Following French Fashion: The Dutch Book of Hours in Print

On 16 August 1491, the most prolific printer of the Low Countries at the time, Gerard Leeu (d. 1492) published his only edition of a Book of Hours in Dutch. The book itself, however, looks French. Why was Leeu swayed by French fashion?

Medieval Bestseller

The Book of Hours was without a doubt one of the bestsellers of the Middle Ages. The book gave many readers the possibility to participate in the prayer practices and the cyclic rhythm of monastic prayer throughout the day. While often associated with richly decorated and illuminated manuscripts made for the delicate hands of kings and queens, most Books of Hours, however, were executed as relatively simple (paper) manuscripts. Especially in the course of the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries, the Book of Hours came within the reach of a growing group of readers. Changes did not only occur in the materiality of the Book of Hours. At the end of the fourteenth century, the Book of Hours was translated into Dutch by Geert Grote, the initiator of the religious reform movement that would have a large impact on religious and devotional life in the late medieval Low Countries – the Devotio Moderna (or: Modern Devotion). Earlier translations did exist, but the popularity of Grote’s translation – based on the numbers of surviving manuscripts (more than 800) – reached a lonely peak.

So what happened to the Dutch Book of Hours (and its popularity) after the introduction of the printing press in the Low Countries in 1473? And how does Leeu’s edition from 1491 fit into this transition from manuscript to print?

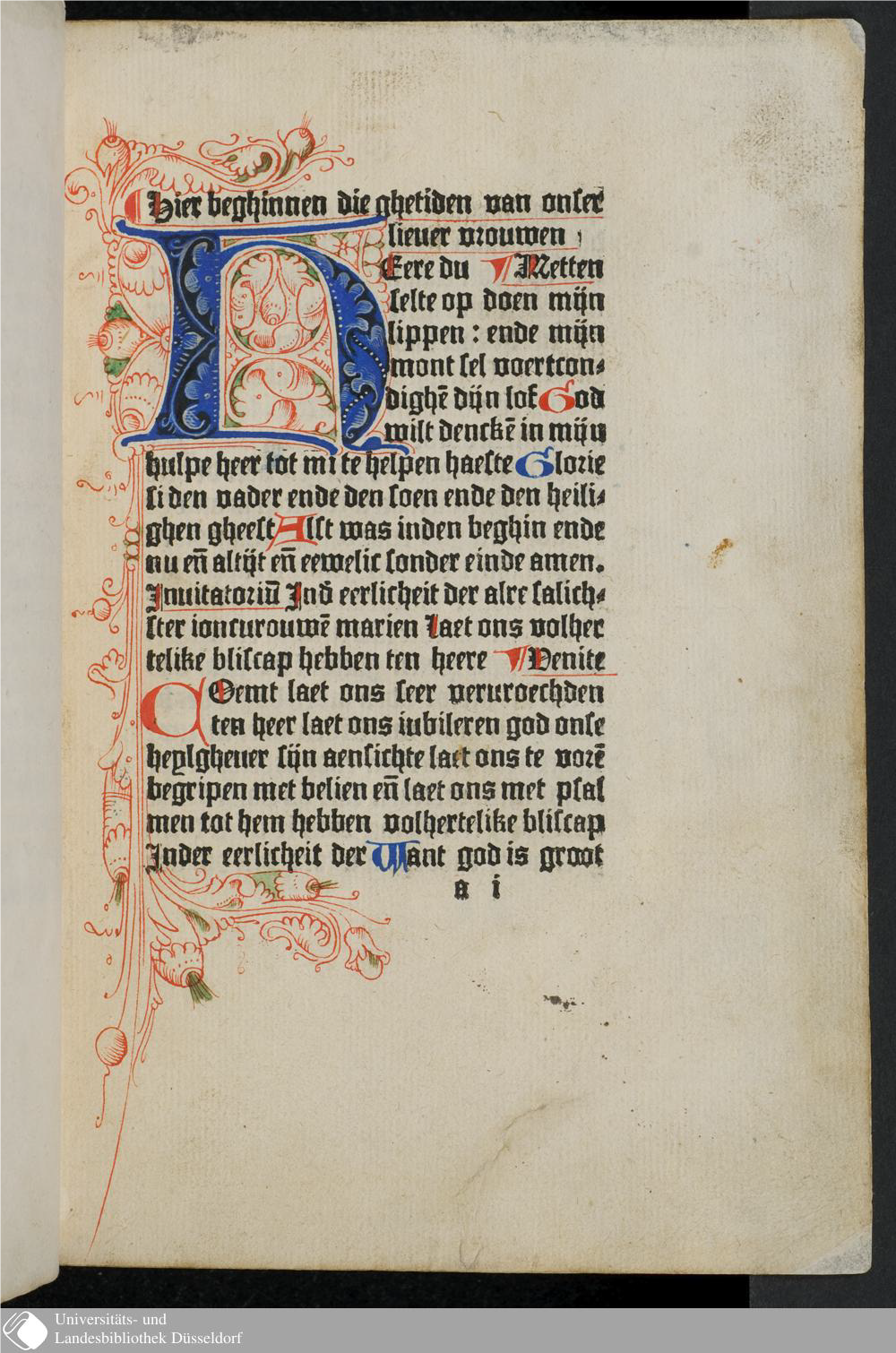

Ill. 1. Start of the Hours of Our Lady. Delft : [Jacob Jacobszoon van der Meer], 8 Apr. 1480. 4°, fol. a1r. Copy: Düsseldorf : Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, cat. 452, urn:nbn:de:hbz:061:1-112384.

Prayer in Print

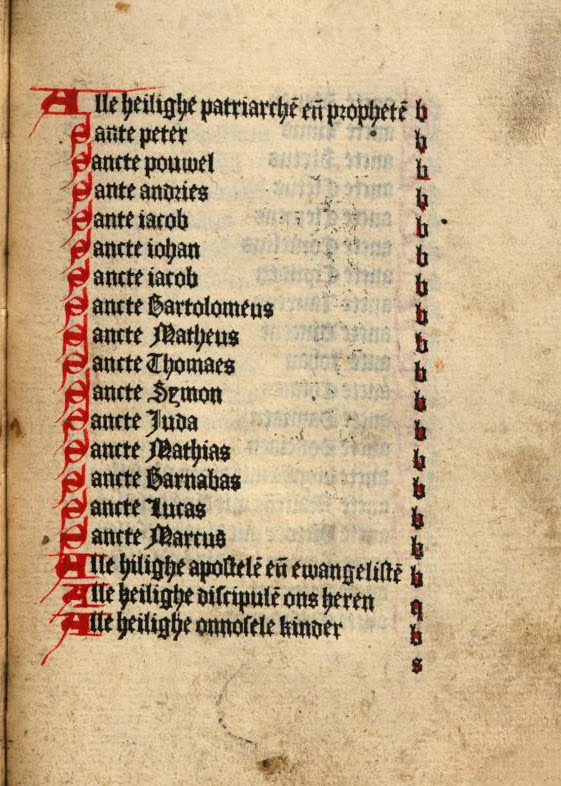

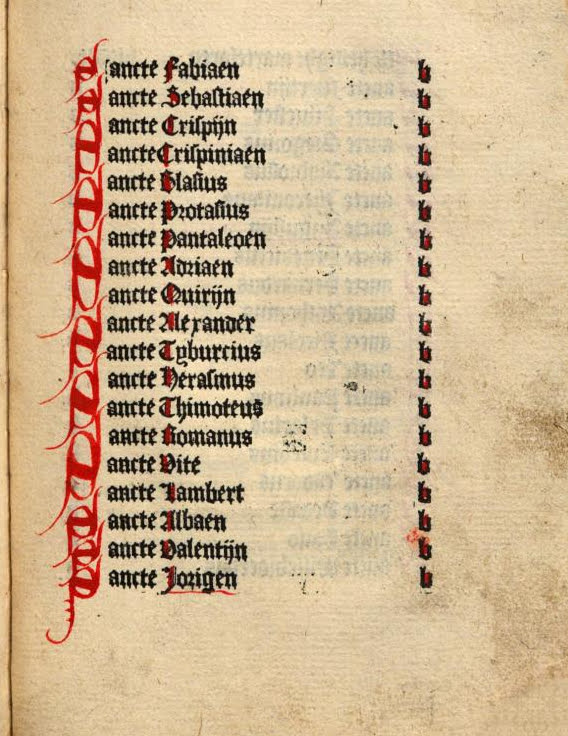

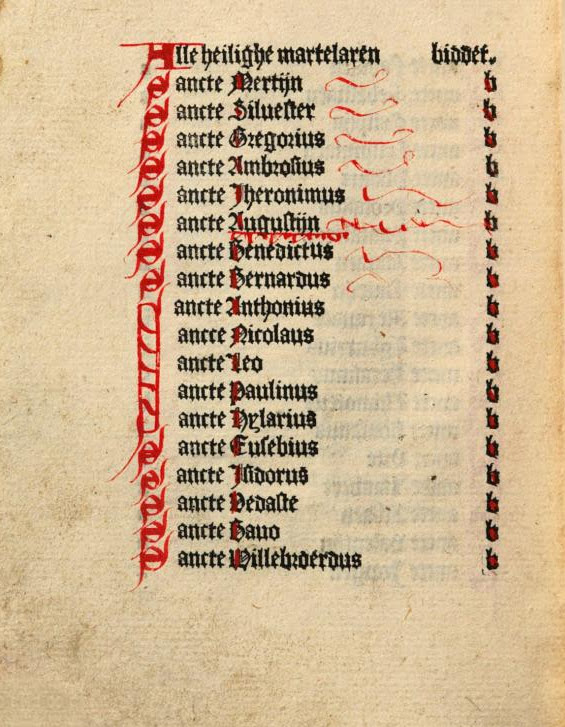

The production of Dutch Books of Hours started in Delft in 1480, and was soon followed by editions executed by printers in Brussels and Hasselt in the 1480s. These books are not illustrated, and especially the Delft editions imitate manuscripts. These printed books, similar to – and in imitation of – manuscript production, were only half finished when they came off the press. They needed to be completed by hand: decorated initials were added, in this case locally in Delft, which gave the impression of a handwritten book (ill. 1). The Books of Hours printed in Hasselt were also finished by hand through the addition of simple initials and rubrication. In one of the copies the boredom that set in during this kind of work seeps from the pages with the Litany of the Saints, where each line needed a small initial ‘S’. At first the rubricator dutifully fulfilled his task, but along the way we can literally see him thinking: ‘how can I get this chore over with as soon as possible?’ The further one leafs, the bigger the S’s get, and the rubircator even invents a multiple-S’s-in-one technique (ill. 2).

Ill. 2. Litany of the Saints. Hasselt : [Peregrinus Barmentlo], 1488. 8°, fols. s1r, s2r, and s2v. Copy: The Hague, National Library of the Netherlands, 150 F 8, Google Books: https://books.google.nl/books?vid=KBNL:KBNLB030063601&redir_esc=y

Print and Parisian Fashion

Leeu’s edition of the Duytsche ghetiden [The Dutch Hours] produced in 1491 is the first fully illustrated printed Book of Hours in the Dutch language – in 1490/91 Christaen Snellaert produced a Book of Hours in Dutch with a small number of images, which were copied from an earlier edition published by Leeu in Latin (Kok 2013) (ill. 3). The 1491 edition seems to constitute a break with manuscript tradition. The impact of the printing press, however, did not so much affect the text, but rather the appearance of the book. The printed book reproduces the translation of the Hours (supplemented with prayers) made by Geert Grote more than a century ago and transmitted in unparalleled quantities of manuscripts. Leeu does not reprint the text from an earlier edition, however, but uses his own (possibly Bridgettine) manuscript source – his edition contains a different constellation of texts from the earlier printed Books of Hours. Where Leeu wanders off the traditional manuscript path, is the decoration and illustration. The book looks decidedly different from manuscript Books of Hours produced in the Low Countries, for example in Ghent and Bruges where we find so-called ‘strewn borders’. Moreover, the woodcuts deviate relatively strongly – in style and in finish – from all the other woodcuts Leeu used.

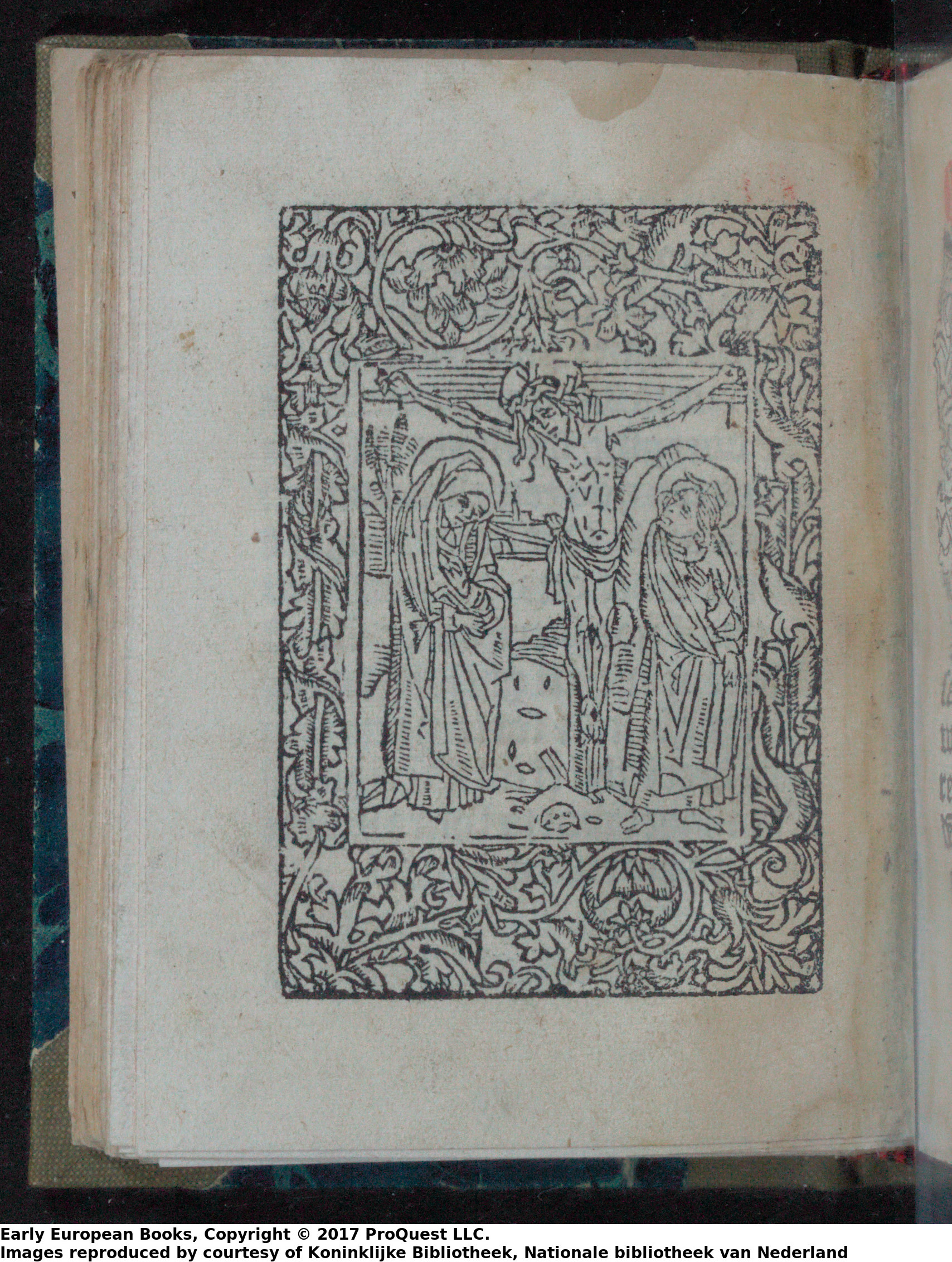

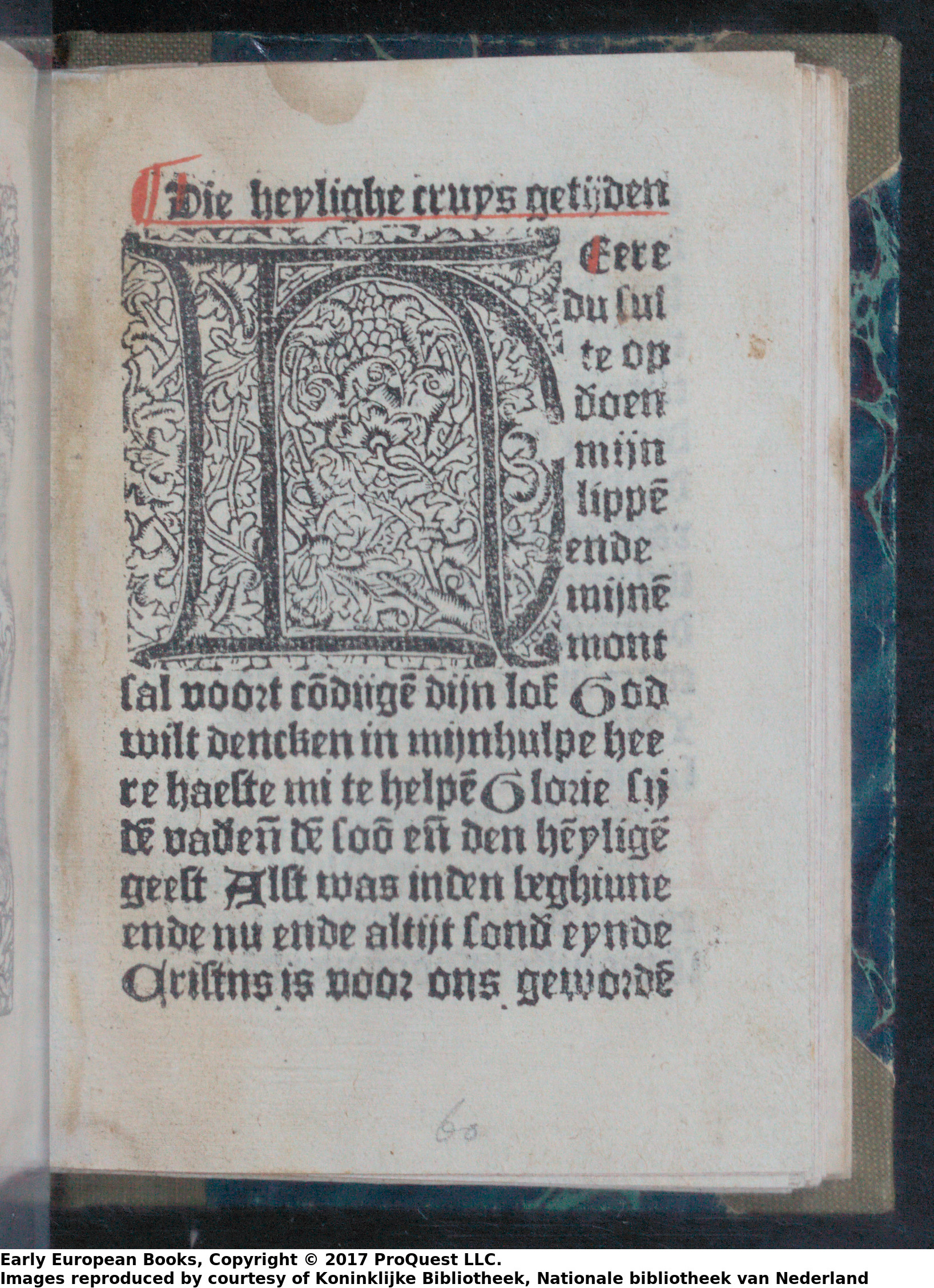

Ill. 3. Start of the Short Hours of the Holy Cross. Delft : [Christiaen Snellaert, [between 29 May 1490 and 10 Aug. 1491]. 8°, fols. f3v-f4r. Copy: The Hague, National Library of the Netherlands, 150 E 26. Early European Books, ProQuest LLC.

Leeu’s Book of Hours looks unquestionably French. On all pages finely cut woodcut borders surround the text, and a large woodcut marks the start of each text. When it came to printing an illustrated Book of Hours in Dutch, Leeu did not look to the traditional Netherlandish forms of decoration. He looked towards the French production of printed Books of Hours that had started relatively recently, in the late 1480s. Leeu seems to follow international trends and innovations in printed book production here, and this international influence appears to cause a clear break between manuscript transmission and printed books in terms of lay out and decoration. The French connection has already been noted by a number of scholars (Kok 2013 and Petev 2013), and more research is needed to uncover the exact relationship with Parisian production of Books of Hours.

With his 1491 edition Leeu started a tradition of Dutch Books of Hours in French style in Antwerp: printers such as Adriaen van Liesvelt continue to work in ‘Leeu’s tradition’ (ill. 4). Around 1500 Parisian printers themselves start producing Books of Hours in Dutch. The reason Leeu swayed for French fashion looks to be – perhaps not surprisingly – mainly commercial: it allowed him to produce a ready-to-use and moreover attractive Book of Hours. His edition shows an awareness of new innovations in printed book production, an international orientation, and an eye for commercial opportunities. In the case of the Book of Hours, Leeu seems to have had a great foresight: it is almost as if he anticipated that the production of Books of Hours in Dutch would move south.

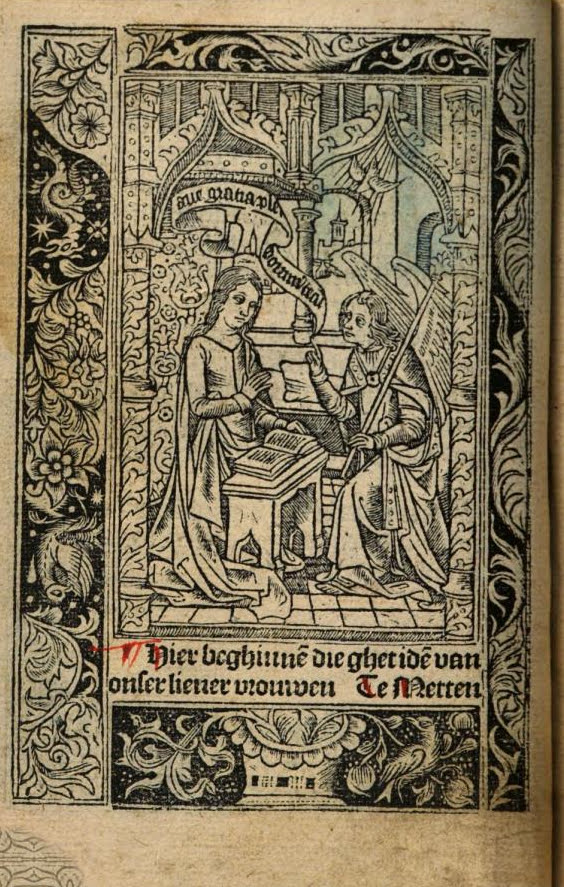

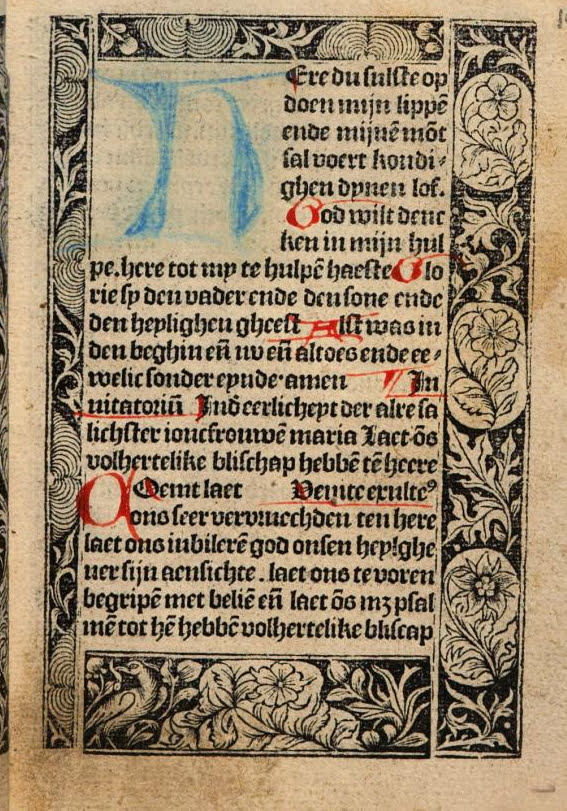

Ill. 4. Start of the Hours of Our Lady. Antwerp : Adriaen van Liesvelt, 29 July 1495. 8°, fols. 13-14. Copy: The Hague, National Library of the Netherlands, 150 F 33, Google Books: https://books.google.nl/books?vid=KBNL:KBNLB030063603&redir_esc=y

Further reading

Ina Kok, Woodcuts in Incunabula Printed in the Low Countries. 4 vols. Houten: Hes & De Graaf, 2013.

Todor Petev, ‘A Group of Hybrid Books of Hours’. In: Books of Hours Reconsidered, eds. S. Hindman and J. Marrow. London: Harvey Miller Publishers, [2013], 391-408.

Virginia Reinburg, French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c.1400–1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139030496