Health and Healing in the Norse World: A Glimpse into Medieval Scandinavian Medicine

The Vikings, often romanticized as fearsome raiders, were also adept navigators, traders, and settlers. But beyond the swords and sails lies another fascinating aspect of their lives: how they understood and managed health and healing.

I have just started a PhD at the Faculty of Archaeology in Leiden to investigate Viking healthcare. In this blog, I will outline mainly the results of my research master's, carried out at Lyon, which focused on the same topic. We delve into the practices of care and health among the Vikings and Norse people from approximately 700 to 1100 CE in North-West Europe and Iceland. This exploration offers an introductory view of their approach to well-being, showcasing their practice and cultural beliefs.

Who are the Norse people?

In my definition, the Norse peoples are, during the medieval ages, 800-1100 CE, the individuals inhabiting the Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish lands. Later, Icelanders are also included in this definition. The Norse unity of these various territories was already evident through a shared linguistic similarity. Moreover, it is believed that communication among the different peoples sharing this linguistic origin was relatively simple, to the extent that a single term was used to describe their language: dönsk tunga ("Danish tongue") or norrön tunga ("Norse tongue") in Old Norse (Blindheim et al., n.d.).

In addition to linguistic proximity, there is also a shared institutional, economic, and social framework. Indeed, these societies remained very similar in terms of political organization, characterized by a clan-based regency system (Boyer, 2004), which persisted until the 12th century, even in overseas colonies such as Iceland or in the Anglo-Saxon or Early English territories.

As such, the emergence of the Viking Age is shared across all Scandinavian societies, around 793 CE. This date is commonly considered as the beginning, attested by a Viking raid on Lindisfarne by Christians monks. The term "Viking" originates from Old Norse, where víkingr (masculine), plural: “víkingar” refers to a person and víking (feminine) to an activity (Bauduin, 2018). Derived from vík ("bay"), it suggests Vikings were pirates from bays (Blindheim et al., n.d.) who later engaged in trade, raids, and conquests. Alternatively, it may stem from vicus or wik (trading settlements) or vig ("combat") (Bauduin, 2018), highlighting their links to exploration, trade, and warfare.

Thus, there was a strong cultural proximity between the various Viking groups, even though they did not originate from the same territories. Within each group, it is interesting to observe that there are both commonalities and divergences (Boyer, 2004). Subsequently, they developed distinct cultures within each group, stemming from a shared cultural foundation.

Even though this cultural foundation is a common factor, their lifestyles, culture, and social lives—both in their place of origin and in their experiences abroad—differ. These aspects are influenced by various social factors (housing, food, etc.) and the diverse geographic characteristics of the regions studied. I believe it is essential to have a foundational understanding of these aspects in order to comprehend this subject, because their environment, including both geography, climate as well as their habitat and activities, directly influenced their health. Therefore, identifying what they were facing allows us to understand their health conditions and, ultimately, to establish a perspective on their care practices.

Material to investigate medieval Norse medical knowledge

So how do we study Viking healthcare? In the absence of detailed written sources, archaeological materials, such as artifacts, bones that have evidence for healed trauma (or, at least, evidence of trauma), and medicinal plants that were consumed or cultivated, are the elements that were closest to these peoples. Prioritizing such data is essential.

The analysis of bones and teeth can reveal the disorders faced by the Vikings: diseases, fractures, war injuries, bacteria, parasites, and even potential nutritional deficiencies. It can also provide insight into the effectiveness of care given to the injured or sick: were broken bones treated well? Did death occur due to a lack of care or because treatments were ineffective? The wear on teeth, caries, or evidence of abscesses can provide information about both dental and overall health or nutritional differences in different locations.

Plant remains, such as bark and seeds found at archaeological sites, may have been naturally present or imported. This suggests that humans may have used them for various purposes, such as food, medicine, rituals, or crafts.

Health and healthcare in the Viking Age, first results

During the early stages of my research master at Lyon, I encountered a big difficulty because there was a lack of bone material that had evidence for healed trauma. This lack of material can simply be explained by the limited time I had available to access sources during the two-year research master's program. Conversely, I was able to inventory many individuals who had experienced trauma. However, only one healed fractured tibia (Thráinn Thórðarson et al., 2014) was finally inventoried, which demonstrates that medical care could have been provided. This indicates that the Norse people were capable of surviving fractures and, more importantly, able to treat them. Today, since the beginning of the PhD research, with more time, experience, and a larger network, it has been possible to inventory many additional cases of healed bones scattered around in museum collections or excavation reports like the healed-Femur, 800-1100 CE, from the Swedish Museum of History.

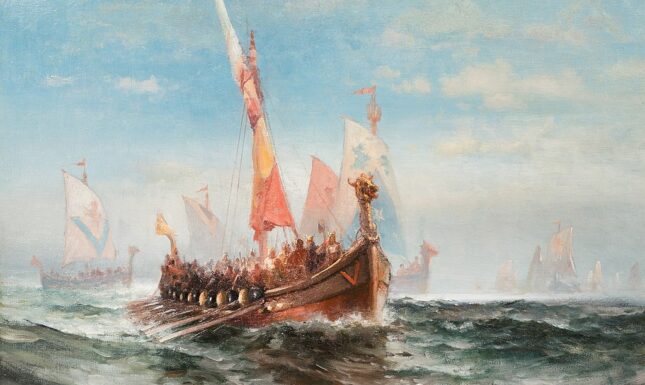

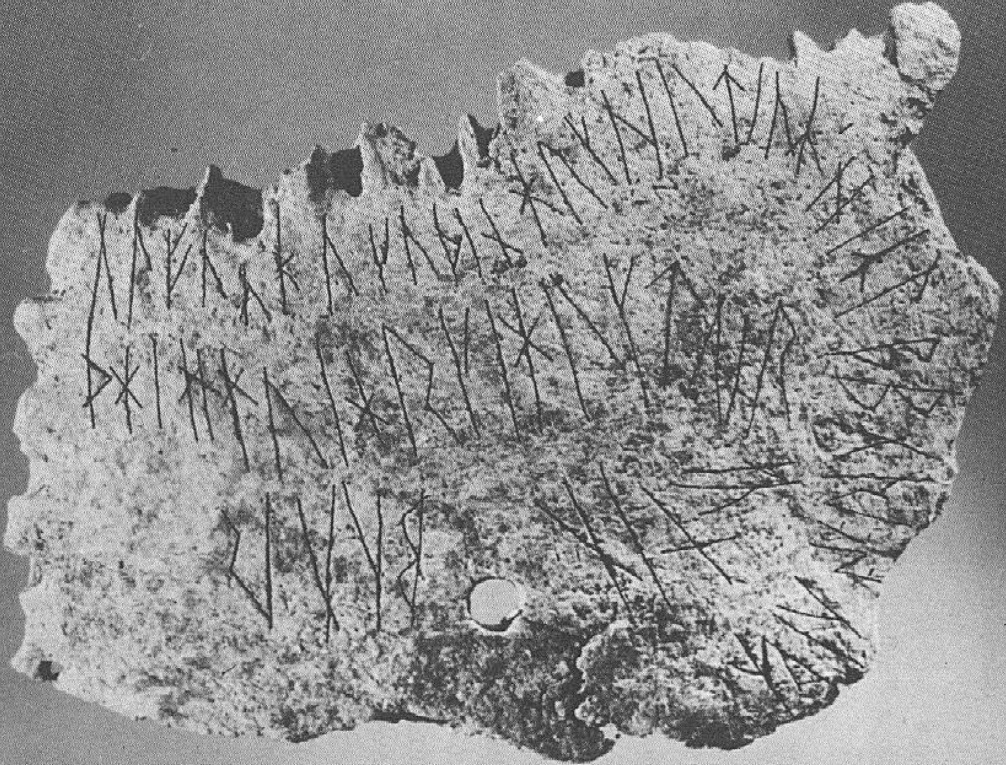

In parallel, the use of artifacts with a "spiritual" nature—a concept that would align more closely with the term of seiðr, a practice used by the Norse people for divination, healing, and supernatural warfare (Leduc, 2015)—were also inventoried. These included the human skull fragment from Ribe or the Sigtuna copper plate. These objects were probably used in combination with medicinal plants. However, it appears that plants could have primarily been used to treat physical injuries, whereas the seiðr was more commonly employed to address illnesses or bodily reactions.

Finally, during my research master, I was able to identify the main challenges the Norse people faced. The analysis of their living environment and activities shaping their bodies allowed us to build a vision of their harsh daily lives to understand what they had to fight against, and the benefits they gained from it, such as a good immune system. Their health appears to have depended on a fairly varied diet, although this varied from location to location, with differences between urban and rural settlements, coastal and inland regions, and between broad geographic zones.

What’s next?

The topic of Viking healthcare is very broad. As I was unable to address all the relevant data in my master’s thesis, it should be considered as an introduction to the subject, which I will now continue in the context of my PhD research here at Leiden. Archaeology, will be my main data source, and I will be inventorying as many scattered materials as possible from museums and excavation reports. In addition, as the Viking expeditions extended their connections eastward, reaching as far as Constantinople and Baghdad (Boyer, 2004), I will explore in depth the possible medical influence and connections with the Islamic and Byzantine worlds.

As additional annual posts are considered to update this research, I invite interested individuals to stay tuned here for more information in the future.

References :

- Bauduin, P. (2018). Les Vikings (3rd edition). Que sais-je ?

- Blindheim, M. E., Boyer, R., Chabot, G., Musset, L., Périn, N., & Quenardel, J.-M. (n.d.). Scandinavie [Encyclopædia]. Retrieved 20 February 2022, from http://www.universalis-edu.com...

- Boyer, R. (2004). Les Vikings: Histoire et civilisation. Perrin.

- Leduc, C. (2015). Le seidr des anciens Scandinaves et le noaidevuohta des Sâmes: Aspects chamaniques et influences mutuelles [University of Ottawa]. http://hdl.handle.net/10393/32...

- Moltke, E. (1985). Runes and Their Origin: Denmark and Elsewhere. National Museum of Denmark.

- Thráinn Thórðarson, B., Erlandson, J. M., Holck, P., Eng, J. queline T., Grimes, V., Fuller, B. T., Guiry, E. J., Cecilie Juel Hansen, S., Hrei ðarsd óttir, E., Milek, K., Connors, C., Baier, W., Baker, K., Wake, T., Leifsson, R., Erlendsson, E., Edwards, K. J., Gíslad óttir, G., Martin, S. L., … Kalmring, S. (2014). Viking Archaeology in Iceland: Mosfell Archaeological Project (D. Zori & J. Byock, Eds.; Vol. 20). Brepols Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.CURS...

© Simon van der Straten and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Simon van der Straten and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.