And then Christ turned the children into pigs: A curious miracle in late medieval England

A curious miracle has a young Christ turn Jewish children into pigs. The scene was particularly popular in late medieval England and has a problematic connection to medieval antisemitism.

What happens when you hide your children from Christ in an oven?

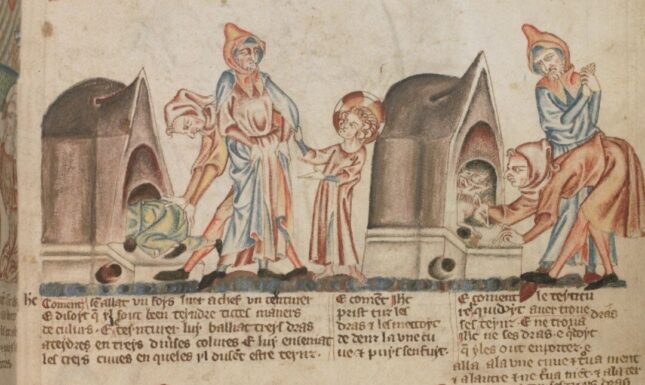

A fourteenth-century English manuscript, known as the ‘Holkham Bible Picture Book’ (c. 1327-1335), contains evocative illustrations of various biblical and apocryphal scenes. One of these scenes shows how a young Jesus Christ turned children into pigs. On fol. 16r, the Holkham artist depicts a man pushing a crawling figure into an oven, while another man is addressed by a young Jesus Christ (recognisable by his cruciform halo); in a subsequent scene, we see the same oven but now it is filled with three little pigs. The two men look on with dismayed expressions on their faces; Christ is gone.

This illustration depicts ‘The Miracle of the Children in the Oven’, an apocryphal legend that belongs to a series of stories associated with the infancy of Christ. In the accompanying text, we learn that Christ wanted to play with some Jewish children but that their parents wanted to prevent this by hiding their kids in the oven. When Christ asked the parents what was in the oven, the parents replied that it was filled with pigs. ‘So be it’, Christ said and, when Christ had gone and the parents wanted to check on their children, the oven was filled with pigs.

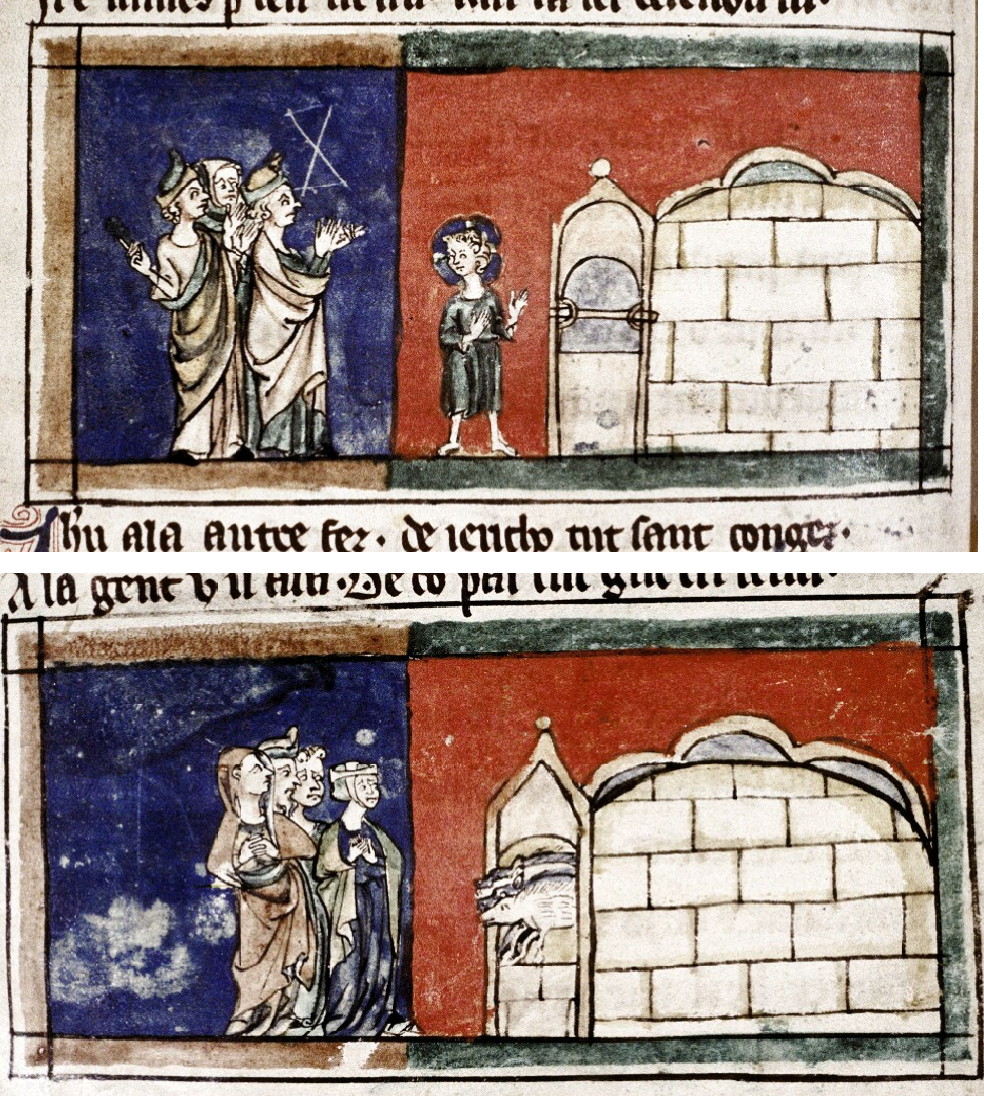

The illustrations in the Holkham Bible Picture Book is one of five extant medieval pictorial representations of this miracle. The fact that these images all have an English origin suggests that the legend was particularly popular in medieval England, even though the story itself may have originated in an early medieval Arabic text (where the children are turned into goats, see Smith 2003: 275-280). A second depiction survives as a full-page miniature on a manuscript leaf from a fourteenth-century Psalter, where four worried bearded men look at an oven. Staring back at them are six pigs, with somewhat comically disgruntled expressions on their faces. A third partial representation of the legend is found as part of the so-called ‘Tring tiles’, a set of decorated tiles from c. 1330, which depict various scenes of Christ’s youth, including a teacher slapping Jesus at school and the story of the boy that jumped on Jesus’s shoulder (and died as a result). On one tile, three men point at an oven that presumably has the children-soon-to-be-turned-into-piglets in it; the tile that would have shown the piggy-reveal has sadly been lost.

Adding a woman’s emotional response

Two further depictions of the ‘Miracle of the Children in the Oven’ stand out for their inclusion of a female figure in the scene. The first is found in the lavishly illustrated manuscript version of the Anglo-Norman text Les Enfaunces de Jesu Crist: Bodleian Library, MS. Selden Supra 38 (which may have shared a common model with the Tring tiles; see Casey 2007).

While the other depictions described above only appear to feature male parents, the artist of Selden Supra 38 added a female figure at the bottom scene where the porcine transformation is revealed. She holds her hands folded in front of her heart with a sorrowful expression, possibly emphasizing the emotional response of parents seeing their children turned into pigs.

The last depiction of the Miracle of the Children in the Oven has an even more striking addition of a female figure. This depiction is found in yet another 14th century-manuscript from England: a Book of Hours known as the ‘Neville of Hornby Hours’. Here the artist has depicted the scene within a historiated initial D. The picture shows the now familiar scene of pigs sticking their heads out of an oven amid a crowd of surprised individuals.

What is striking is the addition of a young female figure outside of the initial D that has her hands raised to her head in what looks like a state of emotional distress. It has been suggested that this woman represents the young daughter or granddaughter of the owner of the book, Isabel de Byron, and that the latter may have used her beautifully illuminated Book of Hours for religious instruction (Bartal 2016: 62). The figure shows the appropriate emotional response to this scene: ‘Oh no! That’s what you get when you don’t allow your children to interact with Christ!’

The Miracle of the Children in the Oven and medieval antisemitism

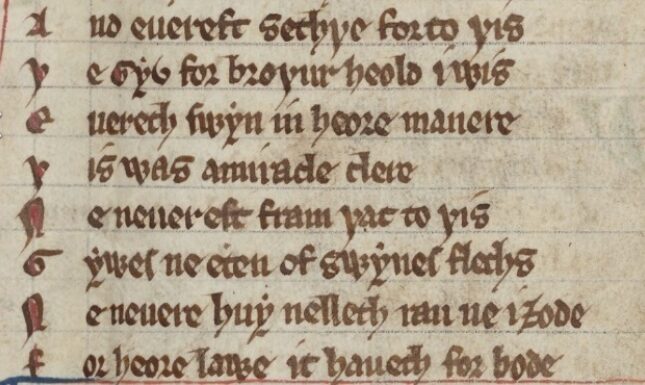

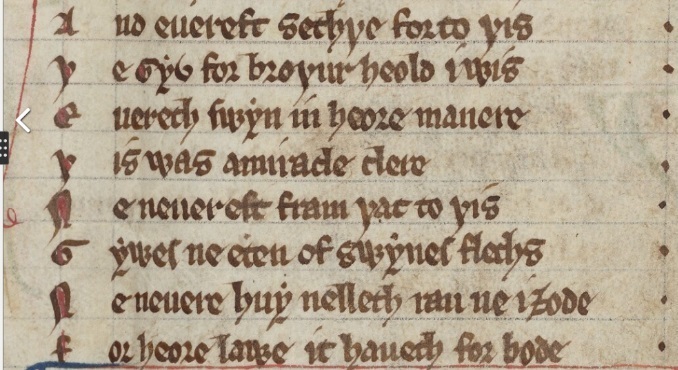

Given my own particular interest in medieval swine (as reflected in the ‘hog blogs’ published as part of the Leiden Medievalists Blog), I was particularly attracted to this medieval legend for its inclusion of these animals and the somewhat silly idea of an annoyed Christ turning reluctant playmates into pigs. I was dismayed to learn, however, that the Miracle of the Children in the Oven had a far more disturbing appeal to those living in fourteenth-century England: rampant antisemitism. As Mo Pareles (2019) has shown, textual variations of this miracle found fertile ground in late medieval England because it allowed people to link Jews to pigs and help explain one of their distinctive traits, the prohibition of the pork. In the Middle English versified Apocryphal History of the Infancy (found in a late thirteenth-century manuscript without illustrations), for instance, the story of the porcine transformation of the children is explicitly linked to the fact that Jews do not eat pig-meat:

And euereft sethþe for to þis

Þe Gyv for broþur heold i wis

Euerech swyn in heore manere

Þis was miracle clere

Ne neuer eft fram þat to þis

Gywes ne eten of swynes flechs

Ne neuere huy nelleth rau ne izode

For heore lawe it haueth for bode

And ever since, because of this,

the Jew, I know, considers as a brother

every swine according to their custom

This was an evident miracle.

Never again from that moment to this

have Jews eaten of the flesh of a pig

nor do they ever want, raw or roasted,

because their law has forbidden it.

By explicitly relating Jews to pigs, the story of the Miracle of the Children in the Oven participates in a long and troubling discourse that sought to dehumanize Jews by linking them to unclean animals that symbolised such sins as lechery (Pareles 2019: 228-231). In this, the late medieval depictions of the miracle of the children in the oven may be similar to the infamous and troubling medieval ‘Judensau’, where Jews are shown suckling from a pig – a pictorial tradition that started in 13th-century Germany and remained popular until the 19th century (Shachar 1974).

On that sobering note I will end this blog post: while medieval swine remain a fascinating topic for light-hearted blog posts about the Middle Ages, we should not close our eyes to the nefarious purposes for which elements of medieval culture (its porcine parts included) have been put to use, both in the Middle Ages and beyond.

Bibliography

- Bartal, Renana. Gender, Piety, and Production in Fourteenth-Century English Apocalypse Manuscripts (Abingdon, 2016)

- Casey, Mary F. “The Fourteenth-Century Tring Tiles: A Fresh Look at their Origin and the Hebraic Aspects of the Child Jesus’ Actions.” Peregrinationes 2.2 (2007): 1–53.

- Pareles, Mo, "Already/Never: Jewish-Porcine Conversion in the Middle English Children of the Oven Miracle', Philological Quarterly 98.3 (2019): 221-242.

- Shachar, Isaiah. The Judensau: A Medieval Anti-Jewish Motif and Its History (London, 1974)

- Smith, Kathryn A. Art, Identity and Devotion in Fourteenth-century England. Three Women and Their Books of Hours (London, 2003)

© Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2022. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thijs Porck and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.