“Layla, you got me on my knees, Layla…”

What is my favourite medieval Persian poet Nezami (d. 1209) doing on the cover of an English rock album? Why was Eric Clapton so attracted to the romance Layla and Majnun that he composed his seminal song Layla?

A Persian-British Artistic Liaison

“Layla, you got me on my knees” is a familiar refrain from the famous song by the British rock star Eric Clapton, who composed it for Pattie Boyd, the wife of George Harrison, the guitarist of the Beatles. Clapton was passionately in love with Pattie and his intense love brought him to the edges of insanity, taking refuge in drugs, even heroin, till he finally found his way to music through poetry. It was the medieval romance Layla and Majnun by Nezami that inspired him to return to art, creating the seminal album Layla. His friend Ian Dallas gave him a free translation of the romance by Rudolf Gelpke (1928-1972) and Clapton immediately identified himself with the star-crossed lover Majnun, his agonies, longings, frustrations, intense love-madness and his poetic virtuosity.

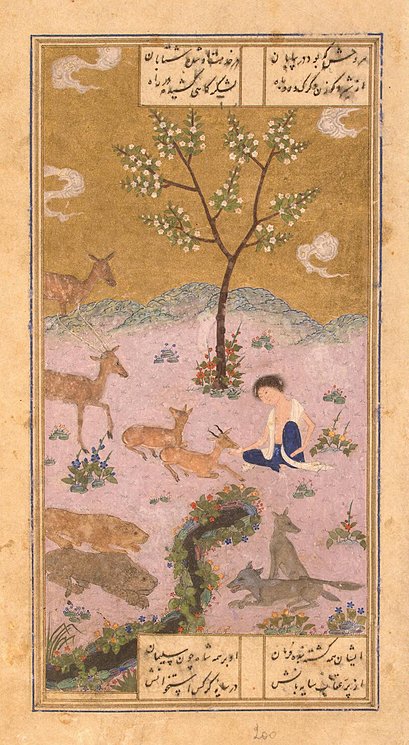

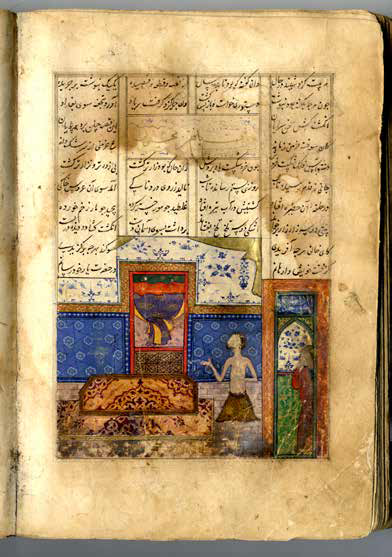

Nezami wrote the romance in 1188. Long before Nezami, dozens of anecdotes circulated on the remarkable love between Majnun and Layla, on Majnun’s insanity, self-disinterested love, wanderings in the desert, living with wild and tame beasts, and above all on his love poetry. All these loose anecdotes were written mainly in Arabic, but Nezami created a courtly epic in Persian, depicting Majnun’s life from birth to death. The story has a simple plot. Majnun falls in love with Layla at an early age. He composes poetry for her, revealing his love in a society where love had to be hidden. His father asks Layla’s hand but Layla’s father turns him down. This rejection drives Majnun mad and he seeks refuge in the wilderness. Layla is married off to another man. Majnun stays in the desert where he composes love songs and lives with animals. Majnun has idealized Layla to such a degree that when Layla’s husband dies and she is available, Majnun rejects the physical Layla, preferring her imagined, transcendental version. Layla and Majnun die without consummating their love. Majnun’s peculiar decision resembles how an artist raises reality above and beyond himself. For Clapton, Pattie was perhaps ultimately someone he wanted to worship from a distance, longing for her, rather than to be with her.

Clapton read the popular translation by Gelpke, a small book adorned with several exquisite medieval Persian paintings. Gelpke’s translation is far from literal, but it captures the soul of the original, making it available for a wide audience. It was not the first translation into English. Layla and Majnun attracted the attention of Isaac D’Israeli (1766-1848) so much that he rendered it into English in 1797. This adaptation was the basis for the opera Kais, or Love in the Deserts: An Opera in Four Acts by William Reeve. It was “performed with unbounded applause at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane.” Gelpke’s free adaptation is a perfect example of how a text for the broad public leads to availability of such a medieval work, inspiring people in ways that a scholarly work can hardly achieve.

Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs

It is amazing to have a Muslim poet from twelfth-century Persia on an album created in Florida in the United States. It is even more remarkable that Nezami’s name is mentioned as a fellow song writer. Clapton credits Nezami for the fifth song “I am yours” of the album Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs which was released in 1970, one of the masterpieces in rock history. This is quite unique. “I Am Yours” consists of 47 words, repeated three times, and it is based on Nezami’s romance. I could not find a specific passage but all of the elements in the song are scattered throughout the romance of about 5000 couplets. Although many metaphors Clapton used are universal, they are part of the Persian love mysticism, in which the obsessed lover sees the beloved everywhere. Love sharpens the senses to such a degree that any sensory perception involves the beloved. The lover is totally absorbed in the beloved’s thoughts:

I am yours.

However distant you may be,

There blows no wind but wafts your scent to me,

There sings no bird but calls your name to me.

Each memory that has left its trace with me

Lingers forever as a part of me.

I am yours.

Eric Clapton performing "I am yours".

Anything the lover experiences reminds him of the beloved. The wind is the dispatcher of the beloved’s scent, the nightingale sings the beloved’s name. The beloved is unyielding in Persian tradition and the lover must console himself with any sign and token from the beloved. Living in separation, her memory becomes part of the lover to such an extent that it becomes part of the lover’s identity. Similar passages can be found in Nezami’s romance:

0h eastern wind, rise at the morning glow

and attach yourself to the tip of Layla's curl.

Say to her that the one who was robbed by the wind,

has fallen in the dust of your road,

He is imploring your breath from Zephyr;

he is telling his anguish to the earth’s dust.

Send a breeze from your land,

give him a handful of dust as a memory.

Everyone, who does not blow like a breeze towards you,

is not worth the wind, let alone the dust.

Clapton composed “Layla” but why did he credit Nezami with the song “I am yours”? The song is not a literal translation of Nezami, but Nezami must have been the source of inspiration. Clearly, Clapton wanted to express his appreciation and to guide his audience to the romance, to actually read this amazing story, which changed his life. Clapton’s example shows how art and poetry transcend cultural, religious, and ideological beliefs, crossing time and space, inspiring people irrespective of their backgrounds. Nezami’s poem is a lucid example of how a simple story acquires universal fame, becoming part of the world literature. So what are the ingredients of this story that has attracted generations of artists through the ages to use this romance for a wide range of purposes? Nezami’s poem has been creatively imitated over hundred times in different languages.

Love or betrayal

There are several reasons why Clapton loved the romance. The first is the universal theme of unrequited love. This is a story of longing, perhaps of masochistic longing, but one that turns the lover to a spiritual illumination. Clapton fell desperately in love with Pattie and any move to win her love would have been a betrayal of his friend George Harrison. Clapton’s relationship to Pattie resembles Majnun who from a distance watches how his beloved Layla is married to Ibn Salam. Both Majnun and Clapton compose love songs for their beloved. Majnun remains faithful to Layla. And Layla, married against her will, remains chaste. She even arranges nightly trysts with Majnun, but they never touch each other. Thus she never betrays her husband, but she also never betrays Majnun. Despite love’s burning desire, Majnun and Layla never transgress the limits. For both Clapton and Majnun the unrequited love grows to obsession, which generates poetry. Majnun’s real name is Qays but he became so ‘possessed’ (majnun) that his sobriquet become his real name.

The second aspect is the accessibility of the romance. Clapton finds solace in the character of Majnun and the torments of his impossible love. In Nezami’s romance, love is depicted as pain, a fire which burns Majnun, turning him to a madman, but it also inspires him to become a poet. Similarly Clapton created poetry from his pain, obsession and insanity. Both Majnun and Clapton express their woes and agonies in lyrics, complaining of love’s impact on their body and soul. It is this poetry of love and longing that elevates their anguish, suffering, and insanity to expressive art. Separated from the beloved, both Majnun and Clapton desire to communicate, even to touch the beloved through poetry. In a sense, if their poetry reaches the beloved, they themselves will have reached the beloved. Or as the Persian poet Amara Marvazi from the end of the tenth century put it superbly:

اندر غزل خویش نهان خواهم گشتن

تا بر لب تو بوسه زنم چونْش بخوانی

I’ll hide myself in my poem

To kiss your lips when you recite it.

The poetry is a direct physical medium to contact.

The paragon of love

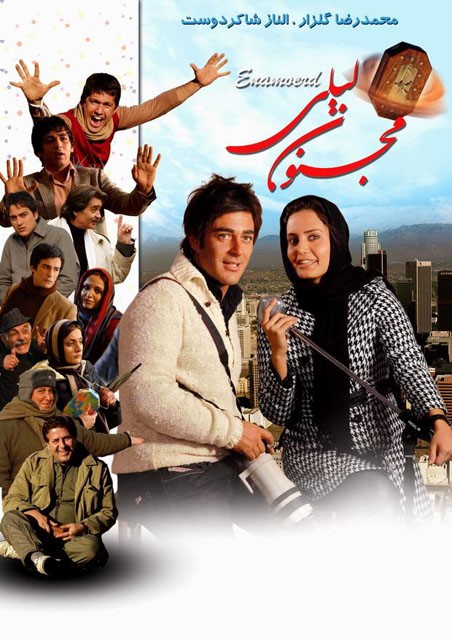

For me, a fascinating aspect is to see the name of my treasured poet Nezami on the Album, a source of inspiration for a modern rock song, which shows that the values of love transcend cultural boundaries. The romance exhibits the portrayal of characters in their deepest emotional conditions, referring, for instance, to Layla as an embodiment of an incarcerated woman, trapped in a social web of laws, her anxieties, and how she tries to express her feelings without transgressing religious and social norms. Layla’s experiences are recognizable in women’s positions in modern Islamic societies. The same applies for Majnun, who is a paragon of love. His self-disinterested love has become an example for many people. Even today, their love is still celebrated in pop songs and operas, paintings, novels and films.

Further readings:

For my references to Clapton I am indebted to the fascinating study of Menocal.

Gelpke, R. 1963. The Story of Layla and Majnun, English translated (1966) by E. Mattin and G. Hill. London: Bruno Cassirer.

Khairallah, A.E. 1980. Love, Madness and Poetry: An Interpretation of the Maǧnūn Legend. Beirut: Beiruter Texte und Studien.

Menocal, M.R. 1994. Shards of Love: Exile and the Origin of the Lyric. London: Duke University Press.

Seyed-Gohrab, A.A. 2003. Laylī and Majnūn: Love, Madness and Mystic Longing in Niẓāmī’s Epic Romance. Leiden: Brill.

Seyed-Gohrab, A.A. 2019 forthcoming. “Longing for Love: The Romance of Layla and Majnun.” In Wiley-Blackwell Companion to World Literature. General Editor Kenneth Seigneurie, London: Wiley-Blackwell.

Seyed-Gohrab, A.A. in Encyclopaedia Iranica, under Leyli o Majnun,

Talattof, K. and Jerome W. Clinton. eds. 2000. The Poetry of Nizami Ganjavi: Knowledge, Love, and Rhetoric. New York: Palgrave.