Homicidal Hogs: Murderous Pigs on Trial in Medieval France

A sow eating a baby from a cradle: a horrifying image in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales may have roots in actual medieval history.

An infanticidal sow on the wall of the Temple of Mars

In Geoffrey’s Chaucer’s The Knight’s Tale, the Knight describes a temple dedicated to Mars, the walls of which are covered in a mural. The mural depicts all sorts of crimes and sins committed under the influence of Mars, including the infanticide by a pig:

A thousand slayn, and nat of qualm ystorve

The tiraunt, with the pray by force yraft

The toun destroyed, ther was no thyng laft

Yet saugh I brent the shippes hoppesteres

The hunte strangled with the wilde beres

The sowe freten the child right in the cradel

The cook yscalded, for al his longe ladel (Geoffrey Chaucer, The Knight’s Tale, ll. 2014-2020)

[A thousand people killed, and not died because of the Plague

The tyrant, with the prey taken by force

The town destroyed, not one thing was left

Yet I saw that ships burned, dancing (on the stormy sea)

The hunter strangled by wild bears

The sow eating a child right from the cradle

The cook struck down, even though he had a big spoon]

Chaucer’s description of the mural appears a strange mix that ranges from actual atrocities of warfare (thousands of dead, destroyed towns, burning ships) to seemingly absurd and slightly ironic events (hunters strangled by bears, children eaten by sows and cooks being killed despite having oversized eating utensils). The murderous sow, however, seems to be firmly rooted in historical fact and there appears to have been an intriguing, contemporary analogue to Chaucer’s wall painting in 14th-century France.

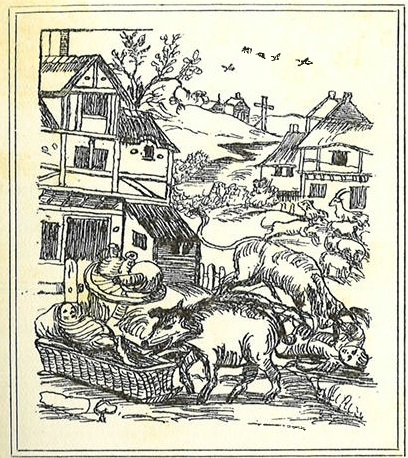

A sow eating a baby from the cradle, reproduced from a 17th-century original, on the title page of Evans (1906)

A wall painting of a swinish slayer in Falaise, France

Animal historian E. P. Evans describes how, in 1386, a pig was executed in the French city of Falaise for chewing off the limbs and face of a three–year-old baby, who was lying in its cradle at the time. The execution and the pig’s crime were represented on a fresco on the wall of the Church of the Holy Trinity in Falaise, but, due to whitewashing of the walls in the 19th century, the fresco no longer exists. However, Evans added a reconstruction of part of the fresco (“not a reproduction of the original picture, but a reconstruction of it according to these descriptions”; Evans, p. 16) as the frontispiece of his book The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals. The reconstructed fresco, intriguingly, shows how the sow was dressed up in human clothing as it was publically maimed and hanged:

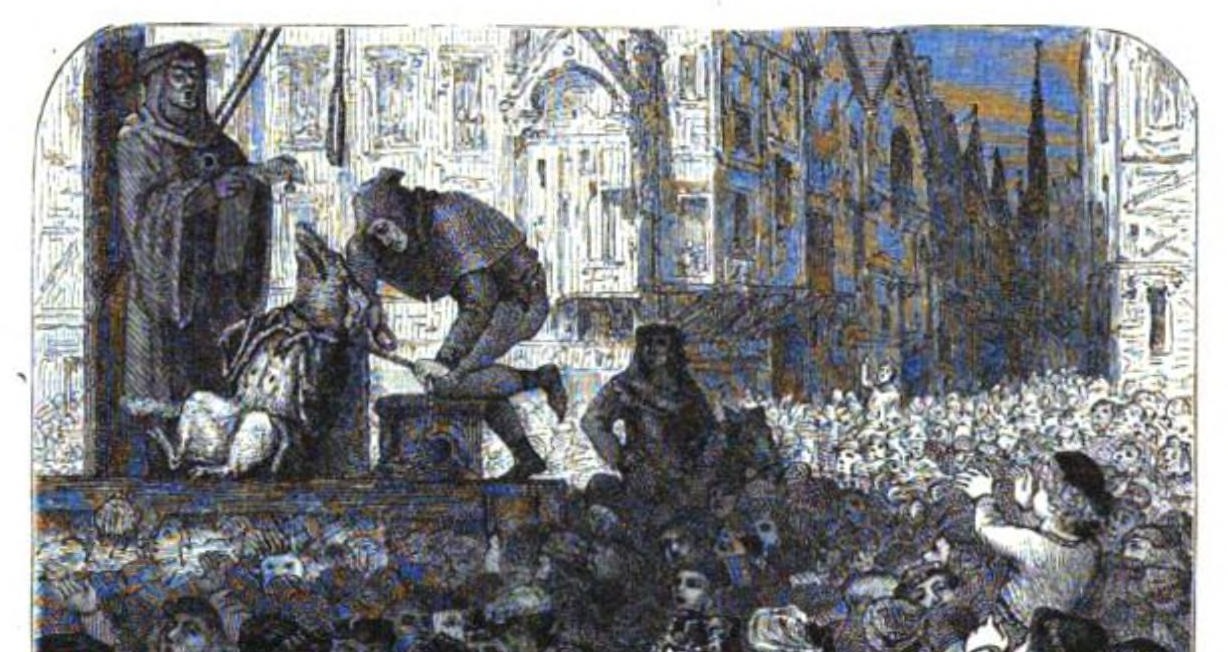

19th-century reconstruction of 14th-century mural, showing the execution of a pig.

“Here we have a strict application of the lex talionis, the primate retributive principle of taking an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. As if to make the travesty of justice complete, the sow was dressed in man’s clothes and executed on the public square near the city-hall at an expense to the state of ten sous and ten deniers.” (Evans, p. 140)

This Falaise incident was certainly not unique and Evans mentions various similar piggy-perpetrators who were hung for killing babies.

Homicidal hogs on trial in medieval France

In his ‘Chronological List of Excommunications and Prosecutions of Animals from the Ninth to the Nineteenth Century’, Evans lists no fewer than 25 cases of pigs being prosecuted, often for killing infants, between 1250 and 1500. In this, swine far outrank any other animal in Evans’ list, which also includes such cases as a cock burned at the stake for laying eggs in 1464 and various caterpillars and weevils being prosecuted for damaging vineyards and gardens. Most of the cases of prosecuted pigs derive from medieval France, which may reflect an imbalance in the source material that Evans had looked at.

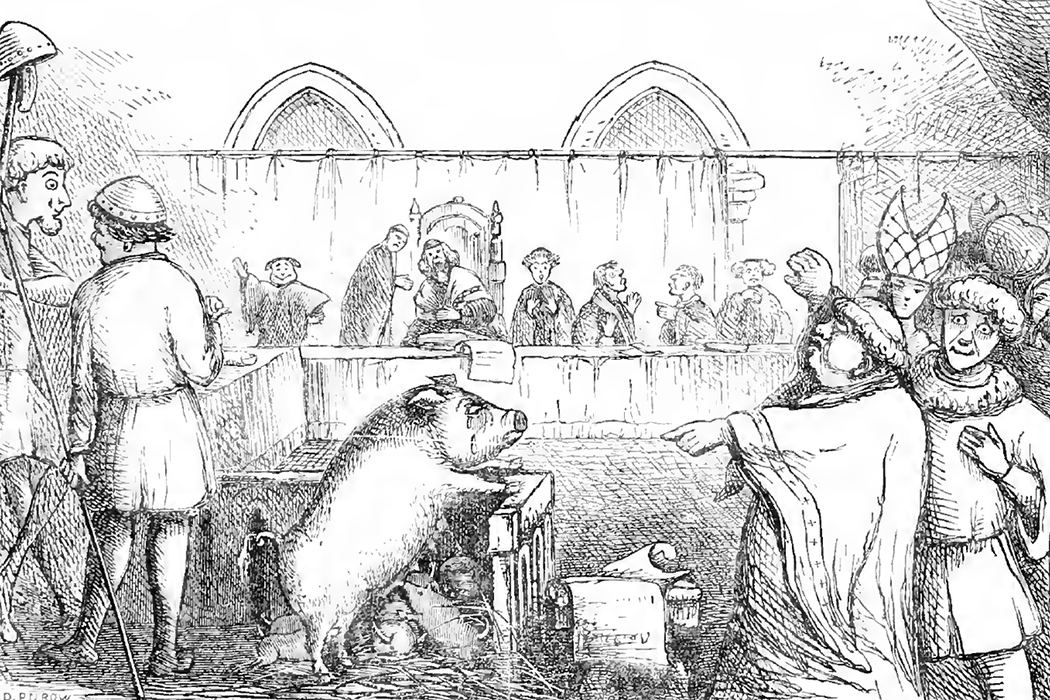

Medieval pig on trial (Wiki commons)

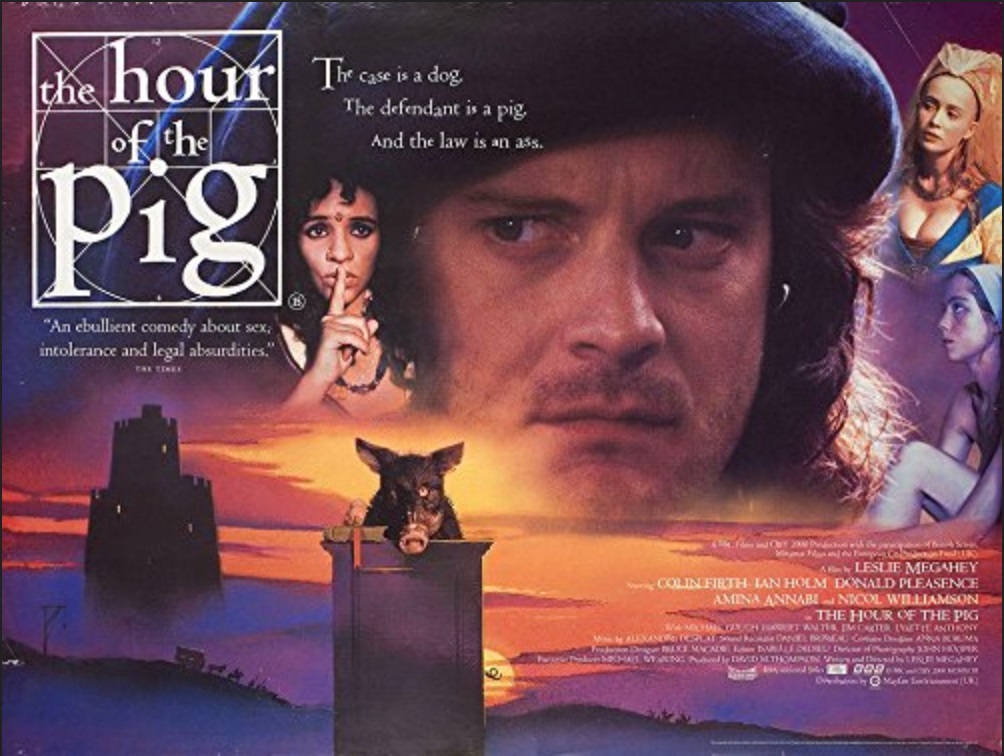

An interesting feature of these pig prosecutions is that the animals appear to have been treated in a fashion similar to human criminals. Not only were they publicly hanged at the gallows, they would also spend time in prison and there were even court cases which decided on the guilt and punishment of the animals involved. In 1379, for instance, three sows were sentenced to death by a judge and jury for killing the swineherd and his son. At the trial, it was also decided that the rest of the herd (who “had hastened to the scene of the murder and by their cries and aggressive actions showed that they approved of the assault, and were ready and even eager to become participes criminis”, Evans, p. 144) should be arrested as accomplices and sentenced to the same penalty. As luck would have it, the herd was eventually given a pardon after the friar of the priory to whom the swine belonged had written a petition to the duke.In these court cases, the accused pigs, like their human counterparts, could even be defended by lawyers. In fact, in 1993, a Hollyood film featuring Colin Firth depicts the story of a falsely excused pig in 15th-century France who eventually is acquitted thanks to the Firth’s character, who is based on an actual animal lawyer Barthélemy de Chasseneuz (1480–1541).

Poster of The Hour of the Pig (1993), starring Colin Firth (the movie appeared in the US as The Advocate)

In conclusion, let me return to Chaucer’s Knight’s Tale and its infanticidal sow. Perhaps Chaucer, who had visited France on various occasions, had heard of the murderous pig in Falaise or had even seen its fresco; or he may have heard of similar cases in France (or England). At any rate, the image does not appear to have been as far-fetched, ironic or absurd as it may first have seemed.

Bibliography

E. P. Evans, The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals (London, 1906)

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.