Alfred the Great as Europe’s Darling: The Afterlives of an Early Medieval King in 19th-century Europe

In Victorian England, King Alfred (c. 849-899) became a nationalist symbol, heralded as ‘England’s Darling’. Yet, the popularity of this early medieval English king extended beyond England’s borders, well into continental Europe, where Alfred inspired authors and historians as ‘Europe’s Darling’.

King Alfred (c. 849-899) became king of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom Wessex in 871. He was successful as a military leader during Viking invasions plaguing England, which ultimately led to the political unification of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, including Mercia, making Alfred the first ‘English’ king. In addition, he was responsible for a cultural revival, which included a translation programme of texts translated from Latin into Old English with prefaces claiming the king as the author of these texts. In this blogpost, I will discuss Alfred’s importance in 19th-century Victorian England, as well his popularity in continental Europe. After this, I will discuss the first professional biography of Alfred’s life, made by the German scholar Reinhold Pauli, and explain the lure of King Alfred for a German historian in the middle of the 19th century.

Alfred as England’s Darling: Alfred the Great and the Victorians

It could be said that Victorian England was obsessed with King Alfred the Great. The groundwork for this popularity was laid in the eighteenth century, which saw the emergence of King Alfred as a perfect example of a medieval king. This image leads to an “apotheosis” during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901), when King Alfred’s role in English history was expanded to include him as the founder of the Royal Navy, the British Empire, “the father of English prose, and as the archetype of all hero qualities” (Keynes 1999, 333). As such, King Alfred was cast in a wide variety of roles, ranging from military hero to literary mastermind. While these claims are exaggerated (King Alfred did not, for example, found the Navy), they show the Victorian interest in Alfred as a foundational figure for a national mythology.

Alfred’s popularity made him a staple figure in Victorian popular culture. In 1845, King Alfred was one of the few monarchs approved as subject matter for paintings in the New Houses of Parliament (Keynes 1999, 337). Alfred Austin (1835 – 1913) was appointed poet laureate in 1896, the same year he published England’s Darling, a drama set in medieval England with Alfred the Great as its main character. In this work, Alfred serves as an exemplary figure, whose ‘English’ qualities should be revered, as well as emulated (Arnott 2015, 182-4). Austin especially celebrates Alfred for his unification of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, which created an “early English empire” (185). On a more local level, the English town Wantage proudly celebrated their famous son (King Alfred was born in Wantage) with a statue in its market place, which was unveiled in 1877 (Keynes 1999, 346). The statue is shown in Figure 2 and illustrates the dual nature of King Alfred: he is holding both a scroll and axe as a symbol of his military prowess and interest in learning.

The Victorian fascination culminated with a big celebration of the millennium of King Alfred’s death in October of 1901 (two years too late, because Alfred died in 899), which included a variety of activities, ranging from a commemorative exhibition to a poem by poet laureate Alfred Austin. For the Victorians, Alfred was a foundational figure of English history, whose qualities were praised by poets as an exemplary Englishman.

Alfred in Europe: Ballets, Operas and Poems

In the 19th century, King Alfred’s popularity spread beyond Victorian England: he was also celebrated in various publications across continental Europe.

In the Netherlands, for instance, Johannes M. Schrant published Lofrede op Alfred den Groote [Eulogy of Alfred the Great] (1845). The eulogy describes Alfred as a ruler, “wiens weêrga men noch bij de oude, noch bij de latere Volken ontmoet” [whose equal people have seen neither among the earlier, nor among the later peoples] (Schrant 1845, 53). For Schrant, Alfred was the epitome of rulership and any people lucky enough to have their own Alfred would be very fortunate (54).

The figure of King Alfred also inspired the famous Czech composer Antonín Dvořák (1841 – 1904), who composed an opera about Alfred in three acts in 1870 (coincidentally, this was also his first opera). The opera was titled simply Alfred and was written in German with a libretto by Karl Theodor Körner. The story of the opera focuses on Alfred infiltrating the Danish camp disguised as a minstrel, a story first found in the 12th-century chronicle Gesta regum by William of Malmesbury (Keynes 1999, 230). Dvořák’s opera is a romanticized retelling of the tale: in the original medieval story, Alfred wants to learn of the enemy’s plan, but here Alfred is motivated by the fact that his betrothed Alvina has been taken captive by the Vikings. The opera has a happy ending: the British army, led by Alfred, successfully attacks the Danish camp and he reunites with Alvina. Interestingly, Dvořák never really acknowledged the existence of this opera, possibly due to strong Czech nationalist sentiments at the time of writing it, because the opera was written in German (Beveridge 1996, 287).

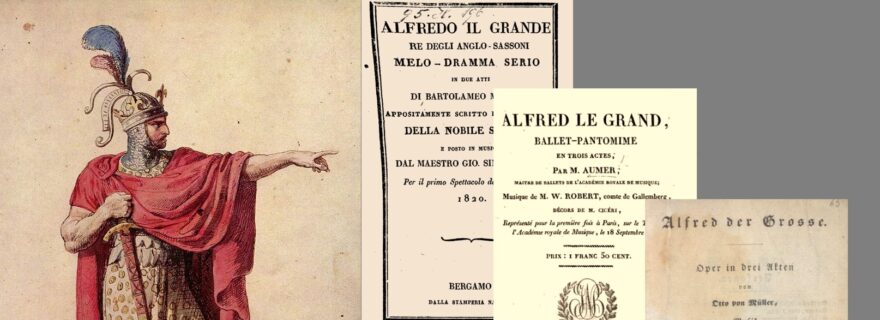

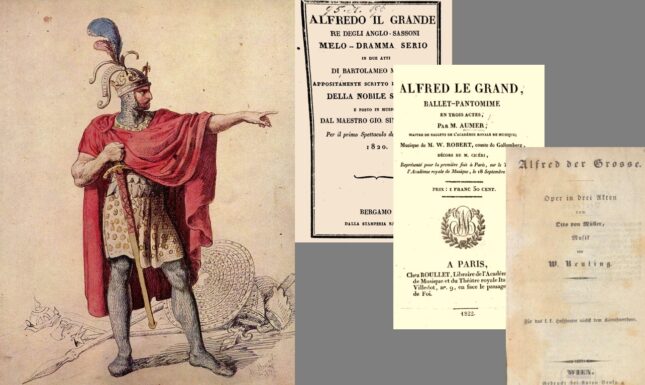

Interest in King Alfred also crossed language borders through translations of popular works about him. For example, the Austrian composer Wenzel Robert von Gallenberg’s ballet Alfred der Grosse (1820) was translated into French as Alfred le Grand, Ballet-pantomime en trois actes. This French translation premiered on September 18, 1822 in Paris. A popular, German biography of Alfred titled Leben Alfreds des Grossen was published by Friedrich Lepold Graf zu Stolberg-Stolberg in 1815; its French translation under the title Histoire du Roi Alfred-le-Frand par le comte de Stollberg. Traduit de l’allemand saw its third revised and corrected edition in 1838, indicating a high demand for the title and Alfred's life across non-Anglophone Europe.

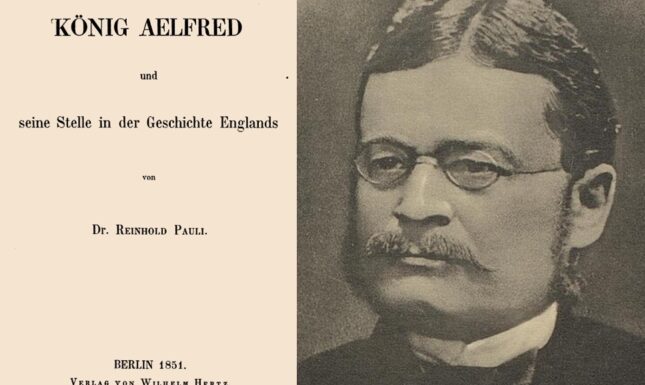

Alfred for the Germans: Reinhold Pauli, Alfred and the German Revolution of 1848

Continental interest in Alfred extended beyond the medium of poems, operas and ballets; he also became a subject of historical research for continental scholars. The first ‘modern’ biography of King Alfred was written in German by Dr. Reinhold Pauli (Keynes 1999, 341). His biography of Alfred is titled König Aelfred und seine Stelle in der Geschichte Englands [King Alfred and his Place in the History of England], was published in 1851; two years later, it was translated into English by Benjamin Thorpe under the title The Life of Alfred the Great.

In the introduction to his biography of Alfred, Pauli describes that he started writing his work in November 1848 and that contemporary events in German politics motivated him to do so:

Der Plan zu der nachfolgenden Arbeit wurde zu Oxford im November des inhaltschweren Jahres 1848 entworfen, zu einer Zeit, da deutsche Herzen wie selten zuvor für die Erhaltung des Vaterlandes und insbesondere für das Fortbestehen desjenigen Staats erzitterten, den der Himmzel zum Schutz und Hort Deutschlands bestimmts hat. Es waren schreckliche Novembertage. (Pauli 1851, v)

[The plan for the following work came to be in Oxford in November of the content-heavy year 1848, at a time, when German hearts as rarely before for the preservation of the fatherland and in particular for the continued presence of that state, that heaven has appointed as the protector and refuge of Germany. Those were terrible November days.]

For Pauli, November 1848 represented a period of “schreckliche Novembertage” [terrible November days] (Pauli 1851, v). This is hardly surprising, November 1848 was a turbulent period in German history: this month saw the assassination of democratic revolutionary Robert Blum and the forced expulsion of the Prussian National Assembly by King Frederick William IV of Prussia, both pivotal events in the German revolutions of 1848–1849.

Reinhold Pauli was a proud Prussian nationalist and royalist, who had worked for the Prussian ambassador, Baron von Bunsen, as the latter’s private secretary in London since 1847. His wife Elisabeth describes in a posthumous biography of her husband that his father had instilled in him a love for Prussia (Elisabeth Pauli 1895, 11). In some of his private letters, Pauli shows his support for the King of Prussia in these trying times: “Despite all the unrest, I think all day long, as a good Prussian, of the King […] May God bless him and prove him right before the whole unbelieving world.” (Reinhold Pauli to his cousin, 15-10-1849; edited in Elisabeth Pauli 1895, 136).

In his biography of Alfred, Pauli makes a direct connection between King Alfred’s England and Prussia. He writes that an empire can be threatened by foreign invaders with help coming from a remote place: whereas Alfred came to the aid of the people in Somerset, people from the easter border of Prussia came to the aid of the Germans after Napoleon’s army had invaded (Pauli 1851, p. 127). By comparing Prussia to Alfred’s England, Pauli may have been making the case for the King of Prussia as a new Alfred for all of Germany, someone who might unify the nation during its current time of unrest.

Bibliography

- Akademie klasické hudby, z. ú. transl. by Karolina Hughes. “Alfred, B16.” <https://www.antonin-dvorak.cz/...;. Accessed on 24 May 2025.

- Anlezark, Daniel. Alfred the Great (Arc Humanities Press, 2017).

- Arnott, Megan. “Alfred the Little: Medievalism, Politics, and the Poet Laureate.” In Medievalism on the Margins edited by Karl Fugelso with Vincent Ferré and Alicia C. Montoya (Boydell and Brewer, 2015), pp. 177-192.

- Aumer, Jean-Lous. Alfred le Grand, Ballet-pantomime en trois actes; Musique de W. Robert, comte de Gallemberg (J-N. Barba, Libraire, 1822).

- Beveridge, Davir R. Rethinking Dvořák: Views from Five Countries (Clarendon Press, 1996).

- De Stollberg. Histoire du Roi Alfred-le-Grand third revised and corrected edition (La Société Nationale, pour la Propagations des bons Livres, 1838).

- Kalmar, Tomás Mario. King Alfred the Great, his Hagiographers and his Cult (Amsterdam University Press, 2023).

- Keynes, Simon. “The Cult of King Alfred the Great.” Anglo-Saxon England 28 (1999), pp. 225-356.

- Körner, Karl Theodor. “Alfred der Große: Oper in zwei Aufzügen.” In Theodor Körner’s Sämmtliche Werke (Carl Gerold, 1835), pp. 309-321.

- Parker, Joanne. ’England’s Darling’: The Victorian Cult of Alfred the Great (Manchester University Press, 2017).

- Pauli, Reinhold. König Aelfred und seine Stelle in der Geschichte Englands (Verlag von Wilhelm Hertz, 1851).

- ——. The Life of Alfred the Great translated from the German of Dr. R. Pauli in which is appended Alfred’s Anglo-Saxon Version of Orosius with a literal English Translation, and an Anglo-Saxon Alphabet and Glossary, transl. by B. Thorpe (Henry G. Bohn, 1853).

- Pauli, Elisabeth. Reinhold Pauli: Lebenserinnerungen nach Briefen und Tagebüchern zusammengestellt (Ehrhardt Karras, 1895).

- Schrant, J.M. Lofrede op Alfred den Groote (J.J. Thyssens en Zoon, 1845).

- Tottola, Andrea Leone and Gaetano Donizetti. Alfredo il Grande: Drama per Musica da Rappresentarsi nel real Teatro S. Carlo (Dalla Tipografia Flautina, 1823).

- Vick, Brian E. Defining Germany: The 1848 Frankfurt Parliamentarians and National Identity (Harvard University Press, 2002).

This blog post was produced during a P. J. Cosijn Research Fellowship, which is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program (EMERGENCE, Grant agreement No.101115867, https://doi.org/10.3030/101115867 ). Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them

© Adrie Huijbrechts and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Adrie Huijbrechts and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.