified historical awareness by focusing on a debate surrounding the doctrinal position of an Anglo-Saxon abbot, Ælfric of Eynsham (955–1010), between two key players from nineteenth-century Britain: John Lingard (1771–1851; Catholic priest and historian) and Henry Soames (1785–1860; Anglican clergyman and church historian).

An objective science, or a vehicle for ulterior motives?

As language scholars and historians began feverishly scrounging the past in search of the ur-language, the ur-nation, the ur-spirit and other things alluringly ur- at the turn of the nineteenth century, a course was set in the direction of a systematic and critical treatment of history, coupled with a trend of increasing professionalization and specialization at the new ‘research university’, which blossomed in late nineteenth century (Turner, 233-234). But this process of professionalization was a long one, and, arguably, one that remains yet unfinished. Hidden agendas and ideological frameworks continued to steer and influence scholars far past the mid-point of the nineteenth century. Even a figurehead like J.M. Kemble, an early promoter in Britain of the new comparative-historical method of philology developed by the likes of Jacob Grimm and Rasmus Rask, was hampered, as Allen Frantzen put it, by “an attitude toward the past” which recognized in the latter “a vital relationship to the present” (58). This meant that when historians and language scholars of a like mind to Kemble directed their attention to, for example, Anglo-Saxon history, “they saw there the beginnings of traditions which they themselves wished to claim” (58). For much of the nineteenth century, philologists stood “with one leg in the field of literature and learning, with another in the arena of politics and its emerging institutions” (Leerssen 2018: 195). Strong ulterior motives lurked behind ostensibly ‘scientific’ scholarship.

In the field of ecclesiastical history, too, new historical-critical methods did not immediately replace traditional models of making sense of human time and development; they intermingled. This intermingling happened against a backdrop of unprecedented growth in Victorian Britain, and western Europe more generally. Western industrial capital and imperial might spread across the globe. One of the ways to make sense of this miraculous progress was to marry the old idea of a universal history, helmed by God, to new-fangled perspectives on the history of Christianity (Bennett 2019: 4-5). Mainstream Protestants in Britain, especially, began “to locate present and future progress within a spiritual framework stretching across time” (Bennett 2019: 6). This naturally led to a reappraisal of church history among Protestants. What about those thousand years separating the fall of the Roman Empire and the Reformation? Perhaps they were not all full of popish superstition and suppression. Perhaps that era of darkness served some good after all. Perhaps it paved the way for the Protestantism that they now enjoy. Contemporary polemics and a heightened historical consciousness became allies in a nineteenth-century endeavour to clarify the direction of human progress.

Lingard, Ælfric and the fight over Anglo-Saxon England

Someone who worked during this uneasy alliance between recent methodological advances and lingering religious polemics was the Catholic historian and priest, John Lingard. Writing in a comparatively early phase, when the wind of historical criticism had only recently arrived on British shores, Lingard purposively positioned his research in opposition to the biased and skewed historiography of the past, which had been soiled by a religious controversy that “pervaded every department of literature” (Lingard 1806: iii). Explicitly distancing himself from his predecessors, Lingard proclaimed his sole object to be “truth,” and he considered it his “religious duty to consult the original historians” (Lingard 1806: iv). He even felt confident enough – following the Catholic Relief Act of 1791, and with voices being raised in favour of Catholic Emancipation (passed in 1829; Figure 1) – to redress, in his view, a thorny issue that had plagued English history writing ever since the Reformation: Was the church of early medieval England fully entrenched in the Roman-Catholic fold, or did it go about doing its own thing (that is, ‘proto-Protestant’)? The latter had been enthusiastically argued by Protestants from archbishop Matthew Parker (1504–1575) onwards (Magennis 2015: 243). One of the Old English texts that had seemed to present incontrovertible proof of Protestantism’s ancient roots in England was a homily by Ælfric dealing with the nature of the transformation of the eucharistic elements during Communion (Figure 2). A passage often cited by Protestant reformers was the following:

Micel is betwux þære ungesewenlican mihte þæs halgan husles. and þam gesewenlican hiwe agenes gecyndes; Hit is on gecynde brosniendlic hlaf. and brosniendlic win. and is æfter mihte godcundes wordes. soðlice cristes lichama and his blód. na swa ðeah lichamlice. ac gastlice; (“Sermo de sacrificio in die Pascae,” ll. 124–128)

[Much is between the invisible power of the blessed Eucharist and the visible form of its actual origin; it is originally perishable bread and perishable wine, and is, after the power of the divine word, truly Christ’s body and his blood, but in a spiritual way, not bodily].

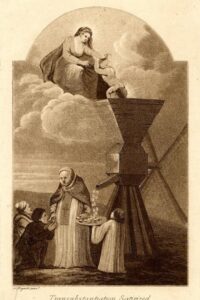

Spiritually, not bodily—there’s almost nothing more pleasing to the ear of a Protestant having only recently thrown off the popish yoke, than a phrase that appears to reject the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation (the bread and wine are substantially transformed into the body and blood of Christ; see Figure 3). But to Lingard, a staunch Catholic, this was unacceptable, of course.

In an extensive note on ‘Belief respecting the eucharist’ at the end of the first volume of his Antiquities of the Anglo-Saxon Church (1806), we can see Lingard fall somewhat short of his noble intentions set out before in his preface. In it, he gives a rather sarcastic description of the surprise that some (Protestant) readers might feel upon learning that he has “dared to pronounce the doctrine of the real presence, to have been the doctrine of the Anglo-Saxon church” (359):

What! he will ask, have not Parker, and Lisle, and Usher, and Whelock, and Hicks, and Collier, and Carte, and Littleton, and Henry, shewn that the ancient belief of our ancestors, respecting the sacrament of the eucharist, perfectly coincides with that established by the reformed churches? (359)

Just in case this statement was not convincing enough, he moves on to discredit Ælfric and his Paschal Homily, a text which has caused so much undue confusion over the centuries. He relegates the time of the homilist to a period that “may almost be called an age of darkness” and Ælfric himself to a member of a lacklustre group “fewer in number, and inferior in merit,” compared to previous ages (342). According to Lingard, Ælfric was merely following in the footsteps of a continental theologian, Ratramnus, who like other “ingenious men” had fallen a bit too deep into “the privilege of speculating on the mysteries of Christianity” (353). As a result, Ælfric’s “language and distinctions were certainly singular” and, hence, quite outside mainstream Anglo-Saxon orthodoxy: “With respect to them Ælfric stands alone” (354). All the same, Lingard insists that both Ælfric, as well as his continental guide, expressed opinions “not repugnant to the established doctrine of the catholic church” (353–354). They just let their intellectual speculations run too wildly, which left them open to attack later on from Protestant revisionists.

Some back-and-forths with Soames

This return to form of the Catholic side could not, of course, pass without comment from the opposition. In 1830, Henry Soames published a lecture series under the title An Inquiry into the Doctrines of the Anglo-Saxon Church, reinforcing once again the Anglican position in the debate. Soames, in contrast to Lingard, creates a decidedly more positive characterization of Ælfric:

…that master-spirit of his age the zealous and laborious Ælfric, a writer not by any means outdone, in controverting Romish eucharistic doctrines, even by the homilists, and other theologians who have appeared in England, since the Reformation. (384)

Nor does Soames hold back from reclaiming Ælfric as a proto-Protestant flagbearer and an exemplary ambassador of Anglo-Saxon church’s official stance in subsequent publications. In The Anglo-Saxon Church (1835), for instance, he asserts that Ælfric’s writings prove “forcibly and clearly, that the ancient Church of England never wavered in her invaluable testimony against transubstantiation” (242). Lingard, in response to these jabs by Soames, adds a new ‘note’ to the revised 1845 edition of his Antiquities (now called History and Antiquities), in which he restates his claim that Ælfric held only a minority position within the Anglo-Saxon church, derived mostly, at that, from speculative theologians on the continent. He also addresses the fact that there was a whole host of early medieval authors and clergymen who presented more strictly orthodox views: “Why is their authority to be set aside, and no attention to be paid to any one but to Ælfric? Is it not because he has adopted a sort of language very different from theirs?” (459). Protestants were cherry-picking their way through history.

Not so, according to Soames in his Latin Church during Anglo-Saxon Times

(1848). True, Ælfric relied heavily on the work of Ratramnus, a “foreign author, but then, he apparently never felt the need to provide an explanation for skirting the edge of orthodoxy like this, proving that “Ratramn[us] wrote very much as Englishmen generally thought” (424). Soames thought, perhaps, that whereas Lingard ostensibly restricted himself to the ‘history’ and ‘antiquities’ of the Anglo-Saxon church, he himself, along with his compatriots, continued to “take their stand” firmly on its ‘doctrine’ – doctrine which, in their view, was very much in line with modern Protestantism (425).

Conclusion

Now, it would seem that Soames got to have the last laugh in this entire affair. Lingard died in 1851, but his rival went on to live nine more years. Plenty of time to settle the matter in favour of the Protestant camp once and for all. Curiously, though, the fourth and final edition of Soames’ Anglo-Saxon Church, published in 1856, turned out much less polemical than its previous editions had been. As Soames himself says in a newly-added advertisement: “Nor have notes, directly controversial, been retained. They gave to former editions a character somewhat polemical, but adverse opinions have not been so well established as to render the continuance of these notes any longer necessary” (17–18). This may have been a mercy killing dealt out by Soames to Lingard’s ‘adverse opinions’. But, perhaps, this comment by Soames also reflects a change in the academic modus operandi. Overt religious polemics were going out of fashion at this point in favour of more ‘objective’ (whether feigned or unfeigned) research.

Bibliography

- Ælfric of Eynsham. “Sermo de sacrificio in die Pascae.” In Ælfric’s Catholic Homilies: The Second Series, edited by Malcolm Godden, 150-160. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979.

- Bennett, Joshua. God and Progress: Religion and History in British Intellectual Culture, 1845 – 1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Leerssen, Joep. National Thought in Europe: A Cultural History. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2018.

- Lingard, John. The Antiquities of the Anglo-Saxon Church. Vol. I. Newcastle: Edward Walker, 1806.

- Lingard, John. The History and Antiquities of the Anglo-Saxon Church. Vol. II. London: C. Dolman, 1845

- Magennis, Hugh. “Not Angles but Anglicans? Reformation and Post-Reformation Perspectives on the Anglo-Saxon Church, Part 1: Bede, Ælfric and the Anglo-Saxon Church in Early Modern England.” English Studies 96, no. 3 (2015): 243-263. (See also part 2 of this article for the nineteenth century)

- Soames, Henry. An Inquiry into the Doctrines of the Anglo-Saxon Church. Oxford: Samuel Collingwood, 1830.

- Soames, Henry. The Anglo-Saxon Church: Its History, Revenues, and General Character. London: John W. Parker, 1835 (4th ed.: 1856).

- Soames, Henry. The Latin Church During Anglo-Saxon Times. London: Longman, Brown, Green, & Longmans, 1848.

This blog post is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program (EMERGENCE, Grant agreement No.101115867, https://doi.org/10.3030/101115867 ). Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

© Lucas Gahrmann and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Lucas Gahrmann and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.