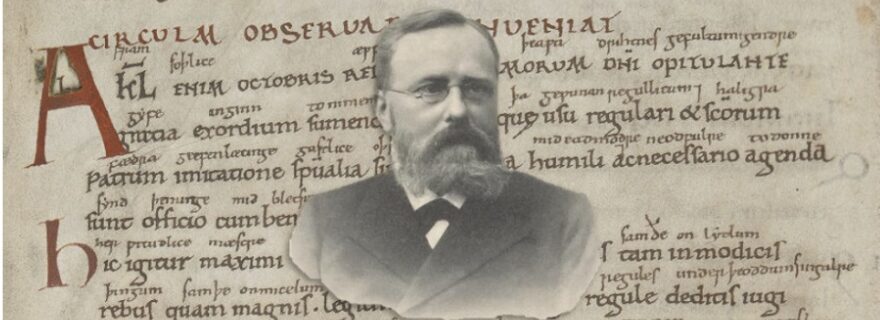

A forgotten Dutch medievalist? Tracing the influence of Cornelis Stoffel (1845–1908) in Old and Middle English studies

Not all academic work leaves its mark in bibliographies. Looking for traces of other kinds of scholarly engagement can broaden our understanding of our field and the people who have contributed to it.

The nineteenth century saw huge advances in making medieval English accessible to a general audience. From the obscure pursuit of a handful of independent (and typically independently wealthy) scholars, by the closing decades of the century it had become not only a defined and professionalised field of study at university level, but also a foundational element of English curricula both in the United Kingdom and further afield. The somewhat unsystematic scholarship of earlier generations had given way to the orderly grammars, glossaries and editions. Many of these are still consulted by scholars today.

One particularly successful publication of this period was Henry Sweet’s An Anglo-Saxon Primer. Appearing in eight editions between 1882 and 1896 (with a ninth edition revised by Norman Davis published in 1953), it contained an introductory grammar and a selection of simplified Old English prose texts, accompanied by notes and a glossary. The Primer was billed in the author’s preface to the first edition as ‘the easiest possible introduction to the study of Old English’ and was clearly designed for classroom use.

Sweet’s role in advancing and popularising the study of Old English in the nineteenth century is well known today (see, e.g., the blog post Henry Sweet: The Man Who Taught the World Old English), but his work could not have been achieved alone. The preface to the third edition of his Primer offers us a glimpse behind the scenes; Sweet acknowledges ‘the suggestions and corrections kindly sent to me by various teachers and students who have used this book, among whom my especial thanks are due to the Rev. W.F. Moulton, of Cambridge, and Mr. C. Stoffel, of Amsterdam.’

The life and interests of William Fiddian Moulton (1835–1898), the first of the two users singled out for especial thanks, are what we might expect for a user of Sweet’s textbook: a university-educated biblical scholar and the first headmaster of The Leys School, Cambridge. The second. Mr. C. Stoffel of Amsterdam, is perhaps a little less expected, but an investigation into his life and work has a lot to tell us about medieval scholarship in the late nineteenth century.

Stoffel as Anglicist

Cornelis Stoffel, the eldest son of a timber merchant, was born in Deventer in 1845. He was recognised as a child for his academic and linguistic abilities, and studied at a gymnasium. At the age of 21 he began to work as a teacher of English at the Hogere Burgerschool in Utrecht; a few years later, he would move to the Openbare Handelsschool in Amsterdam. It must have been during Stoffel’s teaching career that he came across Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Primer, although it is not clear whether he used it with his students or simply studied from it himself. Alongside his teaching, Stoffel was clearly pursuing many of his own projects. His student edition of William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, published in 1869, maintains a clear connection to the classroom, but during his teaching career we can also see the early development of the interest for which he would later become well-known in the Netherlands, namely the academic study of present-day English. In particular, he is known to have been an early contributor to the Oxford English Dictionary, sending in more than 2,000 quotations.

Teaching would be his career until 1887 when his poor health forced him to retire. With the additional time now available to him, Stoffel seems to have turned in earnest to research and writing. He made pioneering contributions to the study of contemporary English language and literature in the Netherlands, including his Studies in English, Written and Spoken, for the Use of Continental Students (1894) and his Intensives and Down-toners: A Study in English Adverbs (1901). Obituaries of Stoffel focus on his academic contributions to Modern English lexicography and linguistics, as well as his interpretations of such literary authors as William Shakespare, Jane Austen and Charles Dickens (e.g., Bunt; Posthumus). His interest in medieval English has, however, received less attention (although it is perhaps not a coincidence that Intensives and Down-toners was the first volume in the series Anglistische Forschungen, which was edited by the German Johannes Hoops, an expert on Old English who would go on to publish a number of monographs on Old English topics in the same series).

Stoffel as Medievalist

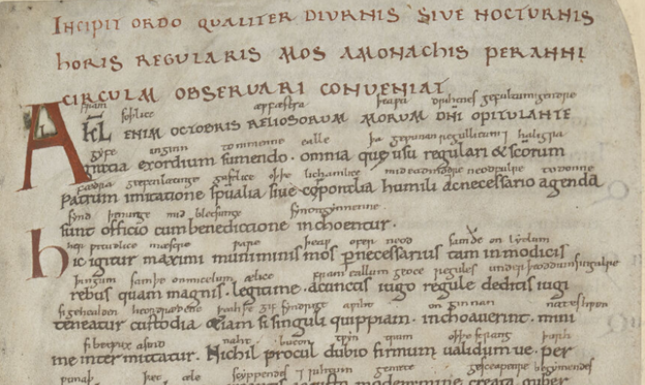

Even from Stoffel’s published work, his interest in medieval texts is clear; several essays in his Studies in English are devoted to tracing the historical development of words like for and no from Old English to Stoffel’s time. However, it is in his contributions to the publications of others that his medieval interests become most apparent. The Dutch scholar Henri Logeman, in his 1888 edition of The Rule of S. Benet (a bilingual Old English-Latin handbook for monastic life), acknowledges in the notes (p. 120) ‘a correspondence… with Mr. C. Stoffel, of Nymegen, the results of whose extensive reading are always so kindly placed at the disposal of his correspondents.’

These correspondents were apparently both numerous and international; Henry Sweet thanks Stoffel not only in his Anglo-Saxon Primer but also in the second edition of his First Middle English Primer (1891). Several emendations listed in the errata to Walter Skeat’s The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer (1894, pp. 400–409) are credited to Stoffel. Both Sweet and Skeat were English, but Stoffel’s networks were wider still; the Danish linguist Otto Jespersen acknowledges a personal communication from Stoffel in his Progress in Language (1894, p. 191),

Stoffel’s correspondence on medieval topics must have been far more copious than is reflected in published acknowledgments. A brief glimpse at this correspondence can be found in the archives of Kings College, London (K/PP144/1 Skeat 1/13). In 1883, the English philologist Richard Morris (1833–1894) received a letter from Stoffel about Part I of the new edition his Specimens of Early English, which had been published the previous year. The preparation of this volume had been a long and difficult task for Morris, with Part I being published a decade after Part II. Stoffel evidently recognised some of the signs of this struggle, and was not afraid to offer his criticism: ‘I hope you will excuse my volunteering an opinion that this book is less carefully edited than Part II.’ Nearly nine densely-written pages of corrections and queries follow, in which Stoffel, despite having no access to the manuscripts of the Middle English texts that Morris prints, confidently offers his own interpretations and shows a familiarity with important scholars of Old and Middle English including Eduard Mätzner, Joseph Bosworth and Christian Grein. (A second, fragmentary letter from Stoffel is preserved in the same collection; the addressee is unclear, but may be Morris again.)

Stoffel concludes his letter by expressing his admiration for the work of the Early English Text Society and enquires whether it would be possible for him to become a member. The Early English Text Society, which was founded in 1864 and dedicated to publishing previously inaccessible medieval English texts, may have been of particular interest to Stoffel because of its close relationship with the Oxford English Dictionary, for which he had in his earlier years supplied quotations, but it was in any case the most realistic way for him to read the medieval texts that so fascinated him. Stoffel’s keen editorial eye and linguistic knowledge enabled him to offer useful feedback even at a distance, but his ability to participate fully in this kind of philological work was nevertheless limited by his inability to consult manuscripts – and, if not manuscripts, at least reliable editions of medieval texts. As he wrote somewhat mournfully to Morris, ‘I begin more and more to feel the want of complete texts’.

Stoffel and Scholarship

So, what can we learn from this glimpse at Stoffel’s life about the study of medieval English in the late nineteenth century? Stoffel’s impact on Old and Middle English scholarship may have been modest, but his presence in the scholarly record serves as a useful warning against over-simplifying our account of how the field developed. Even as English philology became more professionalised in the nineteenth century, significant contributions to the discipline could still be made by scholars who did not hold a university position. Indeed, Henry Sweet himself, with whose Primer I began this blog post, only obtained a university post in 1901, and published his most important work on medieval topics while unaffiliated to a university; Stoffel, meanwhile, never attended university at all, although a few years before his death he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Groningen.

Even more significantly, perhaps, Stoffel reminds us that not all scholarship takes the form of independently written monographs or articles. To fully appreciate the work of Stoffel and the many other scholars whose expertise was not shared in the form of traditional publications, we need to look beyond the obvious sources and piece together evidence from across a person’s life. What is more, Stoffel’s medieval studies show that and that research at its best has always been a collaborative process that relies on the sharing of knowledge – something that is as true now as it was in his day.

References:

- Blok, P.J. & P.C. Molhuysen (1912). ‘Stoffel, Cornelis’ in Nieuw Nederlandsch biografisch woordenbook, vol. 2.

- Bunt, G.H.V. (1964). ‘Dr. C. Stoffel, pionier der Nederlandse anglistiek’. Levende Talen 224, pp. 214–221.

- Jespersen, Otto (1894). Progress in Language, with Special Reference to English. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

- Logeman, Henri (1888). The Rule of St Benet, Latin and Anglo-Saxon Interlinear Version. London/Utrecht: Trübner & Co./J.L. Beijers.

- MacMahon, M.K.C. (2006). ‘Sweet, Henry’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/36385>

- Norgate, G. Le G. & Joanna Hawke (2004). ‘Moulton, William Fiddian’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/19432>

- Pak-Meijer, Hanna (2009). ‘Cornelis Stoffel, een pionier in de academische beoefening van de Engelse taal- en letterkunde in Nederland’. e-Meesterwerk 5. <https://ivdnt.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/e-meesterwerk_05_HannaPak-Meijer_CornelisStoffel.pdf>

- Posthumus, Jan (2014). ‘Cornelis Stoffels bijdragen aan de tweetalige lexicografie’. Trefwoord. < https://ivdnt.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Stoffel_Trefwoord_def.pdf>

- Skeat, Walter W. (1894). The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer. Volume 6: ‘Introduction, Glossary, and Indexes’. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Stoffel, Cornelis (1894). Studies in English, Written and Spoken, for the Use of Continental Students. Zutphen: W.J. Thieme & Co.

- Stoffel, Cornelis (1901). Intensives and Down-toners: A Study in English Adverbs. Heidelbeg: Carl Winter’s Universitätsbuchhandlung.

- Swaen, A.E.H. (1910). ‘Levensbericht van C. Stoffel’. Jaarboek van de Maatschappij der Nederlandse Letterkunde, 1910, pp. 169–187. <https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_jaa003191001_01/_jaa003191001_01_0021.php>

- Sweet, Henry (1886). An Anglo-Saxon Primer, with Grammar, Notes, and Glossary. Third edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Sweet, Henry (1891). First Middle English Primer: Extracts from the Ancren Riwle and Ormulum with Grammar, Notes, and Glossary. Second edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

This blog post is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program (EMERGENCE, Grant agreement No.101115867, https://doi.org/10.3030/101115867 ). Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

© Rachel Fletcher and Leiden Medievalists Blog, 2025. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Rachel Fletcher and Leiden Medievalists Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.