Curious drawings in a medieval account book, part 1: A tiny hand

In one of the account books kept in the National Archives in The Hague, a tiny hand is drawn. What is its significance?

The starting point of this blog is a small, dog-eared document, kept in the Dutch National Archives in The Hague. It concerns an account covering the years 1357-1358, compiled by a certain Heynric van Dronghelen, bailiff (drost) of the Land of Heusden, a territory situated in the border region of Brabant, Guelders and Holland. Little is known about Heynric, but we may assume that he was a relative – perhaps a son or a nephew – of Jan van Dronghelen, Lord of nearby Eethen and Meeuwen, who served as a prominent counsellor to the Count of Holland.

The account provides interesting information about the challenging siege of Heusden Castle in 1357. It was in the hands of a rebellious nobleman and subsequently besieged by Heynric in the name of the Count of Holland. The account records various expenditures, such as 62 pounds for the construction of a blockhouse, 97 pounds for a floating platform on the river Maas, 100 pounds for a canon (donrebus) and powder, and 75 pounds for 30 men who were billeted in the blockhouse for a period of 15 days. However, rather than focussing on military and financial issues, this blog explores theme of administrative accountability.

At first glance, Heynric’s account is not exceptional. It is just one of the many financial and administrative records that have been handed down in the count's archives. These documents were used to determine the servant's debt or credit in relation to his master. The account details Heynric’s income and expenses as bailiff and was audited by members of the Count’s inner council. The audit was conducted on 11 November 1359 and was carried out by four high-ranking noblemen and a clerk. Even the fact that the account shows a huge deficit – the income amounts to 2500 pounds, the expenses to 4600 pound – is not exceptional either. However, there is one thing that sets it apart: the drawing of a tiny hand in the margin of folio 28.

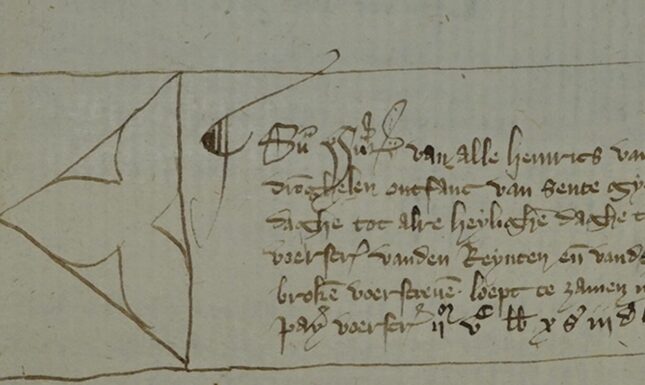

Illustration 1 shows the summa summarum, the grand total written on the last page of Heynric’s account and reveals the handwriting of two scribes. The first hand, probably belonging to Heynric himself, wrote in light brown ink the total amount that he had spent. He then drew a box around it. Underneath the text box, a tiny hand can be seen pointing at the box and the text it contains. Another scribe, probably Dirc Voppenzoon, the attending clerk at the audit, then wrote a text in darker brown ink to note the total amount of the income, the names of the people auditing and the date the audit took place. While writing, the clerk crossed the bottom line of the box drawn previously. It was not uncommon to draw a frame around the summa summarum of an account, in order to highlight the essence of the document. A comparable one can be found a few folios earlier, where it contains the total amount of the income (illustration 2) and in several other accounts. However, this does not apply to the tiny hand that is shown here. What is its meaning?

Calling attention from the margins of manuscripts: Maniculae

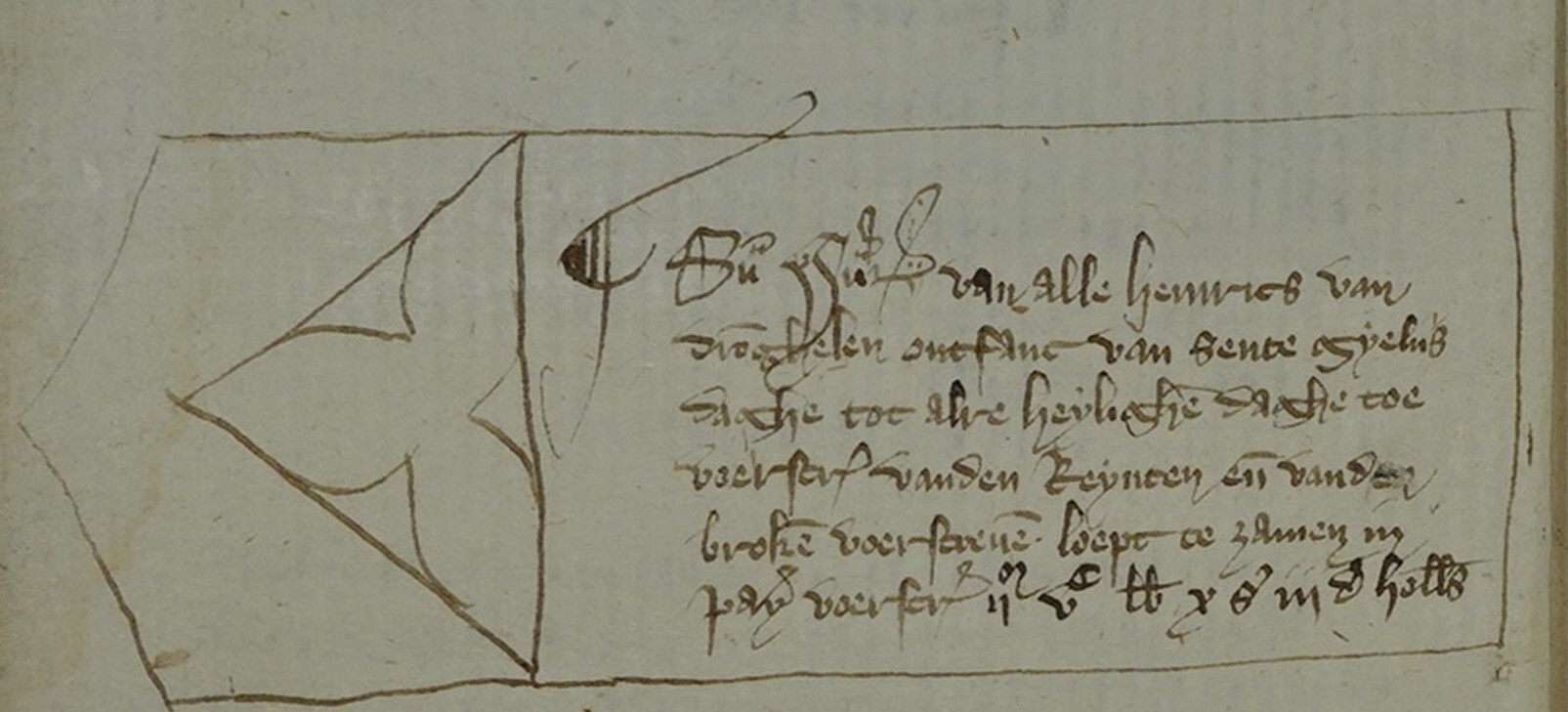

Tiny ‘hands' are far from uncommon in the Middle Ages; they can be found in the margins of many manuscripts from the twelfth century onwards. Readers added these so-called maniculae (manicules, literally ‘little hands’) to the margins of a text when they were struck by a particular passage or wanted to direct a later reader’s attention to it. These marks are not part of the original layout of the manuscript; they are signs of use. Typically, only the index finger of the manicula is stretched out, sometimes to enormous proportions. Illustration 3 shows a random example in a manuscript dating from the thirteenth century.

A closer inspection reveals that the hand in Heynric’s account is, in fact, not a manicula. Contrary to the maniculae, it was not drawn by a reader, but by the scribe of the account himself when compiling the sum of the expenses. More important though, is the fact that the typology is different. As we can see from the nails, Heynric’s drawing shows a right hand, with two outstretched fingers, the index and middle finger, pointing upwards to the text box. Below these two fingers, we can see what is probably the top and the nail of the thumb, followed by the curved ring finger and little finger. A comparable gesture is often seen in images with a religious character, referring to a blessing. Closely related, this gesture is commonly used on images in manuscripts with legal or administrative character, and sometimes on paintings. There the hand does not, or at least not primarily, point at a passage of text, but at a reliquary, at a crucifix, at the Holy Scripture or at heaven. A raised right hand, with two, sometimes three fingers stretched was used when a person took an oath, for instance when he promised loyalty when he was appointed to an office, or when he testified in a judicial case.

Oath-taking gestures in the later Middle Ages

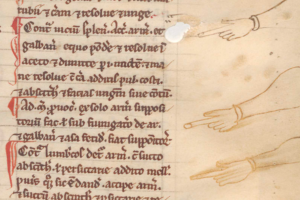

We can clearly see a gesture similar to the one in Heynric’s account in the miniature included in the inventory that Secretary Adriaan van der Ee made in 1438 for the duke’s chancellery of Brabant (illustration 4). Three aspiring vassals swear an oath of fealty to the Duke of Brabant, with their right hand raised and pointing their index and middle finger upwards.

The Heidelberg exemplar of the famous Sachsenspiegel, a record of local customary laws dating from the first decades of the fourteenth century provide another clear example (illustration 5). Here, a witness is shown, swearing an oath in front of a judge and aided by three compurgators (oath-helpers). All four use both the index and middle finger of their right hands, now not pointing at heaven, but at what appears to be a reliquary.

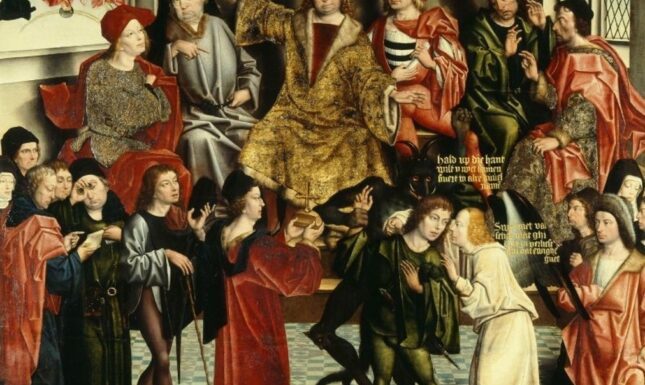

Derick Baegert’s painting of the Eidesleistung (oath-taking in court) is another example (illustration 6). The city council of the town of Wesel (Lower Rhine region) commissioned it in 1493-1494. The painting depicts a scene where one of the litigants, or a witness, is ready to swear an oath on the crucifix that a court official holds out to him (the figure is in the foreground, clad in dark green). He has already raised his right hand, with the index and the middle finger extended upward, but he is still undecided whether to follow the advice of the white angel or the black devil who is holding his wrist. We remain uncertain about the outcome.

Oaths were vital in pre-modern society. Since time immemorial, people have sworn oaths to affirm their credibility. Written evidence was limited and control mechanisms often lacking; administration, jurisdiction and finances therefore had to rely heavily on trust, personal contact and the word of interested parties. An oath is ‘a solemn speech act performed according to some established formal procedure’. Oath-taking had a public or semi-public character, and in nearly all cases a deity was invoked as a witness whose punishment is called down if the promise were broken (Esders 2023). In other words: when swearing an oath, you put your eternal damnation at risk. In German, this is referred to as Selbstverfluchung – self-curse. With a promissory oath – like in the miniature of the vassals swearing fealty to the Duke of Brabant – one could affirm their future loyalty to rulers or superiors. An assertive oath confirmed an existing right or observation made in the past.

Conclusion

Let us return to the account drawn up by Heynric van Dronghelen as bailiff of the Land of Heusden. He was responsible for the administration of finances during the war in his territory. How could anyone auditing know if he hadn’t cheated? The auditors must have been rather convinced that he had handed in an honest account, and by closing it on 11 November 1357 they approved it. But still, how could they be sure? Heynric could have billeted 25 soldiers in the Blochouse near Heusden, instead of 30, and he could have pocketed the 12.5 pounds difference. The construction of a blockhouse could have cost 60 pounds instead of the 62 Heynric declared, the floating platform 90 pounds instead of 97. Only Heynric and God really knew. By taking an affirmative oath on his account, Heynric took God as his witness that it contained the truth, and nothing but the truth.

The evidence – a marginal sketch of a tiny hand with two raised fingers – may seem a bit insubstantial. In the following blog, other illustrations in the accounts will be discussed that lend support to this interpretation.

Suggested reading:

- Karl von Amira, Die Handgebärden in den Bilderhandschriften des Sachsenspiegels (München 1909).

- Jaume Aurell, Montserrat Herrero, ‘Introduction. The Oath: The Word and the Sacred’, in Jaume Aurell, Montserrat Herrero (eds.), Le sacré et la parole (Rencontres 378) (Paris 2018) 7-14.

- Anne-Maria van Egmond, Materiële representatie opgetekend aan het Haagse hof, 1345-1425 (Hilversum 2020).

- Stefan Esders, ‘Loyalty Oaths and the Transformation of Political Legitimacy in the Medieval West’, in: P. Buc, T.D. Conlan (eds.), Oaths in Premodern Japan and Premodern Europe (Medieval Worlds 19) (Vienna 2023) 119-140.

- Kathryn M. Rudy, Touching Parchment: How Medieval Users Rubbed, Handled, and Kissed Their Manuscripts Volume 1: Officials and Their Books (Cambridge UK, Open Book Publishers, 2023). https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0...

© Robert Stein and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Robert Stein and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.