Pigs and Bagpipes: Geoffrey Chaucer's Miller in Context

Geoffrey Chaucer drew on various medieval traditions surrounding pigs to characterise one of his most memorable characters in the Canterbury Tales: Robin the Miller

A boarish fellow

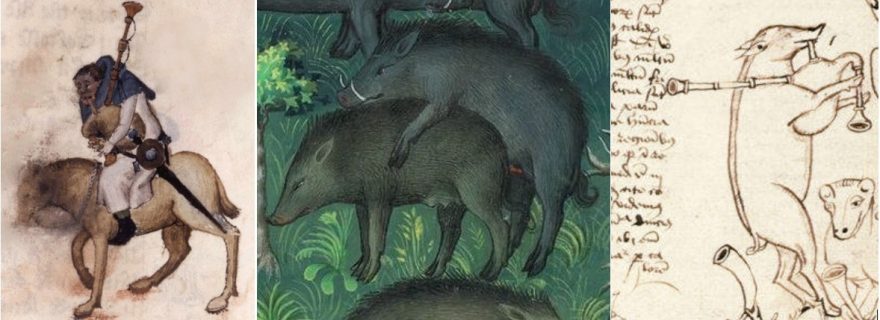

In his Canterbury Tales (1387-1400), Geoffrey Chaucer brings to life a great variety of characters who set out on a pilgrimage to Canterbury. To pass the time, the pilgrims tell each other stories and, along the way, the audience learns about the pilgrims' appearance, their behaviour and how they react to each other's tales. Perhaps one of Chaucer’s most memorable characters is Robin the Miller, depicted here in the early-fifteenth-century Ellesmere manuscript:

Robin the Miller in the Ellesmere Manuscript (Huntington Library, EL 26 C 9; source)

Chaucer’s Miller behaves like a pig and his demeanour towards his fellow pilgrims is nothing short of boarish: he drunkenly interrupts the Knight and the Host and angers the Reeve by telling a bawdy tale about how a carpenter was tricked by a student (the Reeve used to be a carpenter). The Miller’s interests are also ungentlemanlike: Chaucer reveals in his General Prologue that Robin the Miller is “a janglere and a goliardeys, And that was moost of synne and harlotries” [a buffoon and teller of dirty stories, mostly about sin and deeds of harlotry] (General Prologue, ll. 560-561). Indeed, the Miller’s Tale is all about sex and obscenities. One of the Tale’s highlights is the moment a parish clerk accidentally kisses a woman’s arse (incidentally, the woman’s response, “Tehee!”, is the first recorded instance of the interjection “Teehee!” in the English language). The clerk, disgusted and out for revenge, pretends to return for another kiss and, after being farted in the face, shoves a redhot poker up the offending orifice. Robin the Miller certainly has a wicked sense of humour and a mind like a sow: full of dirty thoughts.

A sow in body and mind

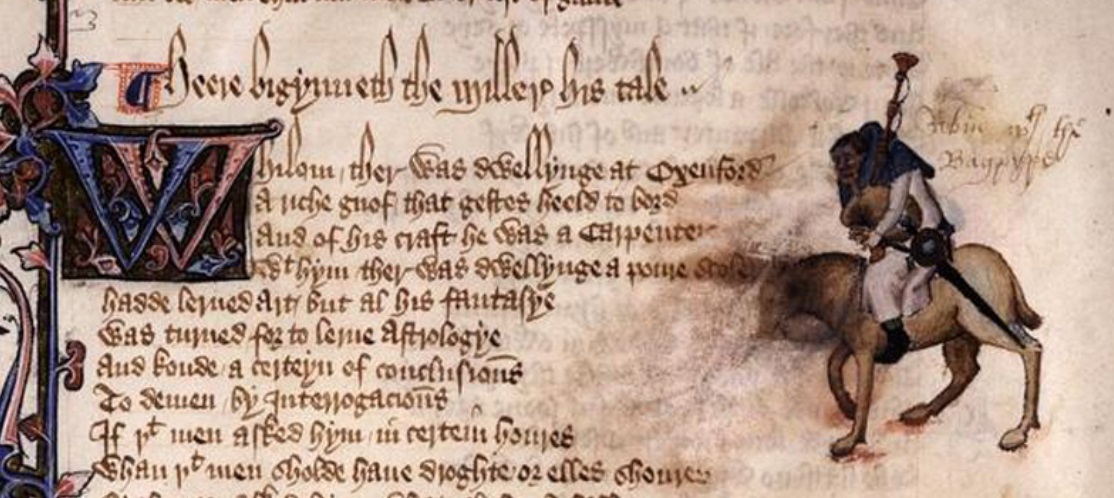

Copulating boars in Le livre de chasse (1407; source) and a sow in London, British Library, Harley 4751, fol 20r (England, 13th century).

‘A mind like a sow’? Let me explain by first pointing out that the Miller, in his appearance, also resembles a female pig. The Miller is a stout fellow, full of brawn, who likes wrestling and has a big mouth; more importantly, the Miller’s red hair is explicitly linked to the sow:

His berd as any sowe or fox was reed,

And therto brood, as though it were a spade.

Upon the cop right of his nose he hade

A werte, and theron stood a toft of herys,

Reed as the brustles of a sowes erys (General Prologue, ll. 552-556)

[His beard was as red as any sow or fox, and also broad, as if it were a spade. On the top of his nose he had a wart, and thereupon stood a tuft of hairs, as red as the bristles of a sow’s ears.]

These two references to the sow are no coincidence. In the Canterbury Tales, animal imagery is often used to highlight certain aspects a character shares with these animals. The female pig is a good ‘spirit animal’ for the Miller since, according to medieval bestiaries, the sow represents dirty-minded, unclean people. The entry for ‘sow’ in Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley 764, for instance, explains:

The pig (porcus) is a filthy beast (spurcus): it sucks up filth, wallows in mud, and smears itself with slime. ...Sows signify sinners, the unclean and heretics ... Sows are unclean and gluttonous men ... The pig is also the man who is unclean of spirit. ... The sow thinks on carnal things; from her thoughts wicked or wasteful deeds result ... (trans. Barber 1992, pp. 85-87)

Clearly, Chaucer’s red-haired Miller, rejoicing in sin and telling dirty stories, is like a sow in both body and mind.

A porky piper

One more intriguing detail links Chaucer’s Miller to a sow: “A baggepipe wel koude he blowe and sowne, / And therwithal he broghte us out of towne” [he well knew how to blow and play the bagpipes and with that he brought us out of the town] (General Prologue, ll. 565-566). Chaucer’s Miller shares his ability to play the bagpipes with various pigs that make their appearance in late medieval art. Porky pipers may be found on wooden misericords...

15th-century misericords in Ripon cathedral and Manchester cathedral (photos by author)

... hanging from the roof of Melrose Abbey ...

Pig playing bagpipes on the roof of Melrose Abbey (15th century?)

... pilgrim badges ...

Pilgrim badge (1375-1450) of a boar playing the bagpipes (clearly not a sow!). (source)

... and in medieval manuscripts:

Doodles in London, British Library, Sloane 748, fol. 82v (England, 1487)

Exactly what connects the bagpipes to the sow is uncertain: the form of the instrument (a bag with a pipe) might be interpreted as phallic in nature and the bagpipe, like the sow, was associated with sexual sin in the Middle Ages; it was an “impious instrument with sexual connotations” (see Planer 1988, 343). Alternatively, there may be a link between the sound of a screaming pig and the bagpipes (both unpleasant sounds?). Whatever the connection between pigs and bagpipes, we may assume that Chaucer and his audience were familiar with this artistic tradition since most depictions of these porky pipers stem from fourteenth- and fifteen-century England. What better instrument for the boarish Miller, with the body and mind of a sow, than the bagpipes?

Chaucer’s Miller truly is a pig, in more ways than one.

References:

- Planer, John H. 1988. "Damned Music: The Symbolism of the Bagpipes in the Art of Hieronymus Bosch and His Followers." In Music from the Middle Ages Through the Twentieth Century: Essays in Honor of Gwynn S. McPeek, ed. C.P. Comberiati & M.C. Steel (New York), 335-356.

- Barber, Richard. 1992. Bestiary: Being an English Version of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS Bodley 764 (Woodbridge)

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.