In the eye of the beholder. Female perspectives on the importance of beauty

The famous male author Baldassare Castiglione wrote that "much is lacking to a woman who lacks beauty". But what did women themselves think about this topic?

My previous blog post focused on male perceptions and expectations of female beauty. It showed that male authors attached great importance to female beauty, but also criticized and ridiculed women who tried to enhance their appearance with makeup. This blog will pay attention to what women themselves thought about the importance of female beauty. Not unlike modern-day discussions about makeup, body positivity, and feminism, there were many perspectives. Some women considered beauty to be the most valuable quality a woman had, while others stated that other things were more important in order to gain love and respect.

Beauty is a valuable commodity

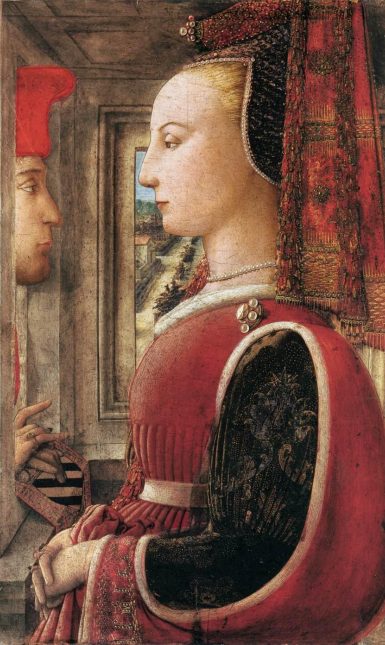

The first perspective that needs to be taken into account, is that of the marriage market. In Renaissance Italy, women themselves played a very active role in settling good marriages for their children or wards. The letters these women wrote, show that the marriage market was very competitive and favored young and beautiful women. The Florentine businesswoman Alessandra Macinghi Strozzi (c. 1408-1471) literally describes the prospective brides for her sons as merchandise [mercantanzia]. In her letters, the appearances of these women are discussed in detail, including their figure, length, facial features, hair color, and skin color. Her sons were rather picky, rejecting women based on their appearance. Strozzi put much effort into convincing them, noting that “according to me, her looks don’t compromise the match as, in my judgment, they’re above average.” She however agreed with her sons that the most important quality of a wife is that she is beautiful. This view was shared by another female author as well. The marchioness of Mantua, Isabella d’Este (1474-1539) often tried to arrange marriages for the young court ladies that were placed under her care. On one of these girls, Isabella remarked that

Diana is not the prettiest girl in the world, and is not likely to find a suitable match. As virtuous and well-mannered as the girl is, you know that in these times, of the three great qualities one seeks in marrying a woman, virtue is valued the least; so if she is not better supported by Messer Francesco and his brothers [i.e. given a bigger dowry], we very much fear that the sweet young lady may grow old in our house.

Beauty is not enough to win a man’s love

Not everyone agreed that beauty was the most important thing a woman had to offer. The Paduan noblewoman Giulia Bigolina (c. 1518- c. 1569) wrote a prose romance called Urania in which she repeatedly suggests that beauty is not enough to win a man’s enduring love and respect. The book is dedicated to a man called Bartolomeo Salvatico, and in the introduction, Bigolina explains that while she first wanted to give him a portrait of herself as a gift, she later decided that it would be better to write him something. As a sign of her virtue and learning, a book would be a much greater reminder of her love and respect for him than a picture of her face would be. The same moral is reflected in the book’s main story about the noblewoman Urania, who is learned and virtuous as well as beautiful. One of her admirers, with whom she is in love, suddenly abandons her because he encounters a woman who is much less virtuous, but exceeds her in beauty. In the end, however, because of her intelligence and courage, Urania is capable of heroically saving this man from a precarious situation, and the two finally get married. The same moral, the value of virtue over beauty, is also proven by means of an anti-example. Urania’s success in convincing her admirer of her worth is juxtaposed by the story of a duchess who fails to do so. This woman tries to seduce a prince by sending him a painting of her naked body, but she fails, because her beauty only reminds the prince of a different woman with whom he was already in love, and whom he now decides to marry. All these different storylines show that beauty alone is insufficient to win a man’s love and respect.

Diamonds are a girl’s best friend

While the previous examples mostly discussed women’s “natural beauty”, including their facial features and figure, there were many different opinions about whether women should try to enhance that beauty. Women who wore makeup and luxurious or seductive clothing were often criticized by members of the clergy. In order to increase public morality, secular and religious authorities sometimes issued sumptuary laws which forbade women to wear particular fabrics, furs, or other embellishments. In 1453, the Bolognese noblewoman Nicolosa Sanuti (d. 1505) became famous for demanding the repeal of one of these sumptuary laws. In a letter to the cardinal who had issued the law, Sanuti argued that women deserve to decorate themselves as a reward for their many virtues. She mentioned many famous women, from both classical antiquity as well as her own time, who had shown the worth of the female sex, in their fidelity, bravery, wisdom and learning. Importantly, however, jewelry also serves a more vital goal. According to Sanuti, within the gendered hierarchy of her own society, a woman’s appearace it is the only outward sign of her worth and value:

Let virtue attain her reward. Let not the rights of the humbler sex be snatched away by the injustice of the more powerful. State offices are not allowed to women, nor do they strive for priesthoods, triumphs, and the spoils of war, for these are the customary prizes of men. But ornaments and decoration, the tokens of our virtues - these, while the power is left us, we shall not allow to be stolen from us.

As women were banned from performing any important political, religious or military functions within society, paying attention to their appearance was much more important for women than for men. Gold, jewels, and other adornments, Sanuti argued, were “testimonies to virtue” and “heralds of a well-instructed mind”.

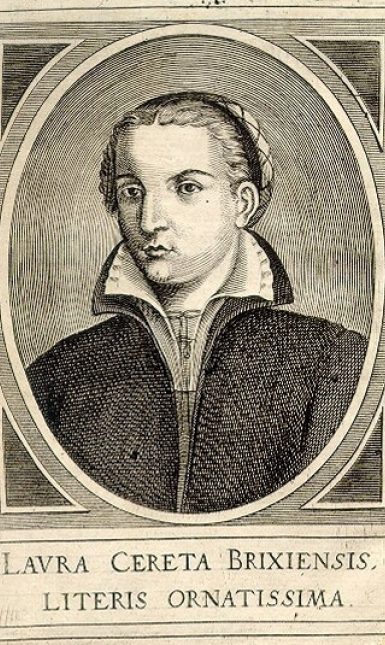

Learned ladies do not need makeup

Another female author completely disagreed with Sanuti’s argument. Laura Cereta (1469-1499) was the daughter of magistrate, and had enjoyed a very thorough humanist education. She became a widow at the age of 16 and devoted herself to literary studies for the remainder of her life. Cereta was one of the most famous female writers of the fifteenth century: she gave public lectures and her autobiographical collection of letters, the Epistolae familiares, circulated among scholars. These letters, written to family and friends as well as fictional addressees, are actually more like essays, and many of them discuss topics relating to the position of women in society. According to Laura Cereta, women need to preoccupy themselves with their studies rather than their appearance if they want to prove their worth and be taken seriously. In one letter, Cereta argued that all women have the freedom to acquire an education, but this requires hard work and the ability to ignore the distractions of other less serious things. She scorned those women who “only worry about the styling of their hair, the elegance of their clothes, and the pearls and other jewelry they wear on their fingers”. These women only care about parties, dancing, and makeup, “defacing with paint the pretty face they see reflected in their mirrors”. Women who want to achieve more in life, Cereta stated, “should restrain their young spirits and ponder better plans”. She herself took great pride in her modesty, describing herself as “a woman who is humble in both her appearance and her dress” because she was “more concerned with letters [i.e. her studies] than with adornment”. These are the things that will bring a person honor, she says, not just in this life, but after death as well.

This short overview of female opinions on the importance of beauty has shown that there were many perspectives. Historian Daniela De Bellis has argued that the topic of female beauty posed a serious dilemma for women in in the Renaissance. Women needed to enhance their appearance in order to find a husband, reflect their social status, and conform to societal expectations in general. However, by only paying attention to their appearance, women also worked to confirm the traditional societal vision of their role. If women wanted to be taken seriously, early “feminists” like Bigolina and Cereta argued, they needed to let their learning, rather than their beauty, speak for itself.

Translations and further reading:

Bigolina, Giulia, Urania. A Romance. Edited and translated by Valeria Finucci (Chicago 2005).

Cereta, Laura, Collected Letters of a Renaissance Feminist. Transcribed, translated, and edited by Diana Robin (Chicago 1997).

De Bellis, D., ‘Attacking sumptuary laws in Seicento Venice: Arcangela Tarabotti’ in: L. Penizza ed., Women in Italian Renaissance Culture and Society (Oxford 2000).

D'Este, Isabella, Isabella d'Este. Selected Letters. Edited and translated by Deanna Shemek (Toronto 2017).

Kovesi Killerby, C., ‘“Heralds of a well‐instructed mind”: Nicolosa Sanuti’s defence of women and their clothes’, Renaissance Studies 13.3 (1999).

Robin, D., ‘Humanism and feminism in Laura Cereta’s Public Letters’ in: L. Panizza ed., Women in Italian Renaissance Culture and Society (Oxford 2000).

Strozzi, Alessandra, Selected Letters of Alessandra Strozzi. Translated with an introduction and notes by Heather Gregory (Berkeley/ London 1997).

© Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Marlisa den Hartog and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.