More than Female Empowerment: Exercise with a 16th-century Chinese legal document

A fifteen-year-old girl is charged with licentiousness, submits a petition from jail in which she claims she is innocent, and is exonerated. While this may seem like a tale of female empowerment, a critical look at the (re)production of her petition shows that things are not that simple.

The Petition

In 1525, a petition by a fifteen-year-old girl from jail reached the desk of Emperor Jiajing (r. 1522-1566) of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). In the petition, Li Yuying claimed that she was falsely charged and sentenced to death for being an unfilial and licentious stepdaughter, exposing not only her stepmother’s crimes but also the jailors’ corruption. The opportunity to petition arose when the emperor ordered an inspection of inmates due to the life-threatening heat in summer. [1] This was a common practice in Ming China, implemented by the court to reduce the inmate population and deaths caused by the miserable jail conditions, such as overcrowding and mismanagement. During the 1525 inspection, officials reviewed ongoing legal cases to see whether they could be expedited or deserved leniency. According to the court records, seven inmates whose serious but dubious charges were reassessed and cleared. Li must be one of them if her petition indeed succeeded. [2]

The earliest record of Li Yuying’s story can be found in a book by the scholar Li Xu (1505-1593), a collection of interesting local and national information. In an entry entitled “The Petition Memorial Submitted by A Daughter to Repute Her Stepmother’s False Accusations,” Li Xu notes that he recorded the document when he saw the copy made by an erudite acquaintance. [3] This copy also included the imperial order of the reinvestigation of the case and the final verdict on it: the stepmother was found guilty of murdering Li Yuying’s younger brother and should be executed, while Li Yuying would be released and matched with a fine family.

Let’s see the main passages from the petition in which Li Yuying describes her mishaps:

"My father, Li Xiong, held the hereditary military position of baihu. Thanks to the imperial recognition of his merits in a western frontier expedition, he was promoted to the position of qianhu. My mother died when I was very young, leaving behind three daughters and a son whose name was Li Chengzu. Out of concern for his young children, my father married our stepmother, Miss Jiao. When I was eleven, Your Majesty was enthroned. Young women were recruited into palace service. Officials listed my name for selection. The Ministry of Rites considered me to be too young to serve and kindly sent me home. My father departed for Shaanxi for a military operation against banditry on the fourteenth day of the seventh month of the year Zhengde 14 (1519). He lost his life fighting the bandits. This catastrophic event fell on our family unexpectedly and caused much suffering. I am fifteen years old, and have not married. All three daughters in our family have nobody to rely on. When I felt helpless and uncertain about my future, I resorted to poetry to express my feelings. Two of the poems I composed were titled “Farewell to the spring” and “Farewell to the swallow.” (Full texts of the poems are not translated here.)… These poems reflected my feelings, allowing me to express a sense of helplessness in words. However, even though my stepmother had taken care of me, she misunderstood my intentions. The poems I wrote were taken as evidence of illicit affairs. She pressed and scolded me to the brink of despair. She then forced her brother, Jiao Rong, to report me to the Imperial Bodyguard on the false accusations of unfiliality and licentiousness. [4] Being a woman, I am not good at arguing. The official overseeing the trial distorted the truth and issued a death penalty. I had no choice but to submit to the reality. One concern was that if I objected to my stepmother, the accusation of infiliality imposed on me would be more serious."

Having established Li Yuying as a filial daughter and a girl of good character, a victim of an evil stepmother, the petition proceeds to explain what had happened in the family:

"Although my father was a military officer, he was well-versed in the classics. Thus, I was able to receive some education. [At the time of his death,] my stepmother was only twenty. Her son had just turned one. To make her son the legitimate successor to my late father’s status, she ordered my younger brother—who was only ten years old—to go to the battlefield to collect our father’s body. She probably thought that if my brother died on the journey, her plans would succeed. Fortunately, thanks to Heaven’s blessing and my late father’s spiritual protection, my brother returned safely with our father’s corpse. Although this plot failed, her evil desire persisted. She found a way to poison my brother, kill him, and bury his dismembered body. She then sold my elder sister, Li Guiying, to a powerful family as a maid, claiming to have found her a comfortable home. My stepmother also forced my younger sister to beg on the street. Her good clothes were taken away; she was subject to beating if she dared to resist. Now my stepmother falsely accused me of having an illicit affair. … The thin evidence cited by my stepmother—her groundless interpretation of those poems—has incriminated me and condemned me to death. … I have been jailed for a long time. Someone in jail, taking advantage of my situation, harassed me. I cried so hard that the whole jail was shocked." [5]

The Story of a Girl’s Story

This dramatic story attracted considerable attention after its first print (1597, by Li Xu’s family) inspired Feng Menglong’s (1574-1646) fictional adaptation in the 1620s. It even entered a monumental poetry collection compiled by the renowned scholar-official Qian Qianyi (1582-1664) in the mid-seventeenth century. This record has been used by social historians to show that women had access to education and opportunities to develop literary talents, and that women in elite families competed for survival and had agency. [6] These arguments about medieval and early modern Chinese women have already been established in women’s historiography over the past decades. In the absence of collaborative sources on this particular legal case, I think we should refrain from drawing easy conclusions and instead try to raise deeper questions to contextualize this petition and its transmission.

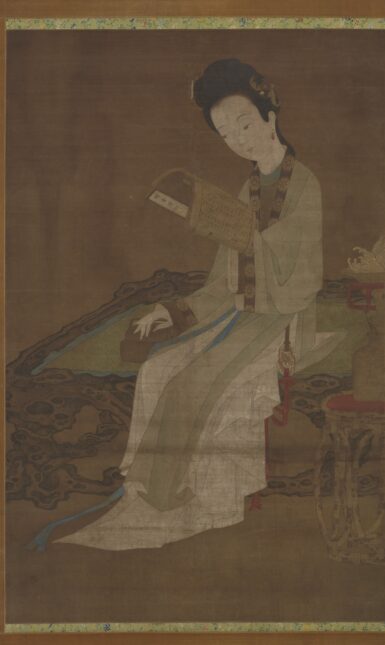

Women’s biographies and records abound in premodern Chinese sources. This phenomenon has been a blessing and also a challenge for women’s and gender historians. [7] We “discover” Li Yuying because male writers at the time found her petition interesting. While Li Xu simply copied the documents into his collection of notes, the literary giant Qian Qianyi presented Li as a female poet by including the two poems in her petition. Qian intended his work to be the definitive book on Ming-dynasty poetry, devoting several volumes to female poets in this influential compilation. He placed Li in a chapter on women of elite families, and attached a brief biography of this young woman summarizing the heinous crimes committed by her stepmother. Qian’s project reflected late-Ming public fascination with and visibility of the literary woman. She could be anyone, the wife or daughter of an official, a nun, or a courtesan. [8] [fig. 1]

In fact, Li Yuying’s petition itself reads like a work of literature, exemplifying a prominent phenomenon at the intersection of law and literary production in imperial China. [9] The text establishes the image of a properly educated and mannered girl through her own poems and her apt references to the classics. Her life events are organized around this persona at the expense of the timeline’s clarity and precision. She emphasizes that she was eligible for palace service upon the new emperor’s enthronement in 1521. We know that her father had died in 1519; he could not have foreseen the change of reign and arranged her daughter’s palace selection. How and why did the stepmother manage to enlist Li for the selection during the mourning period? The petition acknowledges that, partially, her poems reflected her desire to be married to someone whom she could rely on. As historians have pointed out, during this time period, the rise in women’s literacy and literary presence provoked severe backlash. Pursuing one’s passion, a major theme in artistic and philosophical works, also caused conservative concerns. [10] Li’s self-representation as a literary woman longing for love in the petition thus risked reinforcing the original accusation of immorality. What made her (and whoever helped her draft the petition) believe that this would strengthen her case rather than jeopardize it?

Qian Qianyi might have noticed Li Yuying through Feng Menglong’s fictional adaptation of the record. [11] While the central message of the fiction is a caution against evil stepmothers, Feng’s praise of Li Yuying also follows the tradition of promoting exemplary women’s morality and courage for didactic purposes. The end of this short fiction claims that Li Yuying’s petition appeared in a collection of exemplary women’s biographies. [fig. 3] A classical genre of didactic texts in imperial China, the tradition of compiling and reading exemplary women’s biographies not only persisted but also continued to be updated in the late imperial period. Interestingly, one such collection has been attributed to Feng Menglong himself, entitled Stories based on the Biographies of Exemplary Women. [12] But because existing editions of this book contain some material that could only have happened after Feng’s death, the authenticity of his authorship has been questioned. Nonetheless, this and many other details in the fiction demonstrate that Feng used his literary imagination to dramatize the story, fill the obvious gaps, and smooth out the incoherence in the information presented by the original petition. [13] Thus, when today’s historians continue to approach Li Yuying as a talented and heroic woman and fail to consider the nature, production, and reproduction of her petition, the world in which she resided is flattened and decontextualized.

The Historian’s Craft

The historian’s methodological advantage lies in her ability to utilize broad historical knowledge to ask meaningful questions about and with our primary sources. For example, Li Yuying’s petition tells us that her younger sister submitted the document to the court on her behalf. But based on what we know about the legal practices in the Ming, the girls would not have been able to do this through the jail walls without assistance. Li probably also received advice on how to draft this petition. These forms of help had to come from men, as they enjoyed greater access to legal knowledge, networks, and facilities such as jails.

Further, why did these men help Li Yuying? What was their relationship to her family and her stepmother? The Li family had a hereditary status in the Imperial Bodyguard system; she was also detained in its jail. According to the regulations, the Imperial Bodyguard participated in the trials that might result in heavy sentencing, while the review of the cases was carried out by specialized palace eunuchs together with legal bureaucratic offices. Still, if the Imperial Bodyguard wanted to influence the review process and keep Li incarcerated, they could do so easily through unofficial channels. Someone in the Imperial Bodyguard system and its jail wanted to see Li freed. Note that after exonerating Li, in an unusual move, the court ordered the Imperial Bodyguard to arrange a suitable marriage for her. [14] Who might have influenced the mention of her marriage prospects in the imperial order? What was the motive behind it?

These questions, even if never answered in this case due to a lack of primary sources, make an interesting and meaningful exercise for the historian because they not only take into consideration the complexity of this source but also, by interrogating the source’s production and reproduction, connect it to broader questions in institutional history and gender history.

Footnotes

[1] In imperial Chinese political culture, natural disasters were often interpreted as signs of poor governance. Emperors and officials used such occasions to implement or propose policy changes or to issue benevolent measures.

[2] Ming Veritable Records Jiajing 4/5.

[3] Li Xu 李詡, Jie’an Laoren manbi 戒庵老人漫筆 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1982), 122.

[4] The Imperial Bodyguard had mixed, evolving roles in the Ming, including policing and military functions. The households within this system were also subject to regulations separately.

[5] Li Xu, Jie’an Laoren manbi, 120-121. The sources presented in this blog are all translated by this author.

[6] For example, Wang Xueping, “Mingdai Li Yuying an de shehui xingbie fenxi 明代李玉英案的社会性别分析.” Journal of Social Science of Harbin Normal University No. 89 (Issue 4, 2025): 135-140. Legal scholars have used this record to discuss the procedure of “summer trial” in the Ming judicial system, with no particular interest in its gendered aspect.

[7] Susan Mann, “Presidential Address: Myths of Asian Womanhood.” The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 59, No. 4 (Nov., 2000): 835-862.

[8] Qian Qianyi 錢謙益, Liechao shiji xiaozhuan 列朝詩集 (Xuxiu Siku quanshu ed.) (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2002), 359. On the gender politics of women’s poetry canonization, see Grace Fong, “Gender and the Failure of Canonization: Anthologizing Women's Poetry in the Late Ming.” Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR), Vol. 26 (Dec., 2004): 129-149.

[9] On the blurred boundaries between legal documents and literature, see Robert Hegel and Katherine N. Carlitz eds., Writing and Law in Late Imperial China: Crime, Conflict, and Judgment (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017).

[10] On both topics, see Dorothy Ko, Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-Century China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994); “Pursuing Talent and Virtue: Education and Women's Culture in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century China.” Late Imperial China, Volume 13, Number 1(June 1992): 9-39.

[11] Feng Menglong 馮夢龍, Jingshi hengyan 警世恆言, ch. 27.

[12] Feng Menglong, Lienuzhuan yanyi 列女傳演義 (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1990).

[13] Feng Menglong was interested in the legal institutions and their social impacts. He wrote any stories on this topic, some of which adapted real legal cases.

[14] The Ming court regulated the households of imperial guards and police to some degree, including the expectation for marriages among them.