Multilingualism in Anglo-Saxon England: The art of glossing and translating

We are hardly shocked when visiting different countries and cities to hear a variety of languages. However, the reality of multilingual spaces and societies predates our modern times, as a study of the Anglo-Saxon period shows.

Multilingualism is a modern twentieth-century construct which revolves around the notion of proficiency in several languages. However, it is known that ancient cultures such as the Greeks, Romans, Ottomans and Anglo-Saxons were able to communicate in a variety of languages, and the version of multilingualism that emerges from these cultures is a much more fluid one.

The British Isles, originally Brittonic-speaking, owe their multilingual past mainly to the four major continental invasions: the Romans (1st century), the Germanic tribes (5th century), the Norsemen (8th century) and the Normans (11th century), speakers of Latin, Germanic, Old Norse and Old French, respectively. While these are the main four languages which interacted during the Middle Ages with Old and Middle English (the medieval varieties of English written and spoken during the time) more recent scholarship has shifted its focus to often overlooked languages such as Greek, Welsh, Dutch and Norn – the latter a later form of Old Norse spoken in the Northern Isles of Scotland.

Runes and multilingualism

Such a mixture of cultures and languages attests to the fact that Anglo-Saxon Britain was a multicultural and multilingual place, a reality palpable through the material artifacts that have come down to us from this period.

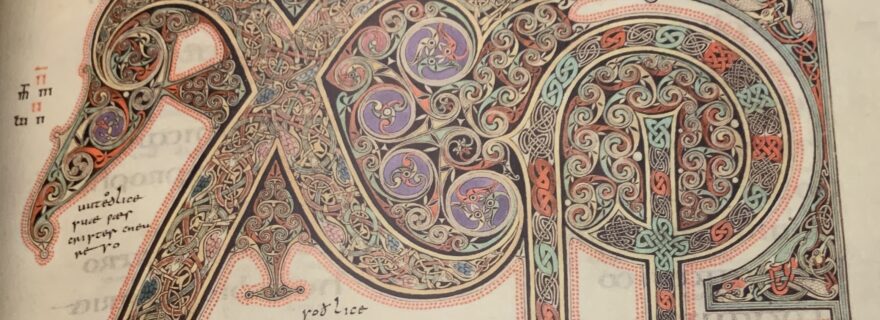

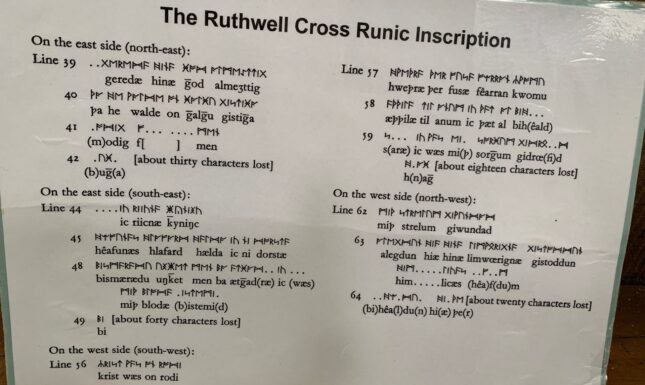

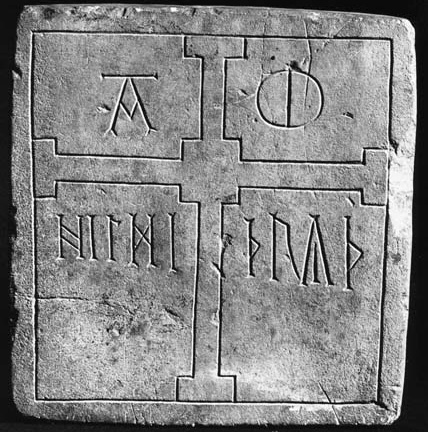

Consider the images in the carousel above, which show runic inscriptions on the 8th-century Ruthwell Cross in Scotland, or the image below (click on the arrows in upper-right corner to view in full) showing the 8th-century grave marker dedicated to Saint Hilda of Whitby. There are many cool aspects about these two objects, but given the scope of this blog post, I will focus on the linguistic aspect only.

First of all, you will notice that both artifacts present inscriptions written in runic characters, that is, the Germanic writing system which was used before the adoption of the Latin alphabet following the Christianisation of the British Isles. The runic inscriptions found on the sides of the Ruthwell Cross (images 1 and 2 of carousel), present part of a longer Anglo-Saxon poem known as The Dream of the Rood where Christ’s cross (or rood) gives its own detailed account of the crucifixion (image 2). Equally interesting is the inscription on the grave marker (see bottom half of image), which can be transcribed as follows: hildi / þryþ, giving the name of Saint Hilda to whom the grave marker was dedicated. Interestingly, on the upper half of the marker, you can see the Greek Alpha and Omega symbols, references to God. These wonderful objects demonstrate the mixture of languages, scripts and cultures in Anglo-Saxon England: Greek alongside runic symbols; runic inscriptions retelling part of The Dream of the Rood which is later found written down in the 10th-century Vercelli Book using the Latin alphabet; runic (that is, Germanic) symbols carved on clearly Christian artifacts.

Glosses and translations as evidence of multilingualism

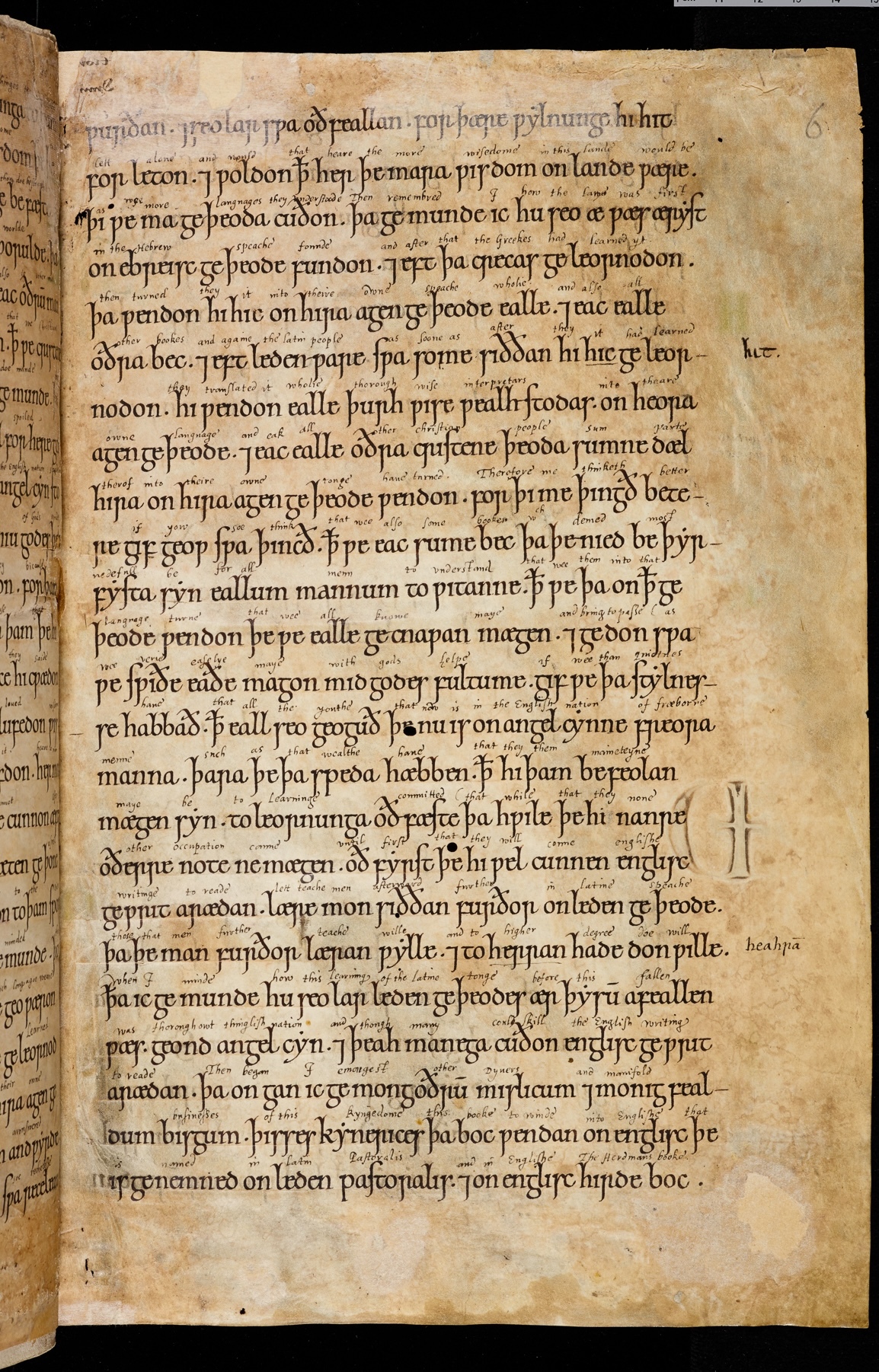

Another very valuable source of language mixing and its multilingual outcomes are glosses and translations. In the context of Anglo-Saxon literature, it is mainly texts originally written in Latin that were given Old English translations and glosses, many of which are of a religious nature (for an exciting and recent new find in Alkmaar, Netherlands, see here). In this regard, it is a must to mention King Alfred the Great (849-899) who, outraged by the lack of command and understanding of Latin by his fellow Anglo-Saxons, set out an impressive educational campaign aimed at improving literacy. He did so by ordering the translation of key religious Latin texts into Old English. Although it is disputed whether King Alfred translated any of these texts himself, we do hear from him, for instance, in the preface to the Old English translation of Pope Gregory the Great’s Cura Pastoralis (or Pastoral Care). Here, we soon discover the driving force behind his educational reform:

“Ðæt we eac suma bec, ða ðe niedbeðearfosta sien eallum monnum to wiotonne, ðæt we ða on ðæt geðiode wenden ðe we ealle gecnawan mægan (...) ðætte eall sio gioguð ðe nu is on Angelcynne friora monna, ðara ðe ða speda hæbben ðæt hie ðæm befeolan mægen, sien to leornunga oðfæste, ða hwile ðe hie to nanre oðerre note ne mægen, oð ðone first ðe hie wel cunnen Englisc gewrit arædan”

[that we too translate them, some of those books which all men most need to know, that we too translate them into the language that we can all perceive (...) that all the youth which is now in England of the free men who have the means to apply themselves to this be set to learning while they can be used for no other purpose, until such time as they well know how to read what is written in English – translation from North, Allard, & Gillies (2011: 434) – my emphasis].

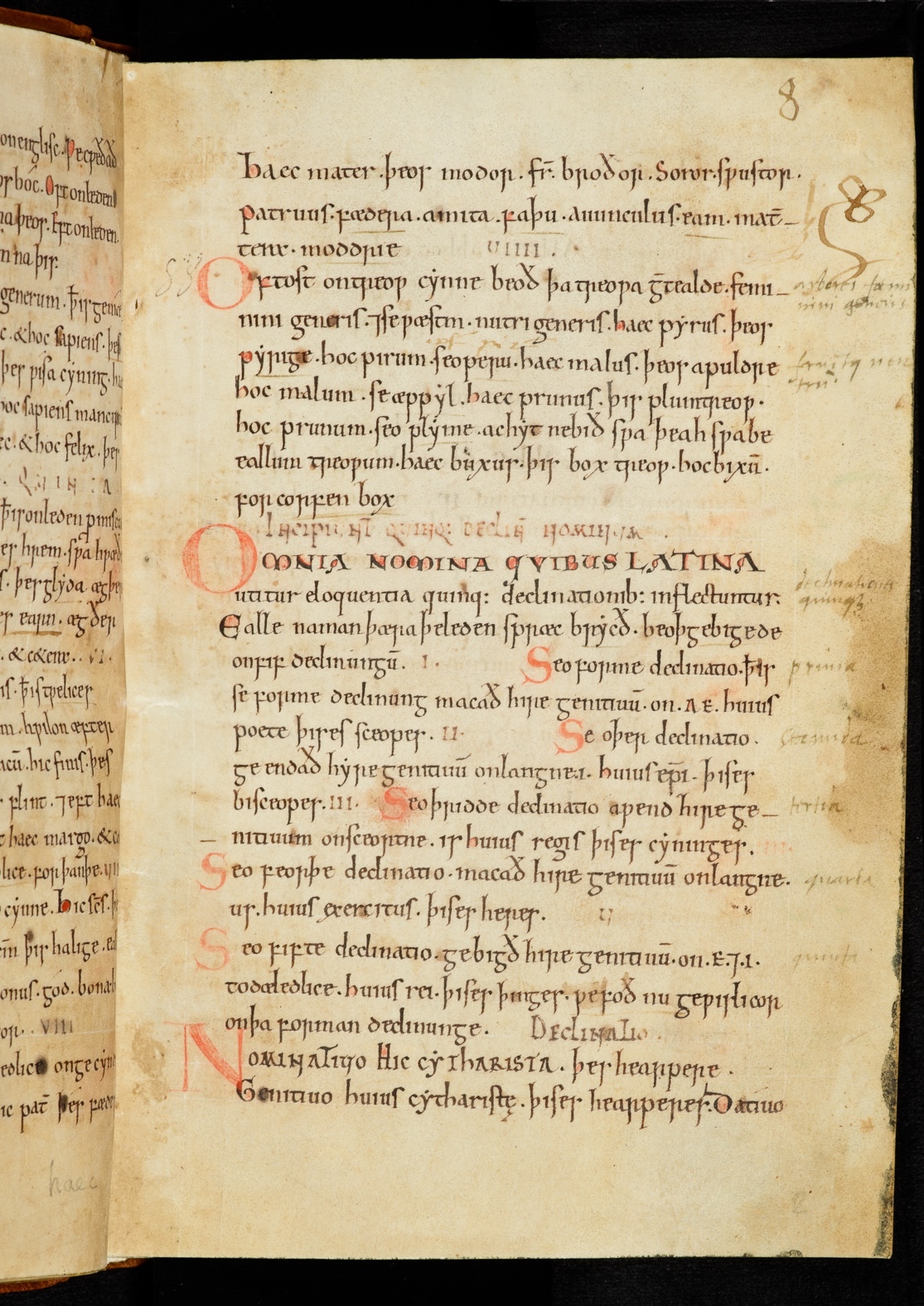

King Alfred’s literacy campaign proved considerably successful, specifically for certain part of the population, that is, ‘youth and free men who could not be used for other purposes’. One such young man was the 10th century Benedictine monk, scholar and prolific writer Ælfric of Eynsham, who wrote mainly Old English prose, but Latin, too. As a scholar and translator, he was very much aware of the complexities and nuances of language, for he claims the following in his Old English preface to Genesis:

“Nu ys seo foresæde boc on manegum stowum swiðe nearolice gesett, and þeah swiðe deoplice on þam gastlicum andgite, and heo is swa geendebyrd swa swa God silf hig gedihte þam writere Moise, and we durron na mare awritan on Englisc þonne þæt Leden hæfð, ne þa endebirdnisse awendan buton þam anum, þæt þæt Leden and þæt Englisc nabbað na ane wisan on þære spræce fadunge. Æfre se þe awent oððe se þe tæcð of Ledene on Englisc, æfre he sceal gefadian hit swa þæt þæt Englisc hæbbe his agene wisan, elles hit bið swiðe gedwolsum to rædenne þam þe þæs Ledenes wisan ne can.”

[Now in many places the aforesaid Book of Genesis is set down very densely, and yet very profoundly in the spiritual sense, and it is arranged as God Himself directed to the writer, to Moses, and we dare not write down more in English than the Latin has, nor change the arrangement, except for the simple fact that Latin and English do not have the same way of ordering language. He who translates or teaches from Latin into English, ever shall he order it so that the English follows its own idiom, otherwise it will be very misleading for anyone to read it who does not know the idiom of the Latin – translation from North, Allard, & Gillies (2011: 744-745) – my emphasis]

Being the conscientious and careful translator (and scholar) that he was, Ælfric was painstakingly translating the Latin as close to the original Latin sense as possible so that his audience got the most uncorrupted version possible of the original Genesis. It is possible, however, that his perfectionist vein was not only rooted in linguistic accuracy but also in his particular religious beliefs, being one of the most salient representatives of the Benedictine reform, a movement which advocated for a stricter adherence to the monastic rules and values. It is no wonder, then, that Ælfric was concerned about the perils of mistranslating and misrendering the Latin original.

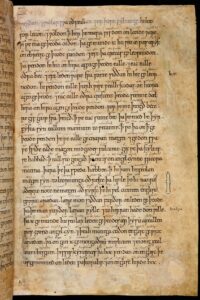

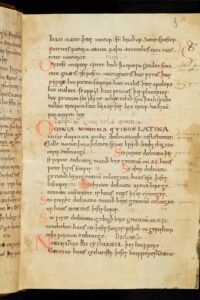

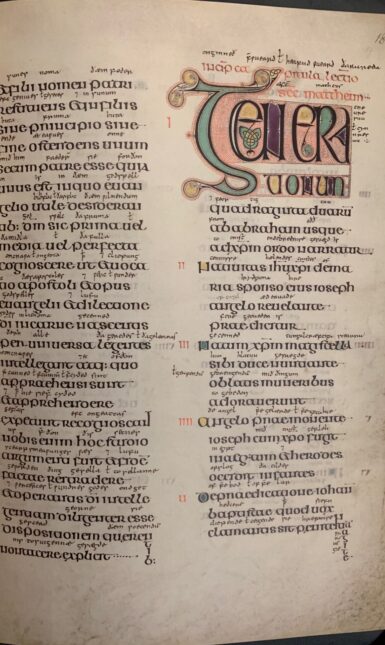

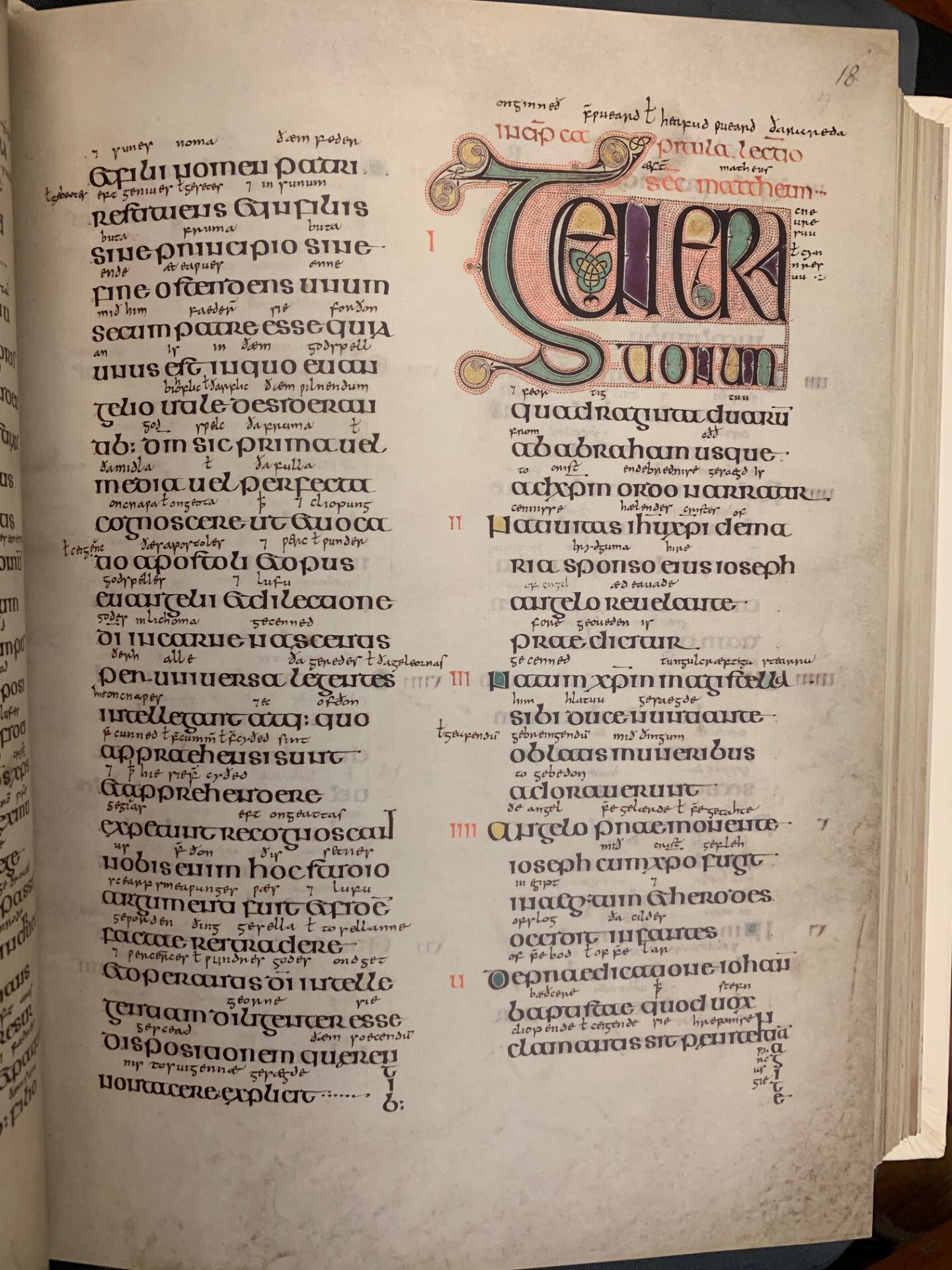

Latin, Old Northumbrian and Old Norse in the Lindisfarne Gospels

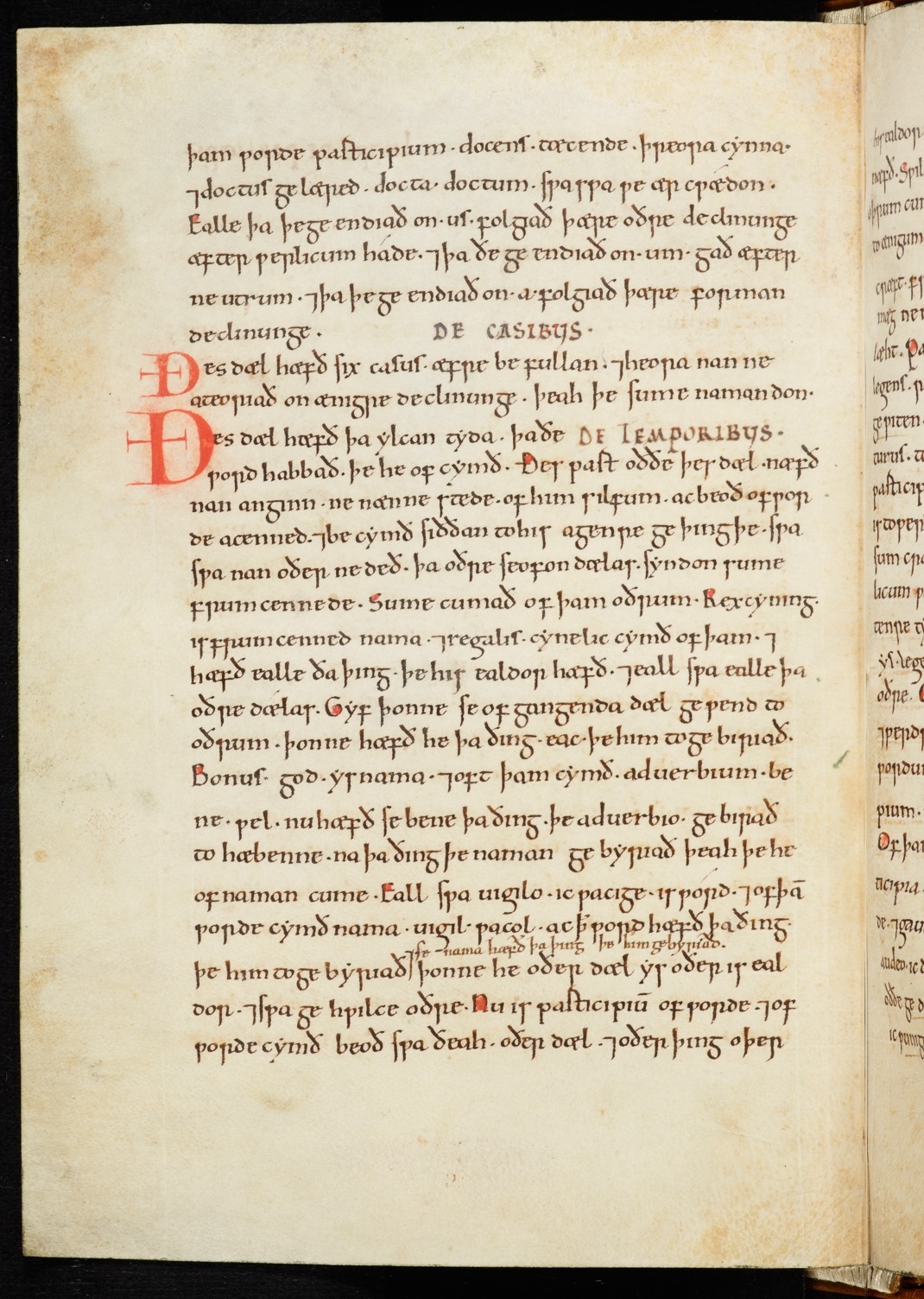

Another conscientious and careful glossator worth mentioning here was the 10th-century monk and scribe Aldred, who famously added interlinear Old Northumbrian glosses to the stunning Lindisfarne Gospels. Much like Ælfric, Aldred was also clearly aware of the nuances of both Latin and English. For my doctoral thesis, I analysed Aldred’s language, and as a result, I became fairly well acquainted with Aldred and his glossing practice. Soon, I realised that he was a very meticulous glossator.

An illustrative example that springs to mind is Aldred’s rendering of the Latin word sero. This homonymous word can, on the one hand, refer to the noun ‘evening’, but it could also be the first person singular present indicative active form of serere ‘to sow, to plant’. Given this multiplicity of meanings, Aldred chooses to provide a double gloss, thus rendering Latin sero as efern ł ic sædi (MtGl (Li) 20.8), that is, ‘evening ł I sow’. Within the verse Aldred is glossing, only the second gloss reflects the intended meaning of sero. However, this instance and many others found throughout his glosses demonstrate Aldred’s understanding of the grammatical and semantic complexity of the Latin he is translating. For more examples on how meticulous his glossing practice can be, you might want to read an earlier post I wrote about Aldred’s double and multiple glosses.

Another interesting aspect of Aldred’s glossing practice is his treatment of Old Norse borrowings. In this respect, it is important to highlight that many of these borrowings (which are non-technical and describe daily activities) occur either as single glosses to a Latin word or as the first element in a double or multiple gloss. This fact suggests that these Norse-derived words must have been very well accepted in Aldred’s dialect and idiolect, instead of still representing a foreign borrowing. Thus, the close intermingling of languages attested in Aldred’s glosses to the Lindisfarne Gospels demonstrates yet again the rich multicultural and multilingual nature of Anglo-Saxon England.

A similar picture emerged when considering the writings of Ælfric and King Alfred, as well as the inscriptions of the Ruthwell Cross and Saint Hilda’s grave marker. Although the medieval version of multilingualism which emerges from all these sources may not fully tally with our modern understanding of this term, mainly focused on proficiency, this post has hopefully revealed that Anglo-Saxon England was clearly a multicultural and multilingual country.

Sources & further reading:

Critten, R. G., and Dutton, E. 2021. “Medieval English Multilingualisms.” Language Learning: A Journal of Research in Language Studies. 71(1): 12–38.

Fernández Cuesta, J., and Pons-Sanz, S. M. eds. The Old English Gloss to the Lindisfarne Gospels: Language, Author and Context. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Gersum Project: The Scandinavian Influence on English Vocabulary (https://www.gersum.org/)

Lapidge, M. ed. 1996. Anglo-Latin Literature 600-899. London: Hambledon Press.

North, R., Allard, J., and Gillies, P. eds. 2011. Longman Anthology of Old English, Old Icelandic, and Anglo-Norman Literatures. London & New York: Routledge.

North Sea Crossings: Anglo-Dutch Books and the Adventures of Reynard the Fox (https://www.bristol.ac.uk/arts/research/north-sea-crossings/)

Pavlenko, A. ed. 2023. Multilingualism and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pons-Sanz, S. M., and Sylvester, L. eds. 2023. Medieval English in a Multilingual Context: Current Methodologies and Approaches. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

© Elisa Ramírez Perez and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2024. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Elisa Ramírez Perez and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.