Automated Reading of Medieval Manuscripts: An Alternative for Palaeography Classes?

New technologies may well blow the ‘dust’ off traditional scholarly skills such as palaeography, which risk being scratched from curriculums. In the ‘Digital Editing’ class in Leiden University’s Dutch department, students helped train a computer to automatically read medieval manuscripts.

Declining skills?

To humble scholars working with medieval manuscripts today, the amount of work done by their nineteenth-century predecessors is often baffling. They were versatile scholars who were just at home in modestly lit study rooms corresponding internationally about their editorial work, as they were in ragged coaches travelling the bumpy roads of Europe, in search of undiscovered manuscripts and new medieval texts. Some 150 years later, scholarship often still relies on the text editions and catalogues that these scholars made, pioneering not only in discovering new manuscript material, but also in setting the standards of scholarly editing. The value of their work is grounded not in theoretical approaches, but in the actual fieldwork of philology: tracing manuscripts, studying and comparing them (codicology, philology), and deciphering the text that was written down centuries ago (palaeography).

In recent decades, scholarship on medieval literature has turned increasingly towards the manuscripts in which texts have been preserved and the contexts in which they circulated. This has led to the insight that nineteenth-century editions often did little justice to the variety between different versions of the same text, and the extent to which this variety testifies to the context in which manuscripts were made and read. A renewed focus on manuscript material has again underlined the value of basic ‘practical’ scholarly skills such as palaeography and codicology. But while these are becoming more important in scholarly research, their presence in the curriculums of future students is a subject of debate. Only very recently, a colleague at the Leiden History department, Robert Stein, indicated the overall decline of palaeography and other ‘auxiliary sciences’.

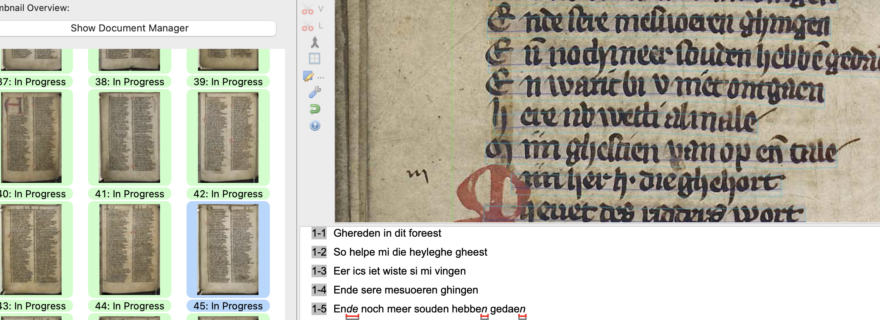

Efforts are being undertaken to turn the tide – see for example the attractive training website ‘Watstaatdaer’ (see fig. 1), which has organised a yearly palaeography competition since 2020. But while the situation is different for students of various disciplines (literary history, art history, history, archaeology…), it is fair to say that a thorough training in palaeography is not as evident as it once was. At the same time, access to manuscript material, be it archival records or medieval manuscripts, has never been easier. In the past decade, institutions worldwide have been digitising and making their collections available online at an increasing pace (see, for example, this recent blogpost on Leiden University Library’s digitisation efforts), and if the Covid pandemic has brought some good, it is that it has been a great catalyst for digitisation efforts.

Automated help

But online access to digitised images is still a far stretch from having machine-readable information that can easily be used for research purposes. It is this divide between the ever-growing quantity of digital images of handwritten source material on the one hand, and the decreasing skills and availability of people that can process these images on the other, that has pushed researchers towards developing new technologies for ‘Handwritten Text Recognition’ or HTR.

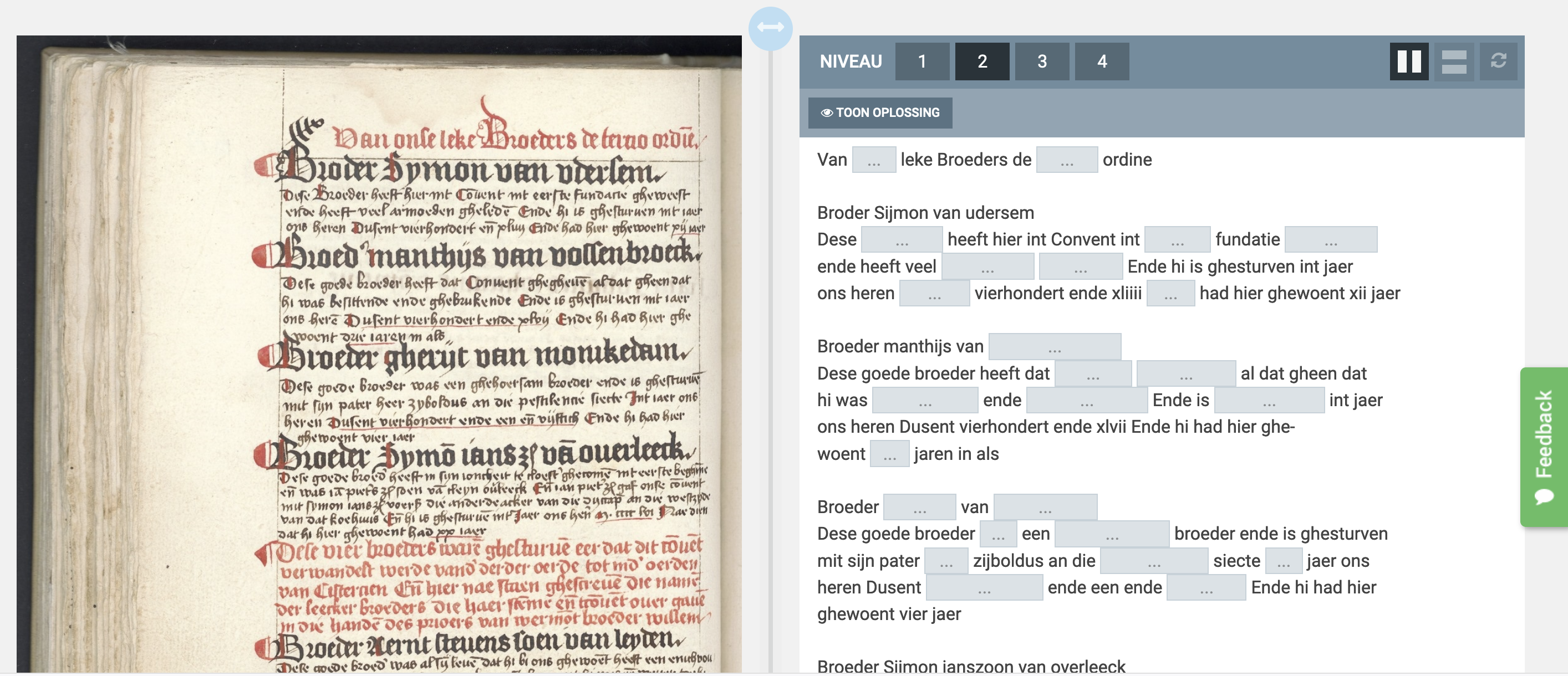

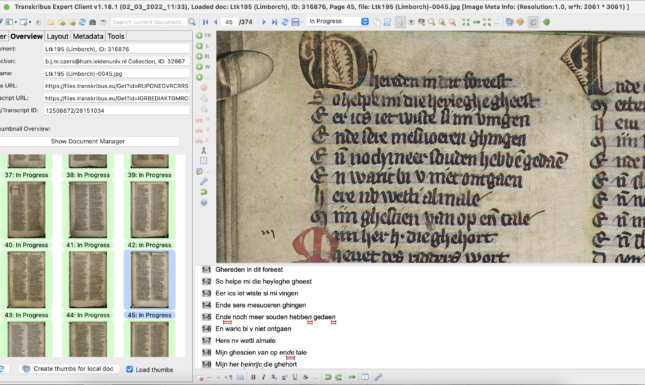

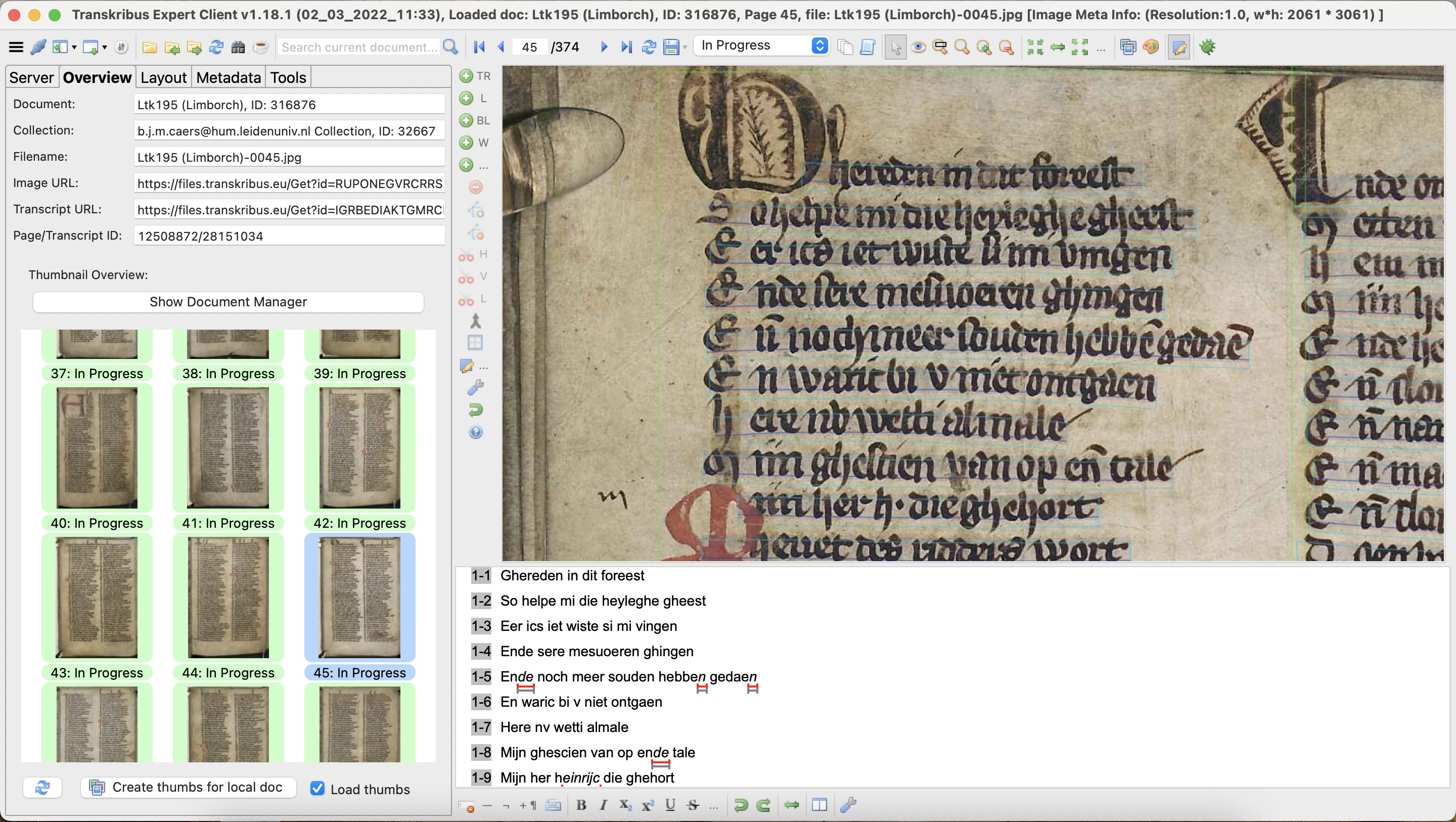

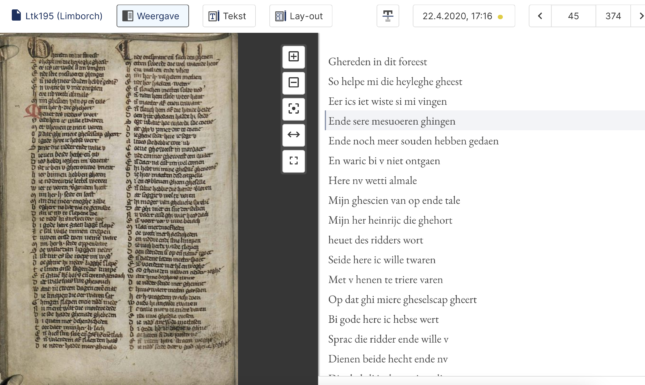

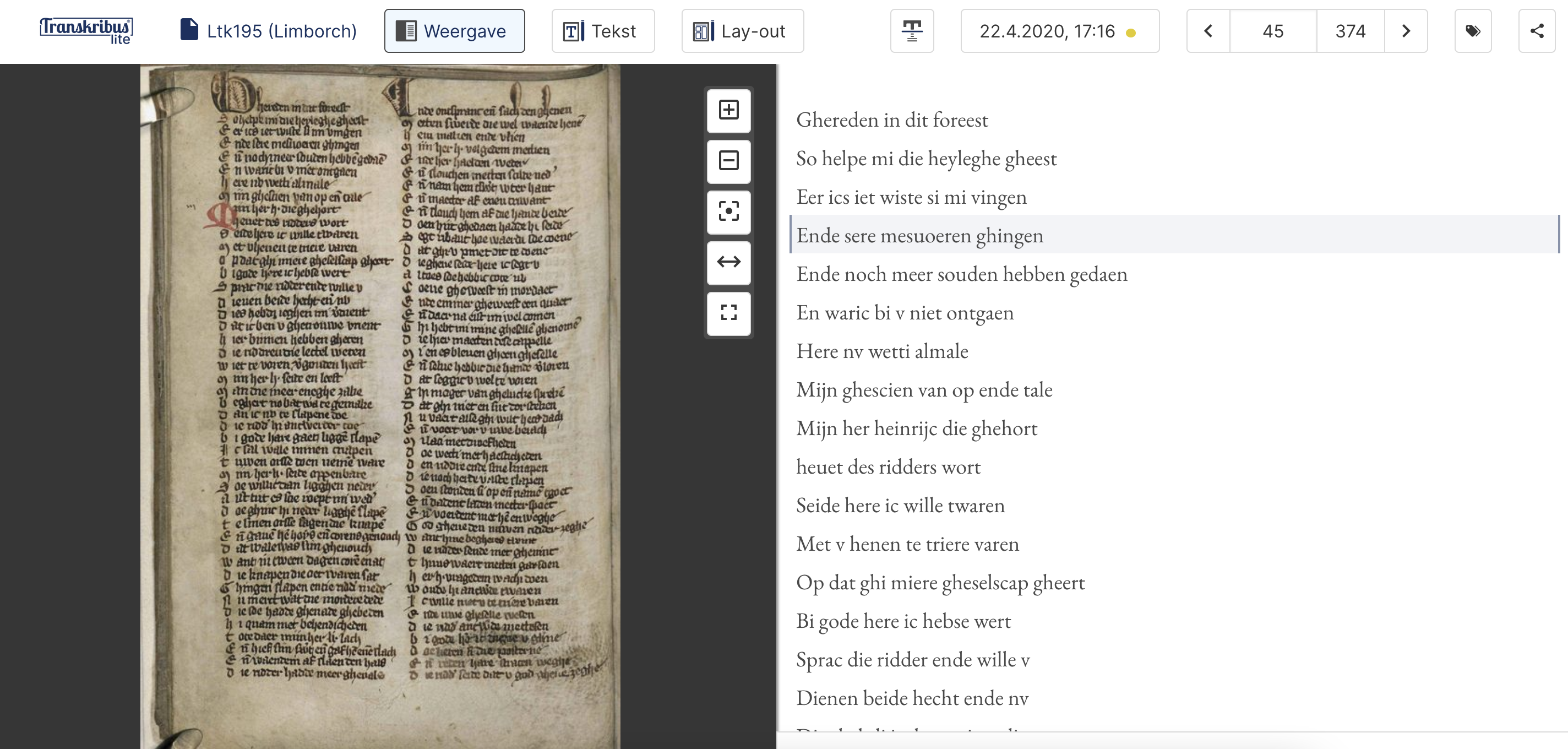

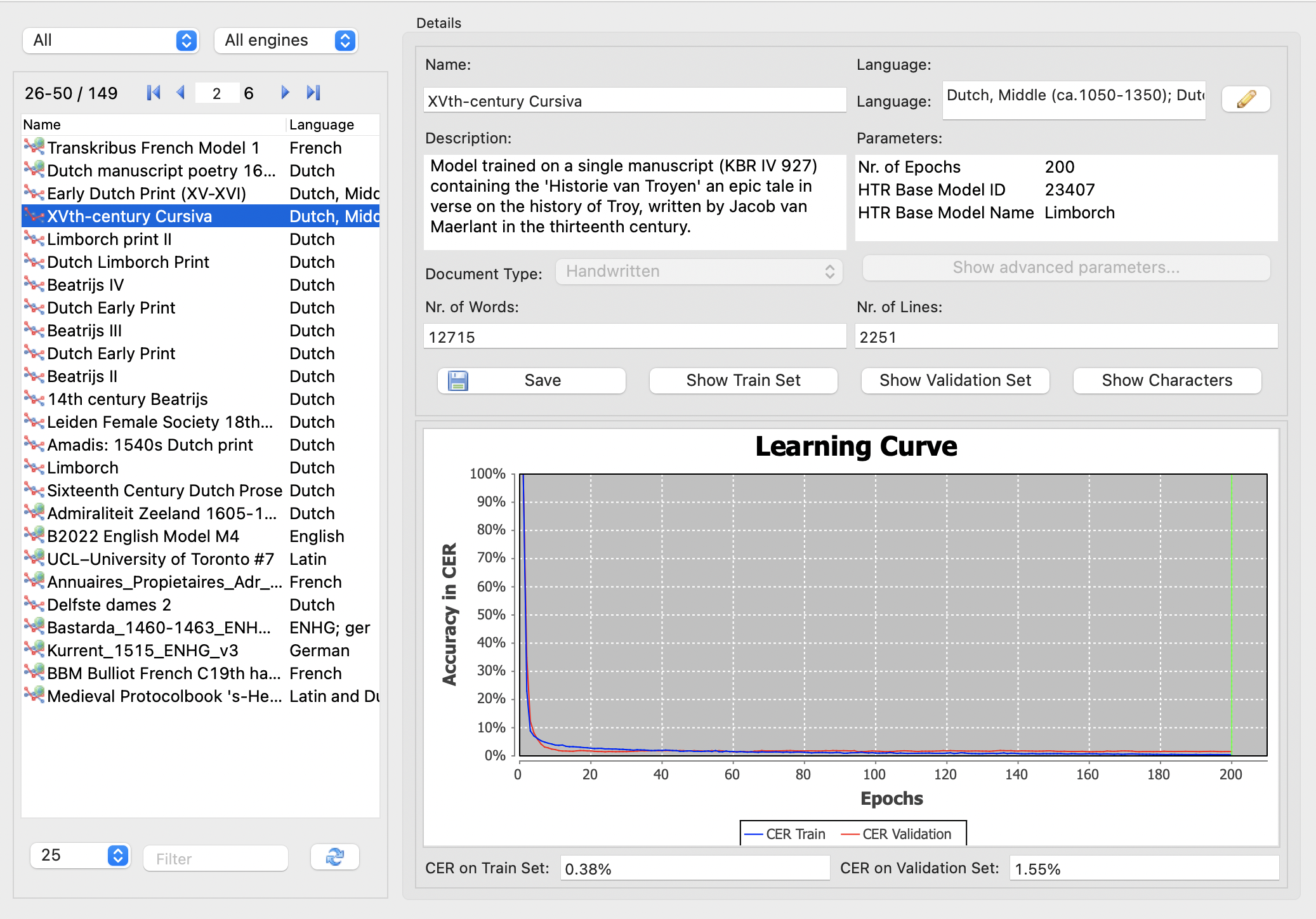

One of the most successful platforms out there for HTR is Transkribus, which has over 80,000 users worldwide. Having started off as a temporary research project funded by the European Union’s ambitious Horizon 2020 scheme, it is now a cooperative company based on institutional membership and partially paid services. It comes in a full-option ‘Expert Client’ (see sample above, fig. 2) or in a ‘Lite’ version (see sample below, fig. 3) that is very easy to navigate. The platform is a splendid example of how modern technology can help answer questions from, and fill gaps in, the humanities. Its thousands of users are working with all kinds of handwritten material – from medieval to modern – in very different languages and scripts. Based on an input of human transcriptions – a few dozen pages will suffice – the computer develops a reading model that can be more precise, and that will certainly be quicker, than handing the transcription work out to humans.

The ‘HTR models’ that Transkribus trains can be either specific to a certain hand in a specific language, or can be used more generally for any handwriting from a period of time. For example, Transkribus can train an HTR model to automatically read the handwriting of a single scribe working on one specific manuscript from the mid-fourteenth century. But it can also combine several of these single ‘models’, or the data underlying them, to develop general reading models that can produce automated text for, say, any handwritten record dating from the fourteenth century. To be fair: the more diverse the material on which the model has been trained, the less accurate the reading model will turn out to be. But the technology is improving rapidly, and institutions are increasingly seeing the value of HTR platforms such as Transkribus to provide easy access to their holdings.

Successful projects

Institutions and scholars in the Netherlands have turned out to be early adopters of Transkribus. To name but one impressive project: the City Archives of Amsterdam are transcribing all of their notarial deeds, spanning the period of 1578 to the present, represented by 3.5 kilometres of archival records. In the ‘Alle Amsterdamse Akten’ project, the impressive goal is to make this material searchable and accessible, through a combination of the HTR technology developed by Transkribus and the volunteer transcription platform of ‘VeleHanden’. The results so far have exceeded expectations. Similar projects have focused not on archival records, but on manuscripts with narrative texts, such as the partly Leiden University-based research project ‘Chronicling Novelty’. Here too, the HTR technology provided easier access to manuscripts that would never have been studied on this scale before.

An educational tool

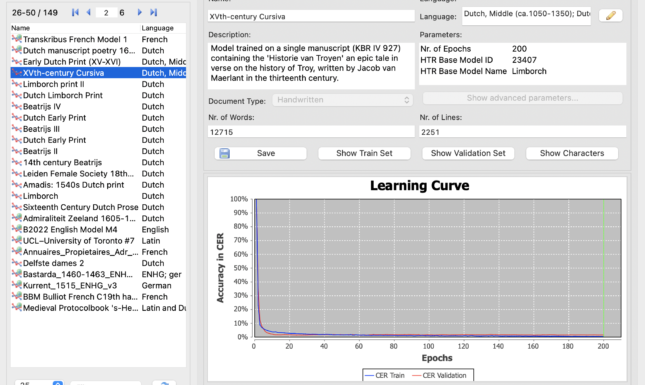

In literary historical scholarship too, there is an increasing interest in the technology. Needless to say, as teachers of the ‘Digital Editing’ class in Leiden’s Dutch Studies curriculum, we saw the potential of including HTR in our classes as an educational tool. In the past three years, students of Dutch literature in Leiden have been introduced to the Transkribus platform. They eagerly took part in producing very precise transcriptions as training material for the computer models, and were astounded at the result of their efforts. With three small groups of 10-20 students, we produced near-perfect reading models of medieval handwritten text in Dutch dating to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (see, for example, fig. 4). Students also worked on printed material, which is of course much more stable than handwritten text, and produced models that can read printed text from the late fifteenth century onwards, with splendid results. The classes ended each year with a mock comparison of the time and precision that the students took in producing their transcriptions, to the pace and accuracy of the model that was trained based on their work.

Much to the students’ surprise, the computer, using a model based on their input, ‘reads’ a page of a medieval manuscript in just under 30 seconds, producing between 1 and 3 mistakes per 100 characters. That is well below the error rate of average students, but it is especially the time difference that is impressive. Depending on their previous experience, students attested that it took them several hours to produce a transcription of a single page. Taking into account the time that went into correcting their work, so as to attain perfect training material, it is undeniable that the HTR technology is a quantum leap forward in processing digital images into machine readable text. The result of an automated reading of course is no text edition in the proper ‘philological’ sense, but it saves a humongous amount of time in the painstaking transcription phase.

However, there is the downside of having to correct all of this computer-generated material. But this process too can produce insights. When going through the automated transcriptions, it is often interesting to see how the mistakes the computer makes differ very much from the mistakes made by students. The automated model, even if it works from a background dictionary that is related to the specific source material, will more likely produce nonsensical readings than the students. The latter, then, tend to be more distracted by the modern spelling of Dutch, and will often unintentionally modernise the Middle Dutch to what they are used to.

Out with the old?

All in all, however, our experiences are undoubtedly positive. Students learn that while the technology can produce impressive results, it relies on their own human precision, and therefore requires them to master the skill of palaeography themselves. At the same time, gaining insight into the processes behind HTR makes the students makes students aware of scientific progress in this technology. Better still, since their HTR models are shared with the scientific community, it makes them proud to realise that their efforts are helping to improve the technology for other scholars.. In our case, three years of eager and interested students’ work has produced models for mid-fourteenth century and mid-fifteenth century Dutch handwriting, and a model for printed text that can be used for other manuscripts and printed books than the ones that we used as training material.

But does the technology have the potential to replace the ‘auxiliary science’ of palaeography altogether? I would say: no. Seen from the point of view of archives and libraries, it does provide an unforeseen opportunity to provide easy access to their collections to a wider audience. And as more models become available to the public, access to HTR technology will become as easy for the old uncle trying to decipher nineteenth-century diaries for the family tree, as it is now for specialised scholars. But the basis of good HTR models remains a critical amount of human input, and transcriptions need to be corrected by someone who knows how to read the source themselves. I hope that universities will continue to train students capable of providing this base material, and judging from the students that we introduced to the topic, their enthusiasm will be no problem.

Links:

Download and find out more about Transkribus here

You can practise your palaeographic skills here!

© Bram Caers and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2022. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Bram Caers and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.